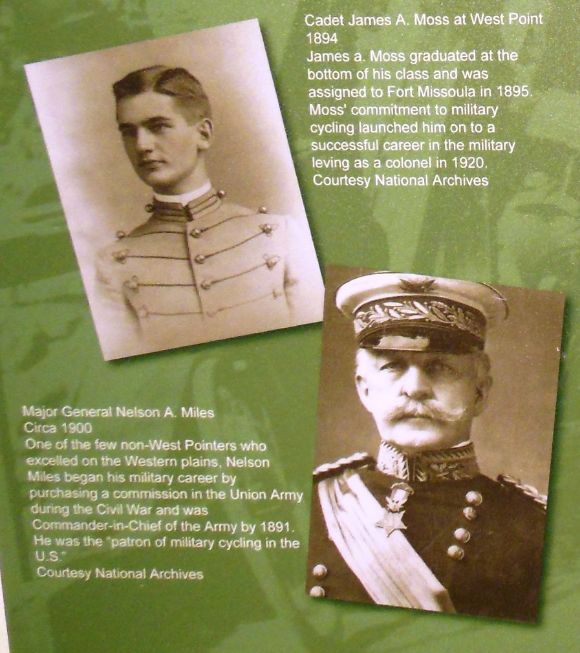

Bicycles started to become popular toward the end of the nineteenth century. In 1892, the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Major General Nelson A. Miles, recommended that a full regiment be equipped with bicycles. The first bicycle corps was organized in 1892 when 2nd Lieutenant James A. Moss received permission to organize the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps.

It should be noted that while some of the Army’s generals championed “the wheel,” there were others who felt that the idea of transporting soldiers by any means other than the horse was a break with an important tradition regarding the eternal bond between a soldier and his horse. Many felt that testing the bicycle as a military device was frivolous and a waste of money.

2nd Lieutenant James A. Moss:

James Albert Moss was born in Louisiana and studied at the University of Louisiana. He then went to the Military Academy at West Point where he graduated at the bottom of his class in 1894. Since he graduated last, he was given an assignment that no one else wanted: he was assigned to the black 25th Infantry Regiment in the rather remote post of Fort Missoula in western Montana.

An avid cyclist, Moss became enamored with the idea of demonstrating that the bicycle had military applications. He officially requested permission to form a bicycle corps. His request moved smoothly through channels and landed on the desk of General Nelson Miles. Miles was already aware of the military potential of the bicycle so he approved the request.

Lt. Moss would later write:

“Not many years ago the bicycle was looked upon as a mere toy, a kind of ‘Dandy horse,” and the riders were considered as fit subjects for pity. This time, however, is a thing of the past; the bicycle of today is a very important factor in our social and commercial life, and bids fair to figure conspicuously in the warfare of the future.”

