The NSA Programs Are Constitutional Because The Constitution Sucks on Electronic Surveillance and Always Has

We have to face an unsettling fact: The Fourth Amendment sucks. In the light of recent revelations by Edward Snowden in the Guardian and other media outlets that the NSA and FBI are engaged in widespread, indiscriminate collection of electronic data about phone calls, email, and social media, some media and blogosphere commentators have angrily denounced these programs as unconstitutional or illegal.

These programs may be outrageous. They may violate your sense of privacy. They may be expensive boondogles and they may be ineffective. They may make certain of you very uneasy about ordering your, ahem, "medical" marijuana from your, ahem, "medical marijuana dispensary" because apparently those phone records are now stored by the NSA for an undisclosed or indefinite amount of time.

But one thing they are not is unconstitutional. That's because contrary to popular opinion, the Fourth Amendment protections against certain kinds of searches and seizures -- wiretaps and electronic intercepts, for example -- are extremely, extremely weak.

So let's take a look at what the Constitution and Supreme Court actually say about electronic eavesdropping. The reason the debate over the NSA sometimes seems unbridgeable is that some commentators are evaluating it by the standard of what the law actually is, while others are evaluating it by the standard of what they would hope the law to be, or believe it to be. To paraphrase Donald Rumsfeld, we go into this struggle over electronic privacy with the Fourth Amendment we have, not with the Fourth Amendment we might like to have.

The Supreme Court has never held, for example, that the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution forbids the government from intercepting and recording electronic communications during warrantless searches or seizures; it has only issued decisions about how evidence obtained by such searches can be used in trials. For most of U.S. history, the Supreme Court gave an implicit green light to nearly unlimited electronic surveillance, eavesdropping and wiretaps by the government, and for most of that period, the government used that authority with reckless abandon.

The reason this is important to anyone who would like to change the NSA program and other forms of electronic surveillance, is that the Obama administration has been responsive to progressive critiques on many occasions. The president has said he wants to have a debate about the balance between security provided by electronic surveillance on one hand, and privacy required by the traditions of the Bill of Rights. The administration is responsive to critiques based on reality and empiricism; but, however, it has been dismissive of counter factual critiques, hyperventilating or strategies it considers illogical. In other words, if you actually want to change these programs, and have the administration listen, you can't start with a false premise, and the idea that the administration is violating the Constitution (or that President Obama as a former constitutional law professor should "know better") is a false premise.

Moreover, too much of the commentary is erasing our collective history. Too much of the commentary about the NSA programs posits a rosy past when law enforcement or intelligence agencies "obeyed the Constitution," as compared to this administration's "unprecedented" expansion of surveillance. This false history not only lets the Bush administration off the hook for its truly unprecedented and illegal use of surveillance but elides the awful 20th century history of the use of electronic surveillance to repress racial and ideological minorities, to undermine democracy, and to wage campaigns of imperialism and murder overseas.

If there's one thing that I've found characterizes the Obama administration, it's that they scrupulously adhere to the Constitution and the law. President Obama really is the "law professor president." The problem is that the administration adheres scrupulously to the letter of the law even if it seems that they sometimes miss the spirit of the law. There will be no real scandals in this administration (as opposed to made up fevered dream scandals). No drama Obama is for real.

Once you understand through empirical legal analysis that the administration adheres scrupulously to the letter of the law, you realize that with issues like the NSA, the public is reacting to the fact that the law sucks. In the area of electronic eavesdropping, wiretapping and surveillance, it has sucked for a really, really long time, and it actually sucks a lot less under this administration than the Bush administration, even though it still sucks. The public is reacting to the fact that we are back in Clinton era legal sucktitude, and that the pre-Bush past was not as rosy as we thought it was.

For example, consider this revelation by Steve Kroft, a host of CBS's "60 Minutes," about the NSA, which The New Yorker reminded its readers about back in June when the story broke:

STEVE KROFT, co-host:

If you made a phone call today or sent an e-mail to a friend, there's a good chance what you said or wrote was captured and screened by the country's largest intelligence agency. The top-secret Global Surveillance Network is called Echelon, and it's run by the National Security Agency ...

I would tend to trust "60 Minutes" because their broadcasts are

meticulously fact checked, unlike certain bloggers, online pundits and "new media." You might think that this "60 Minutes" episode is piggy backing on the Guardian and Glenn Greenwald in exposing the NSA's program which basically, under the Obama administration, seems to record and screen the content every single phone call and email. If so, you would be wrong, because the date of

this broadcast was February 2000. In other words, during the last year of the Clinton administration, 60 Minutes reported that the content of a substantial proportion of every phone call and email was being recorded and screened by the NSA or by its partner signals intelligence agencies in the U.K., Canada or Australia (as explained below, the partners were encouraged to spy on each other as this was an important means for each government to get around national privacy policies). This would obviously get worse during the Bush administration. The other main change between the Clinton era and the Obama era is that the technology has gotten better and cheaper, and therefore the capacity for recording electronic communications has grown exponentially.

