Humans have been called "the naked ape". But how did we get that way? When did early humans lose their fur, and why?

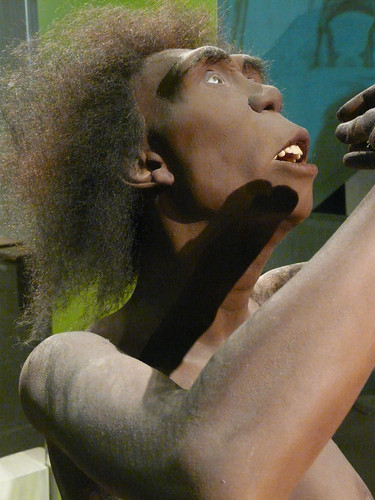

Homo erectus reconstruction (photo from Wiki Commons)

Evolutionary biology tells us, from fossil and DNA evidence, that the ancestors of humans and chimps began diverging from each other about 7 million years ago, in Africa. The earliest two-legged ancestors in the human line date back to around that time. Since all of our primate relatives are covered in fur, we can assume that our earliest ancestors had body hair too, and that we lost our fur sometime during our evolution, resulting in our current hairless condition. (Actually, humans are not "hairless"--we still have just as many individual body hairs as a chimpanzee does, but our hairs are short and very fine, making them nearly invisible.)

Unfortunately, fossils are not of much use in determining when this happened, since preserved skeletons don't have any hair. But anthropologists have used two clever indirect methods to determine when our ancestors lost their fur.

The first method centers around skin pigmentation. The intense tropical African sun can be dangerous to exposed skin, leading to melanoma cancers. Perhaps more importantly, high levels of UV radiation from sunlight can interfere with the production of a form of vitamin B called "folate", which is important in cell division and particularly in the development of fertilized eggs into embryos. Most animals, like our primate ancestors, protect themselves from the sun's UV waves with fur. The exposed skin on chimpanzees begins as light-colored when the chimp is young, and darkens with age, but the body skin under its fur remains light-colored. Humans in Africa, however, who lack fur, protect themselves from the harmful UV rays of the sun with a layer of the pigment melanin, which makes their skin dark. Therefore, Dr Alan Rogers, of the University of Utah, reasoned in 2001, we should be able to tell when humans lost their body hair by determining when this change in skin pigmentation occurred. Rogers began a study of the human gene known as MC1R, which controls the production of melanin, and found that while chimpanzees have several different variations in this gene, modern African humans have only one version, suggesting that the appearance of this gene marked the transition from hairy bodies (in which the level of melanin was relatively unimportant) and the loss of body fur and exposure of skin to direct sunlight (when melanin production became very important). By counting up the number of mutations in this gene and applying a "molecular clock" to determine how long it would take for these mutations to appear, Rogers was able to estimate that this switch came around 1.2 million years ago. It is likely that this change happened in our hominid ancestors Homo erectus (or Homo ergaster, depending on whether you are a lumper or a splitter). Before that time, we were furry animals with light-colored skin; after that, we were naked animals with dark-colored skin.

Another scientist, Dr Mark Stoneking of the Max Planck Institute in Germany, was at around the same time pursuing a different line of thought into the same question. Stoneking noted that humans have three different kinds of lice, which not only differ from those of our primate relatives, but also differ from each other. The head louse and the pubic louse make their living by using crablike claws to cling to our hair and sucking our blood with their needlelike mouthparts. But the human body louse, Pediculus humanus humanus, doesn't cling to our hair--instead it lives in our clothing. Since this louse must have evolved from the human head louse to specialize by living in our clothes, Stoneking reasoned, if we can determine when the body louse first appeared, that will tell us when humans first started regularly wearing clothing. DNA analysis showed that the human body louse evolved from the head louse sometime between 42,000 and 72,000 years ago. We've been wearing clothes since then.

Since we lost our body fur around 1.2 million years ago, and started habitually wearing clothes only 50,000 years ago, that means human ancestors were running around naked for over a million years. The reason for that may have something to do with why humans may have lost their body fur in the first place--sweating.

Chimps, like all furry mammals, cannot sweat. They have little need to--they live in dense shaded forests where little direct sunlight penetrates down to the ground. Animals that live out on the open savannah, however, do not have that advantage. They get the full force of the tropical sun, and since all mammals are warm-blooded and produce a lot of body heat, all of these savannah-dwellers face the problem of overheating (which can be deadly). Unable to sweat, most mammals "pant" (like dogs) when they begin to get overheated--the rapid in-and-out breathing helps cool the body by evaporating moisture from the lining of the mouth. African mammals also use behavioral methods to keep cool: many mammals are only active at night when the sun is down, and others such as elephants, hippos and rhinos, soak in water or mud during the day to cool themselves.

The earliest human ancestors, the Australopithecines, lived much like chimps: although they could walk bipedally across the grasslands, they were still good tree-climbers, and likely spent most of the day at the forest edge, foraging in the trees. By the time Homo erectus appeared, however, there was a drastic change in human body structure. The body had become thinner and taller, the legs had become longer, and the arms had become shorter. Homo erectus was capable of doing something that the earlier bipeds could not do--it could run. This adaptation may have opened up an entirely new ecological niche for our ancestors. Before this, hominids could only walk around, looking for fruit trees and perhaps scavenging for meat from abandoned predator kills. But with the appearance of Homo erectus, hominids were now capable of actively pursuing prey, most likely by hunting in groups and running prey down to exhaustion in relays, like wolves do.

But this produced an evolutionary problem. Running produces an enormous amount of heat, far more than can be dumped by panting. Hominids needed an entirely new system of keeping cool and preventing fatal overheating, and this took the form of sweat glands. By covering the skin in perspiration, cooling could take place quickly by evaporation. But sweat glands are only useful if the skin is directly exposed to the air. And hence, our Homo erectus ancestors lost their fur. They became naked apes.

Once hairlessness appeared in humans, it is likely that another evolutionary factor kicked in, known as "sexual selection". This is the process in which traits in one gender become preferentially selected by the other (like a peacock's tail), and thus spread throughout the population. Humans may have begun to select mates that had less body hair than the others in the group, perhaps because less body hair meant fewer parasites, or perhaps because hairless bodies were able to display better sexual signals.

Over time, the Homo erectus species (or its Homo ergaster relative) evolved into our modern species, Homo sapiens. This happened in Africa about 200,000 years ago. As our species expanded out of Africa and migrated around the world, it encountered environments in which the intense tropical rays of the sun became less of a danger--in fact in higher latitudes, UV light becomes an important factor in manufacturing vitamin D in the body. As a result, humans in tropical Africa and Australia retained their dark melanin pigmentation, while those in Asia and Europe reduced their melanin and developed lighter skins.