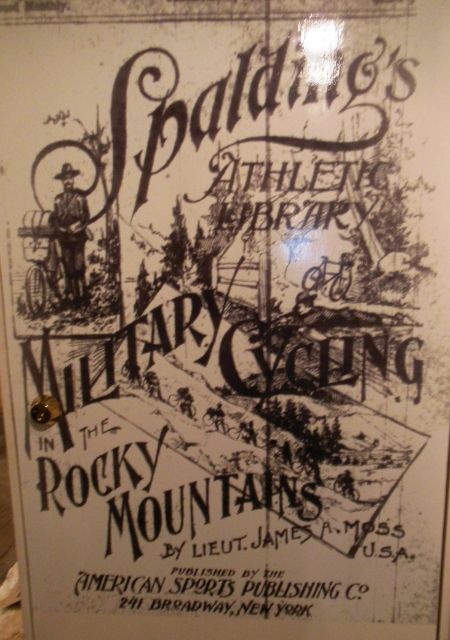

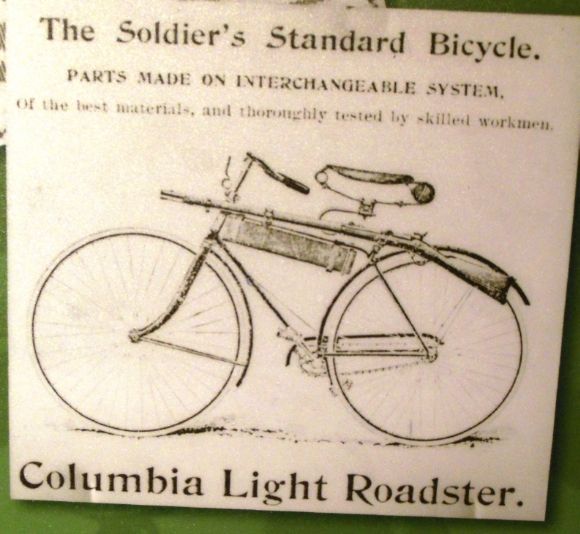

Moss contacted the A.G. Spalding Company, who agreed to provide military bicycles co-designed by Moss at no cost. Part of the stipulation for experimenting with the bicycles was that Moss had to obtain them at no cost as the Army didn’t want to waste money on an untried machine.

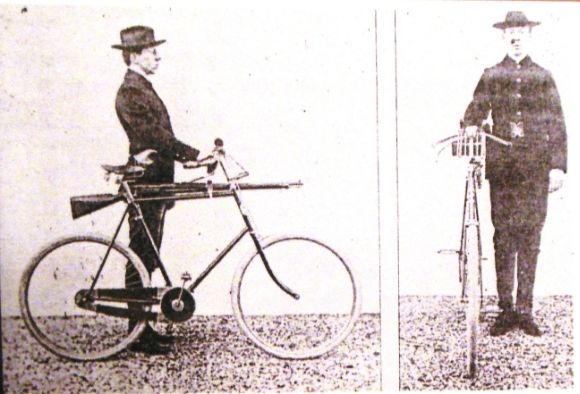

Shown above is one of the military bicycles.

The Bicycle Corps:

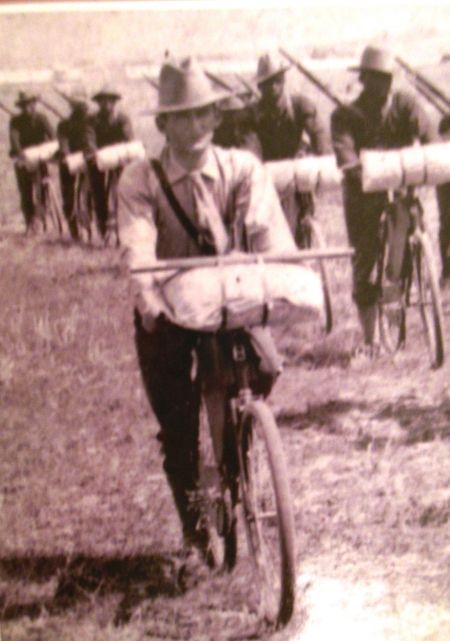

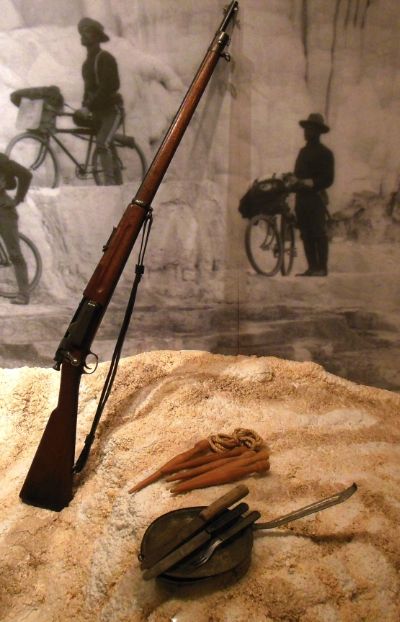

The new Bicycle Corps consisted of Lt. Moss and eight black enlisted men. The men were able to ride in formation, drill, scale fences up to nine feet high, ford streams, and pedal 40 miles a day. Each bicycle carried a knapsack, blanket roll, and a shelter half strapped to the handlebar. A hard leather frame case fit into the diamond of each bicycle. A drinking cup was kept in a cloth sack under the seat. Each rider carried a rifle and 50 rounds of ammunition. Initially, the riders carried the rifles slung over the back and later the rifles were strapped to the horizontal bar on the bicycle. Each soldier carried about 76 pounds of gear.