But, commentators who are angry, upset or surprised because they believe the Obama administration has created a new or unprecedented level of NSA eavesdropping on average Americans, were simply uninformed about the nature of U.S. signals intelligence and the NSA. If they were angry and upset that the Obama administration did not dismantle certain NSA programs that have been in place for decades, their critique would be on firmer ground.

Constitutional Protections for Electronic Communications Are Still Shaped by Law of the Age of the Horse and Buggy, Player Piano and Telegraph: Or Why Telegraph Law Affects the NSA

Despite the explosive growth in technology, in many ways the law of electronic surveillance is grounded -- one might say stuck -- in a conceptual framework of the pre-technological age, starting with the text of the Fourth Amendment itself:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

I don't mean to point out the obvious, but

the Fourth Amendment makes no mention of telephone calls, email, credit card transactions, tweets, cell phone locations or that embarrassing picture of your dog in floppy hat on Facebook. Obviously such things had not been invented. Even the telegraph hadn't been invented.

I'm not a strict constructionist at all, so I totally get the argument that an email is an awful lot like a letter was 200 years ago. But I am a legal positivist and a legal realist (and I want to admit my bias here--although positivism is an epistemological bias, not an ideological bias, as people across the political spectrum have adopted positivism). That means that when I want to know what the law is, I look to the law books and their recording of what the authoritative legal institutions have said the law is. That doesn't mean the law is good or that I agree with it or don't think it could be improved with better law. But I prefer to know what the law actually is, and the law is what the law does. The law is not what Glenn Greenwald says he thinks it should be.

My point is that because email, telephones and the like aren't mentioned in the Constitution, the Constitutional law of electronic interceptions is entirely Supreme Court made Constitutional law. The Fourth Amendment applies to telephones and emails only to the extent the Supreme Court has through interpretation expanded the amendment to cover these forms of communication and Congress has enacted laws to protect those court made rights. The decisions and opinions of the Supreme Court are the sole source of the minimum protections provided by the Fourth Amendment for electronic communications.

There's a cliche in legal studies: Where there's a right, there's a remedy.

Conversely, if the law does not provide a remedy, then there is no right. And a right is defined by the scope of the remedy the law gives a claimant. To use an example unrelated to the Fourth Amendment, we all know that the First Amendment provides for the separation of church and state. But what does that mean in practice? It depends on how the Supreme Court has interpreted that right. It means that a school child can sue to prevent his teacher from leading the class in prayer -- that is the school child's remedy. It does not mean that a school child can prevent his teacher from saying a silent, private prayer on school property in the teachers' lounge, nor from wearing a yarmulke or crucifix while teaching, nor from tithing part of her state issued paycheck to her local church. The scope of First Amendment remedies is set out in Supreme Court opinions and not in the text of the Constitution, which does not interpret itself or execute itself.

Generally, Constitutional remedies are described in Supreme Court decisions, opinions and orders, although Congress may and has shaped rights and remedies through plain legislation that includes enforcement mechanisms, and, as in the Fourth Amendment context, Congress can provide even broader rights and remedies than the Court. But when Congress enacts laws to provide more expansive protections of rights than the Constitution and the Supreme Court, it can also take away some of those expansive protections without violating the Constitution -- which is what has happened with the Patriot Act and several related amendments.

Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has not protected electronic communications particularly vigorously. The reason the Supreme Court's Fourth Amendment rights to electronic privacy are so weak is that the court has provided almost no useful remedies (outside of the context of criminal trials).

Historically, the rights the Supreme Court has provided under the Fourth Amendment to electronic privacy have been weak in part because of the wording of the Amendment and the context in which it was enacted. The Fourth Amendment talks about things and places -- persons, houses, papers and effects -- and for a long time it was difficult for courts to comprehend the idea of a right to privacy of information separate from the paper it was written on or the home and property where it was stored. Historically, the Constitution's drafters and many courts of the 1800s and early 1900s envisioned "search and seizure" as a problem of law enforcement officials breaking down doors, over turning desks, and grabbing every conceivable paper around regardless of relevance to a criminal investigation, and physically assaulting residents. "Search and seizure" usually involved acts that would have been criminal if carried out by civilians -- violent trespass, robbery, burglary, theft, conversion, assault and battery. It wasn't until 1967 (as explained below) that the Supreme Court finally seemed to embrace the idea of unreasonable search and seizure of information as being separate from trespass and theft.

