One of the first writing systems was developed about 3500 BCE in Sumeria. This writing system, called cuneiform, used a stylus to write on clay. As writing became more popular over the millennia, many people wrote with pen and ink on paper. A brief history of pens and ink follows.

Quill Pens:

Quill pens came into existence about the sixth century BCE. People soon found that long wing feathers from swans, turkeys, and geese worked best. The feathers were first plucked (or found) and then dried. Next, all of the oily and fatty materials which might interfere with the ink had to be removed. The quill was dried with the application of gentle heat.

Feathers from the bird’s left wing are best for right-handed writers because the feather will curve over the back of the hand away from the sight line.

To use the quill pen, the writer must sharpen it with a knife. As the point dulls, it is easily re-sharpened. The quill knife was designed especially for cutting and sharpening quills. This knife, unlike the later pen knife or desk knife, has a blade that is flat on one side and convex on the other. This makes it possible to make the round cuts required to shape the quill.

The pen is dipped in an ink well to fill the hollow shaft of the feather which works as an ink reservoir.

The painting by Philip van Dijk (1683-1753) shown above portrays a bookkeeper sharpening a quill pen.

Christian monks, such as those in the Irish monasteries, produced beautiful manuscripts using quill pens.

While feathers from swans, turkeys, and geese were most frequently used, some writers also used feathers from crows, eagles, owls, and hawks.

Steel-Point Pens:

A major advancement in writing came in 1780 when John Mitchell in Birmingham, England developed a machine-made steel pen point. This pen was sturdy, simple, and could be mass produced to provide a relatively inexpensive writing implement.

In 1830, James Perry, an Englishman, was granted a patent for a steel-point pen with a hole at the top of the central hairline slit. This was joined on both sides by additional slim slits. The design of this new pen point provided a slow and steady flow of ink and provided a smoothness superior to the earlier steel-point pens.

It should be pointed out that there were earlier metal-tipped pens. Archaeologists have found bronze pen points in the ruins of Pompeii, Italy.

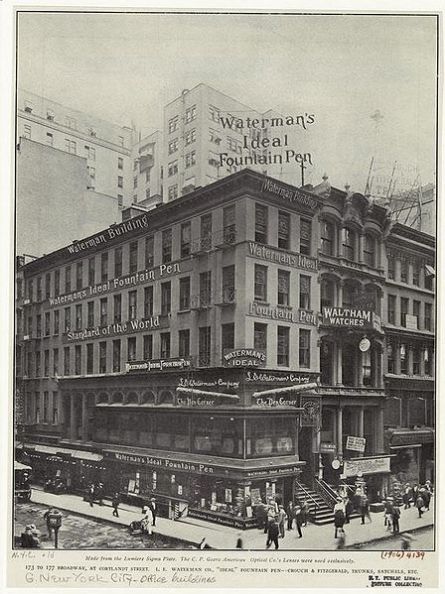

Fountain Pens:

The next major advancement in writing came with the invention of the fountain pen. Initially, the fountain pen had a major drawback: the ink reservoir was a thin cylinder which had to be filled with an eyedropper. In addition, the inks during the early nineteenth century had a tendency to clot before reaching the pen point.

In New York City, a stationer named L.E. Waterman patented a practical ink-filling system in 1884. Waterman used a pliant rubber chamber and a lever on the exterior of the pen. When the lever was lifted it squeezed air from the chamber, creating a vacuum. When the lever was released, ink could be sucked into the reservoir. Waterman’s name soon became synonymous with the fountain pen.

Waterman’s Ideal Fountain Pen factory is shown above.

During the twentieth century, the fountain pen underwent a number of innovations, including the use of a replaceable ink cartridge.

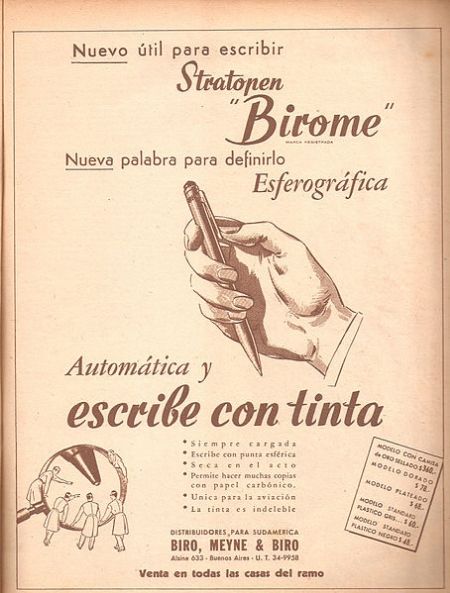

Ballpoint Pens:

The idea of using a rotating ball to distribute the ink to the paper was developed by the American inventor John H. Loud. His first patent for a ball dispenser pen was issued in 1888. This first design was intended for writing on rough surfaces, such as cardboard. Loud’s designs—he was issued several more patents—never reached the point of providing the user with the flow of ink needed for good penmanship.

It was up to Lazlo Biro, a Hungarian living in Argentina during World War II, to use a spin-off of war technology to create a pen which could write on paper. In 1943, Lazlo Biro and his brother Gyorgy form Biro Pens of Argentina. Their design was licensed for production in the United Kingdom to supply the Royal Air Force who had found that the ballpoint pens worked better than fountain pens at high altitude. In 1945, Marcel Bich bought the patent from Biro and the pen became the main product of his Bic Company.

Shown above is a 1945 advertisement. In many parts of the world, the ballpoint pen is known as a biro.

By the 1950s, the new technology became known for its reliability. The pens at this time used a precisely ground ball in a housing with four to six grooves which distributed the ink to the ball. These grooves helped distributed the ink evenly.

Ink:

All of the devices described above (except for the stylus and clay) require ink. For the origins of ink, we have to turn to ancient Egypt, particularly the Old Kingdom. The ancient Egyptians used reed pens and needed ink. By 2697 BCE the Egyptians appear to have developed ink. Their ink obtained its black color from carbon black or from finely pulverized pin ash. These elements were added to lamp oil which contained a gelatin made from boiled donkey skin. Unfortunately, this meant that the ink didn’t smell very good, so the Egyptians added musk oil to give it a better smell.

The ancient Egyptians weren’t the only ones playing with ink at this time: sometime in the 23rd century BCE the Chinese were exploring the use of natural dyes mixed with graphite and water to produce an ink that could be applied with brushes.

India ink was developed in India during the fourth century BCE. It was made from burnt bones, tar, pitch, and other substances. Writing was done using this ink and a sharp pointed needle.