Shown above is some of the equipment carried by each soldier.

The newly formed bicycle corps was given training in basic bicycle riding and in maintenance. Private John Findley had been a bicycle mechanic prior to his enlistment and provided the troops with instruction on bicycle maintenance and repairs.

With regard to their training Lt. Moss reported:

“The weather permitting, we made daily rides from 15 to 40 miles. After a little practice, the corps attained great proficiency in getting over fences and fording streams.”

Like other military units, they also drilled. In fact, Lt. Moss and 20 soldiers from the 25th Infantry had performed precision bicycle drills at the Missoula, Montana 4th of July celebrations in 1895, prior to the formation of the bicycle corps. A number of cycling drill books were available at this time and Lt. Moss modified the guidelines set forth in

Cyclists’ Drill Regulations by Lt. W. T. May. Many of the cycling drill procedures described in the manuals were found to be impractical. While they looked good on paper, they were difficult—sometimes impossible—to actually carry out with a group of soldiers riding bicycles.

The military cycling maneuvers, trumpet calls, and whistle signals were mostly borrowed from cavalry drills and calls. One of the men included in the newly formed Bicycle Corps was a musician.

One of the drills involved getting over a nine-foot fence. Working in pairs, the soldiers could scale the fence in 20 seconds: this included themselves over the fence, their bicycles over the fence, and their equipment.

The Lake McDonald Trip:

After two weeks of training, the Bicycle Corps made their first long trip: from Fort Missoula to McDonald Lake in the Mission Mountains on the Flathead Indian Reservation. Following rutted dirt roads, the trip took four days. They travelled up steep mountain grades, forded streams, and were often stopped by fallen trees. The return trip was made in rain and the men had to stop from time to time to remove mud from their equipment. In some places they avoided the poor roads by using the railroad tracks. They traveled a total of 126 miles in adverse conditions.

Lt. Moss would later describe McDonald Lake this way:

“Among the many beautiful lakes in this region, Lake McDonald stands without peer. It is a little gem. Hemmed in by colossal mountains whose tops tower into cloud-land, its sleepy waters present an air of ease and indolence that is most captivating.”

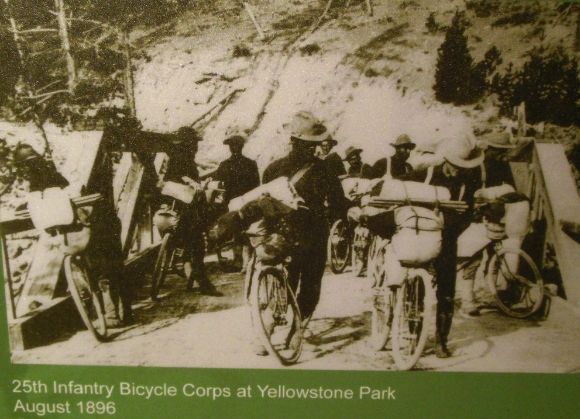

The Yellowstone Trip:

In 1896, the Corps made a trip from Fort Missoula to Yellowstone National Park and back: a total distance of 800 miles in all. Since the route paralleled rail lines, Lt. Moss had army rations sent ahead to the rail stations along the way. This reduced the load which the soldiers had to carry and gave them an incentive to cover the planned daily distances.

Crossing the continental divide proved to be an interesting challenge: not going up, but rather the problems of coming down the steep descent. Lt. Moss wrote:

“The grade was so steep that we could not ride down—had to roll our wheels the whole way down—had to use brakes until we had cramps in our fingers to prevent wheels from getting away from us—was without a doubt hardest work so far on the trip.”

There were also problems with the bicycle tires during the trip. When they were about 30 miles from Fort Yellowstone, two of the bicycles had tires that had disintegrated and could no longer be ridden. As a result Privates Haynes and Proctor were left behind with their disabled bicycles, food, and a dollar. They were instructed to walk the rest of the way to Yellowstone. In a rather interesting turn of events, the Bicycle Corps camped that night at Yankee Jim’s about 18 miles from Fort Yellowstone. Walking their bikes in the moonlight, Haynes and Proctor passed Yankee Jim’s. The next morning, the Bicycle Corps was surprised to find that Haynes and Procter were actually ahead of them.