The first laws against eavesdropping in England and colonial America were aimed at private citizens and shaped by the idea of trespass. Eavesdropping literally meant standing near the eaves of a home (a part of the roof) and listening to conversations taking place inside. This was considered a petty crime in England and colonial America. When law enforcement officials eavesdropped to get evidence, courts in England decided that the evidence was legal despite the fact that it had been obtained during the course of a petty criminal violation. The courts of the states and of the United States followed those precedents. Evidence that a law enforcement agent obtained illegally was, therefore, nevertheless generally admissible in court.

Electronic eavesdropping first became a problem with the first electronic means of communication -- the telegraph. Again, it was mostly a crime committed by private citizens. When telegraphs made communications across the entire U.S. instantaneous in the mid 1800s, they revolutionized life -- from business to politics to military affairs, to even the very conception of what time and distance were. Simultaneity across vast distances was an entirely new way to think about the world. Businesses in San Francisco could trade on information in New York. But because telegraph messages were expensive and there were bottlenecks in the network, businesses began trying to steal information from each other by tapping telegraph wires. Early statutes made tapping the telegraph lines a crime.

Before looking into how the law reflected the functioning of the telegraph, it's worth pointing out for younger readers just what the device was and because, remarkably, the vocabulary of the telegraph governs to some extent, the NSA's collection of metadata. (Telegraphs have disappeared other than as historical objects and science projects.)

The telegraph was a remarkably simple but powerful device. At it's most simple, it's just an electromagnet (at the receiving end) connected to a switch (at the sending end). A piece of metal is suspended over the electromagnet. When the sender taps the switch or key, the magnet draws the piece of metal on the receiver down with a loud click; when the sender releases the switch the metal piece on the receiver rises. Samuel Morse invented a useful signal code of short clicks and long clicks (dots and dashes) representing the letters of the alphabet. The signal clicks travel along the wires at the speed of electricity, which is almost the speed of light, or practically instantaneously whether the sender and receiver are a foot apart or 1000 miles apart. It's really remarkable when you consider that the telegraph replaced the next fastest method of communication -- the pony express -- a system of fast young horseriders galloping between stations strung out across the western part of the country; the pony express could deliver a message between the midwest and California in 10 days; the telegraph in nanoseconds. Telegraph operators became extremely "fluent" in sending code, listening to code and writing it down, pretty much at the speed of conversation, as legendary radio host and story teller Jean Shepherd recounted of his days in U.S. Army signal corp. Ironically, compared to analog telephones of the 20th century, telegraphs were digital in the sense that all data was reduced to a code similar to ones and zeros (dots and dashes). When wireless telegraphy was developed, and people could communicate freely across great distances, it became astonishingly like the current internet, as Shepherd also recounted.

The first time that a national defense emergency showed the limits of electronic privacy was during the Civil War. President Lincoln became completely beguiled by the telegraph, and became the first president to be able to direct strategy of his generals in real time. He often moved out of the White House for days at a time to work in a special telegraph office set up for him and the Union forces. One of the bloodiest early battles of the Civil War -- Antietam -- was in part over telegraph lines (as well as rail lines), and the threat of Confederate forces to cut Washington's communications with the rest of the Union. Eventually, Lincoln seized the assets of telegraph companies, had the federal forces build thousands of miles of dedicated military telegraph lines, censored private telegraph messages, limited private telegraph messaging by the general public, and created a system that subordinated the telegraph companies to the military needs of the Union, not completely unlike the way the Bush administration subordinated the telecom companies to the needs of the "war on terror."

Although telegraphs were generally operated by young men who were fluent in Morse code, eventually many telegraph receivers became equipped with a pen to replace the clicker and a slowly moving roll of paper. This code writing device was called a "pen register." When telephones replaced telegraphs for most daily use, any device at a telephone company's offices that automatically recorded information about an outgoing call from a phone was also called a pen register. This is the kind of information that in the current debate is called "metadata" -- that is, information about the call, but not the content of the call. Pen registers in phone companies routinely recorded metadata for billing purposes. Devices that recorded information about what numbers were called into a particular phone called were termed "trap and trace" devices. Law enforcement and intelligence agencies used pen registers and trap and trace devices throughout the 20th century. Despite the fact that a pen register was originally a simply telegraph recording device, when Congress enacted certain restrictions on recording metadata in the 1986 Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA), the sections governing such devices were called the "Pen Register Act," even though no pens are used. These rules (discussed below) were extended to "trace and trap" devices. Federal statutory rules provide for a much lower standard -- in terms of the level of suspicion generating the law enforcement or intelligence agency's need to install metadata recording devices. Yet these standards are higher than the standard provided by the Supreme Court, which has ruled that metadata has no Constitutional protection whatsoever, and that no warrant is required to acquire it. So if you're wondering why the NSA thinks it can scoop up trillions of bits of metadata without warrants (even though it has in the recent revelations asked for them), it's because, among other things, a section of the ECPA that is named after a bit of telegraph equipment.

The Telephone Age: Olmstead v. United States, the Rise of J. Edgar Hoover, and the Death of the Fourth Amendment for Electronic Communications

The first time the Supreme Court faced the issue of whether it was legal for law enforcement authorities to use telephone wiretaps was in 1928 in the case of Olmstead v. United States. Although the media today has generally framed the debate about the NSA and wiretapping almost exclusively in terms of terrorism, for most of the 20th century, the wiretapping issue was raised in a wide variety of circumstances, but most of the cases that came before the Supreme Court were about organized crime prosecutions -- especially bootlegging during prohibition and gambling. Generally, these cases involved federal prosecutors and the FBI (or its federal precursors), and not the NSA, whose main job, historically, has been espionage against sovereign states and militaries; the NSA grew out of war time military signals intelligence (that is, military and diplomatic code breaking). Olmstead v. U.S. was a more typical federal case and the defendant was a bootlegger running a massive liquor smuggling business, and he was convicted on the basis of wiretaps of his office.

The Chief Justice at the time, William Howard Taft, wrote the majority opinion. Taft is one of the most unusual justices in history because he was the only justice who was a former President of the United States. Taft is somewhat difficult to categorize in terms of the politics of the time. For a while, he was considered Theodore Roosevelt's political heir as leader of the progressive movement within the Republican party, but as president he disappointed Roosevelt for his cautious and pro big business approach and his overall political ineptitude. As Chief Justice -- a job Taft had wanted all his life, far more than being president -- he was also cautious and emphasized the "rule of law," which to him seemed to represent a preference for simply keeping the law as it was. The Court decided that a telephone conversation was not like papers and letters, and the prosecution could introduce evidence from the wiretap even though it had been carried out without first obtaining a warrant.

What I find most fascinating about Olmstead and other cases of the time is how difficult the court found it to grasp of the idea of information as being separate from things. The opinions also give us tremendous insight into how out of control law enforcement was at the time. So before you can fully appreciate the reasoning of Olmstead, you have to understand the prior Supreme Court case that Omstead was a direct reaction too -- Weeks v. United States, arguably the most important case on the Fourth Amendment the Supreme Court has ever decided because it was the source of the main remedy the court has applied in search and seizure cases ever since -- simply excluding evidence obtained without a warrant from criminal prosecution.

Weeks was also a federal prosecution -- in this case of a defendant who was running an illegal lottery, despite having a full time job at a business. Weeks was arrested by the police, while other police searched his residence without a warrant and confiscated various books and papers which they turned over to a federal marshal, who also then searched the residence without a warrant.

What's fascinating, though, is the description of the scope of the seizure -- they broke down Weeks's doors and took his stocks and bonds (worth over $12,000, which was a lot back then), heirlooms, "all of his books, letters, money, papers, notes ... insurance policies, deeds, abstracts, and other muniments of title, bonds, candies, clothes, and other property." It's also fascinating that Weeks seemed mainly concerned with getting his possessions back; he petitioned the prosecutors for their return. Eventually, they returned some of his possessions, but retained material they thought was relevant to the prosecution. The Supreme Court held in favor of Weeks, deciding that as a deterrent to unreasonable searches and seizures without a warrant, the seized evidence could not be used against Weeks at trial. This was the birth of the "exclusionary rule." The Court made passing reference to the dreadful state of citizens' rights under the law enforcement practices of the day:

The tendency of those who execute the criminal laws of the country to obtain conviction by means of unlawful seizures and enforced confessions, the latter often obtained after subjecting accused persons to unwarranted practices destructive of rights secured by the Federal Constitution, should find no sanction in the judgments of the courts, which are charged at all times with the support of the Constitution, and to which people of all conditions have a right to appeal for the maintenance of such fundamental rights.

One of the aspects of the debate about the current NSA scandal I find perplexing is the number of commentators, bloggers and even respected, knowledgeable journalists who posit that before the war on terror there was a golden age stretching back to the founding fathers when the Fourth Amendment was sacred -- something I heard for example Robert Scheer say a few weeks ago on NPR. This is simply nonsense.

The age of Weeks and Olmstead was the age of lynching (assisted by local law enforcement); police beatings and forced confessions; summary rounding up of political "undesireables," like communists, socialists, union organizers, civil rights advocates and pacifists; and the routine seizure of evidence without a warrant, and as I'll show below, unconstrained wiretapping and electronic surveillance.

This was, moreover, an era when the Fourth Amendment didn't even apply to states, and hence not to local law enforcement. The Bill of Rights would only be applied to the states on a case by case basis during the 20th century under the doctrine that the Fourteenth Amendment "incorporated" the Bill of Rights making them applicable to the states. The Fourth Amendment only became applicable to state and local governments in 1949.