In Yellowstone National Park, the members of the Bicycle Corps visited with the soldiers stationed there (this was prior to the creation of the National Park Service and the Army was responsible for the protection of the Park and law enforcement). They installed new tires and spent a week leisurely touring in the park. With regard to their first day of sightseeing in Yellowstone, Lt. Moss wrote:

“For miles we fared along the windings of the road, with the ever beautiful waters of the Gibbon River at our side, now admiring this, then admiring that. Indeed this was the very poetry of cycling.”

The St. Louis Trip:

Following the success of the 1896 Yellowstone trip, Lt. Moss began planning for a trip from Fort Missoula to St. Louis and back during the summer of 1897. This expedition would include 20 soldiers and would use new bicycles. The new bicycles, modified according to suggestions by Lt. Moss, were again made by Spaulding. Among the modifications were steel wheel rims with extra heavy side forks and crowns. Spaulding also provided leather frame cases and a luggage system that doubled as cooking pots.

Tires had been a problem during the Yellowstone trip and so Lt. Moss tested eight different varieties.

During the trip to St. Louis, the troops carried only a two-day supply of rations. As in the trip to Yellowstone, the route paralleled the rail ways. Thus Moss arranged with the Quartermaster’s Department to have rations sent ahead and placed at 100 mile intervals along the route. This meant that the troops had to travel 50 miles per day.

During their 41-day, nearly 2,000 mile trip to St. Louis, the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps encountered not only a variety of different terrains, but also adverse weather conditions. In the sand hills of Nebraska, the roads were impassible, so the men once again followed the railroad tracks instead of the road. Several of the men, including Lt. Moss, became sick. With regard to his soldiers, Moss reported:

“Some of our experiences, especially while in the sand hills of Nebraska, tested to the utmost not only their physical endurance, but also their moral courage and disposition; and I wish to commend them for their spirit, pluck and fine soldierly qualities that they displayed.”

In St. Louis, the black 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps was met by an enthusiastic crowd of about 1,000 cyclists who escorted them into the city. The

St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported:

“There was quite a crowd of pleasure-seekers and wheelmen at the Cottage in Forest Park to greet the soldiers. As the mounted police rode up the hill, followed by the local wheelmen and then the travel-stained soldiers, three hearty cheers of welcome were given by the crowd at the Cottage.”

According to the

St. Louis Post-Dispatch:

“They moved swiftly up the hill as perfect in formation as a troop cavalry. When the word ‘halt’ came they dismounted and their faces were illumined with broad grins. The end of their adventures had come.”

It is estimated that about 10,000 people visited the Bicycle Corps at their camp.

According to one newspaper account, Lt. Moss predicted:

“I don’t know how soon it will come, but I am confident that will not be long until every company in the United States army will have a Bicycle Corps of from ten to twenty men.”

After the journey to St. Louis, Moss reported that:

“The bicycle, as a machine for military purposes, was most thoroughly tested under all possible conditions, except that of being under actual fire.”

In St. Louis, Lt. Moss requested permission from the War Department to continue on to St. Paul, Minnesota, but his request was denied. Rather than bicycling back to Fort Missoula, they travelled by train.

The End:

Back at Fort Missoula, Lt. Moss requested that the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps travel from Fort Missoula to San Francisco. The proposal was endorsed by Colonel A. S. Burt:

“It is well known there is a prejudice against the colored man…It is a wise policy to educate the people to become familiar with the colored man as a soldier…The expedition proposed by Lieutenant Moss would be a fine educator.”

History intervened in the form of the Spanish-American War. The African-American Army units were called to service in Cuba and the bicycle experiment ended. The experiment proved the military viability of the bicycle and, just as important, the courage and strength of black soldiers.

James Moss, the young officer who started the experiment, would eventually rise to the rank of Colonel and would write several books on soldiering.