So the question before the Court in Olmstead was whether the rule in Weeks -- that evidence seized in violation of the Fourth Amendment could not be introduced at trial -- was applicable to phone call wiretaps.

Justice Taft focused on the fact that the Fourth Amendment was about tangible things:

The well known historical purpose of the Fourth Amendment, directed against general warrants and writs of assistance, was to prevent the use of governmental force to search a man's house, his person, his papers and his effects, and to prevent their seizure against his will.

Taft also distinguished phone calls from letters, which even while possessed by the U.S. Post Office, could not be opened and searched, and in several passages emphasized that the wiretap took place outside Olmstead's office, in the basement of the office building, and that there hadn't been any trespass of an actual place:

The United States takes no such care of telegraph or telephone messages as of mailed sealed letters. The Amendment does not forbid what was done here. There was no searching. There was no seizure. The evidence was secured by the use of the sense of hearing, and that only. There was no entry of the houses or offices of the defendants.

By the invention of the telephone fifty years ago and its application for the purpose of extending communications, one can talk with another at a far distant place. The language of the Amendment cannot be extended and expanded to include telephone wires reaching to the whole world from the defendant's house or office. The intervening wires are not part of his house or office any more than are the highways along which they are stretched.

Taft made one prescient prediction, though -- that Congress could if it wanted provide more protection to telephone privacy than the Court was willing to provide.

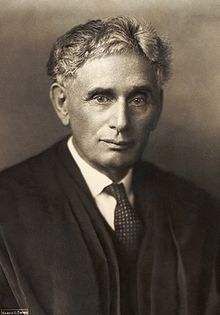

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes agreed with Justice Taft, but showed his disdain. He called wiretapping a "dirty business" and noted that wiretapping was a crime under the state law that was applicable although not under federal law, and that the government should not be obtaining evidence through criminal behavior.

Justice Louis Brandeis dissented with a more prescient analysis. He noted that technology was changing quickly and could invade anyone's most intimate privacy, and that the crude violent searches and seizures of the past were not the only unreasonable searches the Constitution should protect against under these evolving technological circumstances:

"We must never forget," said Mr. Chief Justice Marshall in McCulloch v. Maryland ... "that it is a constitution we are expounding." Since then, this Court has repeatedly sustained the exercise of power by Congress, under various clauses of that instrument, over objects of which the Fathers could not have dreamed...

When the Fourth and Fifth Amendments were adopted, "the form that evil had theretofore taken" had been necessarily simple. Force and violence were then the only means known to man by which a Government could directly effect self-incrimination. It could compel the individual to testify -- a compulsion effected, if need be, by torture. It could secure possession of his papers and other articles incident to his private life -- a seizure effected, if need be, by breaking and entry. Protection against such invasion of "the sanctities of a man's home and the privacies of life" was provided in the Fourth and Fifth Amendments by specific language... But "time works changes, brings into existence new conditions and purposes." Subtler and more far-reaching means of invading privacy have become available to the Government. Discovery and invention have made it possible for the Government, by means far more effective than stretching upon the rack, to obtain disclosure in court of what is whispered in the closet...

The progress of science in furnishing the Government with means of espionage is not likely to stop with wiretapping. Ways may someday be developed by which the Government, without removing papers from secret drawers, can reproduce them in court, and by which it will be enabled to expose to a jury the most intimate occurrences of the home.

Brandeis realized, unlike Taft, that the Fourth Amendment was not just a protection against the government taking "your stuff"; but that read with the Fifth Amendment, it prevented the government from coercing a defendant into self-incrimination and confession through the use of your private communications against you. Brandeis also was ahead of his time in recognizing that

it was the information that was being searched and seized, and not just the piece of paper, and although he seems to have been envisioning X-rays as a technological way of seizing information, one of the reasons this conceptual leap is important in the digital age, is that information is now non-possessory and infinitely reproduceable. In the age of Olmstead, if the government seized my diary and took possession of it, I no longer had possession of my diary. We couldn't possess it at the same time. In the digital age (even back in the Xerox age), the government could seize the information on my on-line diary or email or digital wireless phone call without depriving me of possession of that information or the vehicle I put it in; they can possess my information without taking it from me, and without my even knowing they have done so. This is what Brandeis was foreshadowing.

Olmstead was the law for the next 40 years -- until 1967, and law enforcement at all levels had a free hand to spy on its citizens. Another justice noted for his sympathy for civil liberties, Justice Felix Frankfurter, tried to reign in the electronic snooping somewhat in a case, Nardone v. United States, that seems not to have been followed much. In 1934, the New Deal congress passed the Federal Communications Act, which sought to place regulation of electronic communications under the newly created Federal Communications Commission (FCC). It contained an ambiguous provision that made it a crime for an "employee" to disclose the contents of electronic communications. I think most observers thought that the clause applied to employees of the telephone companies and was intended to prevent them from listening in to customer conversations and disclosing to others what they heard. In a bit of a stretch, Frankfurter, wrote an opinion that said that this provision applied to all employees of all kinds, including federal agents while employed by the government, and that these agents could not disclose the content of wire taps in federal prosecutions without violating the statute, and that evidence procured through warrantless wiretaps wasn't admissible in court. But the problem with Nardone is that Frankfurter wasn't announcing a Constitutional rule; he was just interpreting a federal statute, and federal statutes could be changed by Congress. This case did set the precedent that Congress tended to provide more protections against wiretapping than the Supreme Court -- in essence creating statutory rights above and beyond the meager to non-existent Fourth Amendment right against electronic surveillance.

Even those meager federal statutory rights were no match for the man who would run rampant with federal electronic surveillance for nearly a half century, because around the time that cases like Olmstead and Nardone were being decided, J. Edgar Hoover was building the new federal law enforcement agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, into a cancer on American democracy and a Gestapo. I realize that calling Hoover's FBI a Gestapo risks proving Godwin's rule, but both Eleanor Roosevelt and President Harry Truman made the comparison. Truman wrote:

We want no Gestapo or secret police. FBI is tending in that direction. They are dabbling in sex-life scandals and plain blackmail… Edgar Hoover would give his right eye to take over, and all congressmen and senators are afraid of him.

Despite President Truman's misgivings, this era and the subsequent decades were the heyday of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, who then proceeded to wiretap virtually the entire political class -- and use the information obtained for influence and even blackmail. Curt Gentry's meticulously researched biography,

J. Edgar Hoover, the Man and His Secrets, argues that Hoover was literally unhinged.

The L.A. Times review of the book was entitled, "The Lunatic in Our Asylum" and notes:

But Hoover had a much more dangerous flaw, which many inside and outside the FBI noticed: He was, in a way, mentally deranged. One attorney general (the AG was, officially though not in fact, Hoover's boss) thought he was just plain nuts. The Kennedys often spoke of Hoover's "cartoonlike lunacy."

They were not referring merely to his idiosyncracies--his compulsive hand-washing, his becoming unhinged at the sight of an unswatted fly, his insistence that agents not step on his shadow, his fanatical anti-fat crusade (one agent, writes Gentry, "was given a letter of commendation for single-handedly breaking up a Soviet spy ring, then fired because of his weight").

They meant the kind of intense battiness, and threat, that Gentry best captures in this quote from an old FBI agent to a rookie, back in 1958: "You must understand that you're working for a crazy maniac and that our duty . . . is to find out what he wants and to create the world that he believes in ."

The lax Supreme Court jurisprudence about the Fourth Amendment's role in electronic surveillance combined with Hoover's successful blandishments of presidents gave Hoover a green light to carry out several types of illegal surveillance; historical accounts suggest that three of the most important techniques Hoover's FBI used were (1)

warrantless wiretaps, (2)

bugging and (3)

black bag jobs. A wiretap was a way of listening to a target's telephone conversations, and the tap could be placed at any number of places, from near the phone itself, to basements and utility rooms of office buildings, to wires outside on the telephone pole, to the telephone company offices. Bugging involved placing listening devices, like microphones and transmitters inside a target's residence. A black bag job was slang for breaking and entering a target's home or office -- that is, while carrying the tools of the trade of burglars in a black bag -- in order to snoop around, gather papers or place bugging or wiretap equipment.

Ironically, Truman, like every president before or after him during Hoover's tenure, used and abused the information that Hoover illegally acquired. For example, shortly after Truman became president, Hoover began providing Truman with wiretaps of U.S. citizens, including people prominent in the political scene in Washington, people completely not suspected of committing any crimes. Hoover had carried out wide ranging domestic surveillance during the war for President Roosevelt, mostly to search for Nazi sympathizers or communists who, although generally part of the progressive movement of the day, were also suspected of being more loyal to the Soviet Union than to the United States. Hoover used that authority to engage in wide ranging political surveillance, although President Roosevelt occasionally tried to reign Hoover in from irrelevant investigations.

Shortly after Truman was inaugurated, Hoover offered one of President Truman's top aids a memo that began, “I thought you and the President might be interested to know…” and that contained political gossip. This was how Hoover ingratiated himself with presidents, who then became Hoover's patron and protector, while also being dependent on Hoover and potentially Hoover's victim. Within a few weeks, Truman had through intermediaries asked Hoover to carry out illegal surveillance on a political rival, the legendary New Deal lawyer, Tommy "the Cork" Corcoran, who had gone into private practice in Washington as a fixer and lobbyist. Corcoran had a low opinion of Truman, and the transcripts of the surveillance Hoover provided Truman included observations that Truman was "dumb" and surrounded by "mediocre" political hacks from Missouri. Obviously this was catnip for the cat, and effectively gave Hoover a green light to continue wide ranging political surveillance of virtually the entire political elite. Hoover carried out surveillance of Corcoran for three years, even though he was not suspected of any crime or subversion.

Hoover even investigated Eleanor Roosevelt when she was First Lady and President Roosevelt was still alive, although the president managed to find out about and quash one such rogue investigation. After Roosevelt's death, Hoover stepped up his surveillance of Eleanor Roosevelt, in part because he didn't approve of her involvement in the founding of the United Nations, and Mrs. Roosevelt remained a target of Hoover for decades after, generating thousands of pages of investigative reports about her left wing, progressive and civil rights associations.

Like most Attorneys General, President Eisenhower’s, Herbert Brownwell, either declined or was unable to control Hoover’s wiretapping, even though officially, the FBI director was supposed to get approval for wiretaps from his boss, the AG, and Brownwell instead gave Hoover carte blanche to do as he pleased with the technique. Brownwell wrote that Hoover’s wiretaps and bugging were the only way to keep tabs on spies and subversives, and that they couldn’t be limited to criminal investigations for the purpose of prosecution because the “FBI has an intelligence function in connection with internal security matters equally as important,” and “considerations of internal security and the national safety are paramount and, therefore, may compel the unrestricted use of this technique in the national interest.”

Hoover "generously" and out of a sense of concern, provided Joseph P. Kennedy, the father of John F. Kennedy, with a transcript of one of the young Senator Kennedy's sexual adventures with a woman other than Jackie Kennedy, and even during the Kennedy administration made JFK and his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and nominally Hoover's boss, aware that he had information about about his affairs while president.

In the current debate, many commentators, who are ordinary people and bloggers, seem concerned that "their" information is being gathered, which is a legitimate concern. But what's missing from the discussion is the historical context, in which Hoover intimidated the entire governing class, affecting policy, laws and appointments. Hoover could prevent a judge from being nominated to the Supreme Court or a politician from getting a cabinet appointment simply by suggesting that he had damaging information on the person and that the person wouldn't pass the FBI's "background check." No attorney general could effectively supervise him and no president could ask for his resignation or fire him. President Nixon tried to fire Hoover twice; mysteriously after being called to the White House, Hoover left, still in his job, having somehow defeated Nixon.

Several boomer age DK members have mentioned obtaining information about their "FBI files" presumably generated during the 1960s. FBI files typically began with a report or investigation of one organization or person, sometimes not suspected of crime but simply deemed subversive, but under their operating rules, the mention of virtually anyone else in the report in turn generated a new file. In other words, being a friend or associate of a target of a secret investigation made that friend or associate, at least passively, yet another target. Estimates of the number of files generated this way range up to 55 million.

But in Hoover's FBI, the tip of the iceberg was more dangerous than the submerged iceberg. Hoover kept an entirely separate filing system for his personal use. Part of his office at FBI headquarters was considered Hoover's personal office, which his closest colleagues described as a place where he kept things like his stock certificates and tax returns. In this personal office, however, Hoover kept two sets of files on targets of FBI spying that Hoover considered not to FBI property. Officially, they were known as Hoover's "Personal" files and "Official/Confidential" files, but colloquially, they were known as Hoover's "secret files." While the official FBI files were scrupulously, meticulously indexed -- a legacy of the fact that one of Hoover's first jobs was working in the Library of Congress -- the secret files were indexed in a cryptic way that only Hoover and a few of his closest associates could understand. These were the most damaging, dangerous, and sensitive files that Hoover amassed.

When Hoover died somewhat suddenly in 1972, there was a mad scramble, which would have been funny if it hadn't been so tragic and scary, for the secret files . Nixon was determined to get some control over the rogue FBI -- not because he was a lover of the rule of law, but because Hoover had refused to carry out Nixon's own rogue spying operations. Nixon appointed L. Patrick Gray, an FBI outsider as Acting FBI Director, and one of his first most urgent assignments was to get control of Hoover's "secret files." Hoover's closest subordinates flat out lied to the new FBI director, claiming the files didn't exist. Meanwhile, Hoover's long time executive assistant, Helen Gandy, began destroying some of the files and moving others to the home of Hoover's long time domestic partner, Clyde Tolson. A virtual clown car of politicians and officials began the search for the secret files, including President Nixon, Attorney General Richard Kleindienst, Acting Director Gray, and CIA counter intelligence chief James Jesus Angelton. While Freedom of Information Act requests for official FBI files have shed a great deal of light on what kind of information the FBI was collecting on citizens, ordinary and elite alike, we'll probably never know what dirt was in the secret files, which Miss Gandy and other Hoover associates spent the next several months destroying.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Supreme Court began issuing opinions that supported civil rights, civil liberties and voting rights. But J. Edgar Hoover was unaffected by the changing political and legal winds. As discussed in detail below, in 1967, the Supreme Court finally decided that the Fourth Amendment applied to telephone wiretaps in the case of Katz v. United States. The only remedy provided in Katz, however, was the extension of the exclusionary rule to evidence obtained by illegal wiretapping, and this seems only to have spurred J. Edgar Hoover on -- as though the prohibition on the use of warrantless wiretap evidence in criminal prosecution was an approval of the use of warrantless wiretaps for everything other than criminal prosecution, from monitoring "subersives" to keeping tabs on members of the elite political and journalistic classes.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the FBI created a secret Counter Intelligence Program called COINTELPRO. While a full discussion of COINTELPRO would require an entire separate series of blog posts, some of the things that distinguished it from the electronic surveillance that Hoover had carried out before were that it was carried out on a massive scale; it targeted groups that even by Hoover's prior reactionary standards would not have been considered subversive, like peace groups, civil rights groups, women's rights organizations, and student organizations; it involved not just surveillance, but infiltration and disruption by FBI personnel as agents provocateurs, mass electronic surveillance, false planted news stories and smears, threatening anonymous phone calls, cooperation with local law enforcement to make false arrests and perjured police testimony to put activists in prison, and eventually assassinations.

As part of the program, Hoover's FBI targeted "Black Nationalist Hate Groups," which included Martin Luther King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Malcolm X's Nation of Islam. The program's targeting of the Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam probably contributed to the vehemence of the Nation's hatred for Malcolm after he divulged aspects of the sexual scandals surrounding the Nation's leader Elijah Muhammad, and Malcolm's eventual assassination. The iconic picture of Malcolm X standing by the window of his Queens, New York home has become a contemporary symbol of Malcolm's militancy and belief in self-defense "by any means necessary," but at the time, it was seen more as a symbol of the terrified paranoia that had engulfed Malcolm as a result of the endless stream of threatening phone calls, harassment and surveillance he received from both the Nation and FBI, and a year later, the firebombing of his home. With respect to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, in addition to applying the usual techniques, Hoover became obsessed with Dr. King's sex life and used black bag jobs and bugging to make extensive recordings of King's sexual affairs. On at least one occasion, he had transcripts anonymously forwarded to King's wife. Hoover also shared transcripts of King's sex life with Jackie Kennedy in order to turn the Kennedy family against King and the civil rights movement.

Ironically, just as President Nixon was escalating his pervasive electronic surveillance and harassment of his "enemies, " Hoover began cutting back on the FBI's illegal activities. Ironically, Hoover's new caution may have contributed to Nixon's Watergate scandal, because without the FBI to do his dirty work, Nixon decided to create an internal White House unit to carry out its black bag jobs, bugging and wiretaps directly. Only after Hoover's death and Nixon's resignation did the federal government begin to apply some semblance of Constitutional rule of law to electronic surveillance.

To put this in overall historical perspective, from the commercialization of the telegraph in the 1850s until today, Americans have only had a federal government at least publicly and nominally committed to not using wiretaps of their electronic communications and telephone conversations without a warrant, from the late 1970s (death of J. Edgar Hoover in 1972, the resignation of President Nixon in 1974, and passage of FISA in 1978) until September 11, 2001, and from the inauguration of President Obama and the suppression by CIA Director Leon Panetta and Attorney General Eric Holder of President Bush's warrantless wiretapping program in 2009 and today (4 years) -- or 27 years out of 170 years of electronic communication, about the lifespan of a recent college graduate out of a century and a half.

The regime that has replaced the Fourth Amendment lawlessness of the last 200 years, however, is deeply flawed. The Supreme Court has continued to refuse to provide meaningful remedies for warrantless wiretapping and other forms of electronic surveillance.

Congress has fitfully provided more protection than the Supreme Court has been willing to give, but what the Congress giveth, the Congress can taketh away.

Next installment:

Katz v. United States (1967) - Supreme Court finally decides the Fourth Amendment applied to telephone calls, but the only remedy is the exclusionary rule

United States v. United States District Court (1972) - In a criminal prosecution of radical activists, the federal government was found to have engaged in extensive warrantless surveillance of the defendants; although the Court wrote extensively about the purpose of the Fourth Amendment, the only remedy was sharing of illegally obtained evidence.

Smith v. Maryland (1979) - Electronic surveillance of a defendant using a "pen register" was not a search at all; the government need not get a warrant for telephone metadata, and metadata is completely outside the Constitutional protections of the Fourth Amendment.

Clapper v. Amnesty International USA (2013) - Organizations believing they may be subject to electronic surveillance under FISA amendments lack standing to bring Constitutional challenge.

How Snowden's revelations could help in the Amnesty International cases.

UPDATE: Hey all, I'm so honored to be in the Community Spotlight!