Almost since the foundation of the United States, the westward expansion of the country was guided by Manifest Destiny, the idea that it was the country’s destiny to span the continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific. By the middle of the nineteenth century, it was clearly evident that the way of westward expansion would have to involve railroads which could then transport raw materials (minerals, timber, cattle, grain) from the west to the east and manufactured goods from the east to the west. One of the railroads which was important in the implementation of Manifest Destiny was the Northern Pacific Railroad.

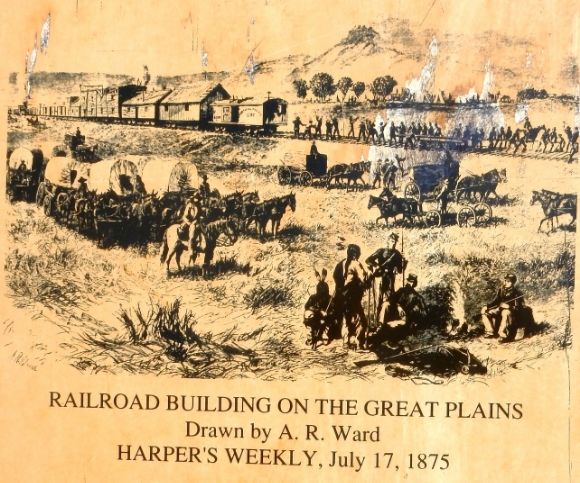

It was not unfettered capitalism that drove the railroads across the Great Plains to the Pacific Ocean, but capitalism nurtured and supported by the federal government. In 1853, the United States War Department dispatched five separate survey parties to map out the most economical and practical railroad routes. In 1854, Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens set out to impose treaties on the Indian nations of what is now Washington, Idaho, and Montana which would move Indians out of the way of the railroads and the non-Indian settlers that the railroads would bring in.

In 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed legislation which granted

“funds to aid the construction of a railroad and telegraph line from Lake Superior to Puget Sound.”

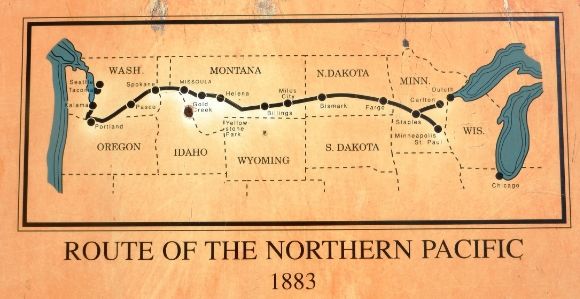

Jay Cooks and Company, a Philadelphia banking house, became the financial agents for the railroad in 1869. They broke ground for the new railroad near present-day Carlton, Minnesota in 1870 and soon brgan grading and track-laying. In 1871, they started construction in the west at Kalama, Washington. By 1873, the track from the east had reached Bismark, North Dakota. However, Jay Cooke and Company went bankrupt with a 1,500 mile gap between the two ends of the track.

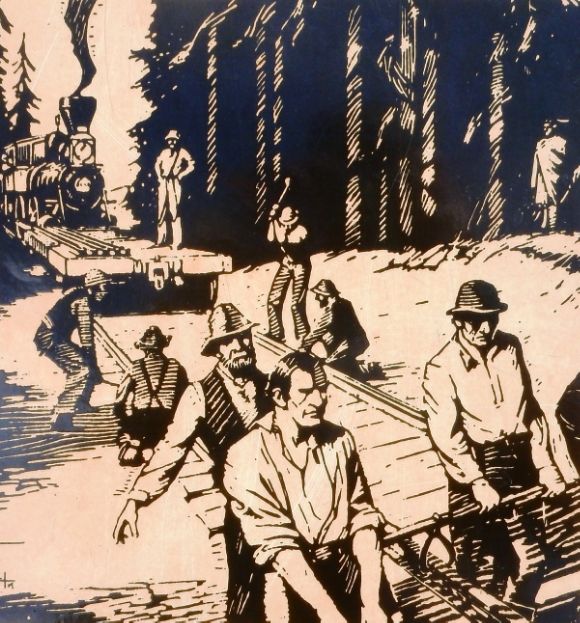

In 1875, the Northern Pacific Railroad was organized under the leadership of Frederick Billings and by 1878 construction had begun again. It has been estimated that construction of the railroad involved the efforts of 25,000 Chinese laborers, as well as countless other immigrants.

In 1881, the Northern Pacific reached the Yellowstone River at Miles City, Montana. This allowed for the direct shipment of buffalo hides to the east and increased commercial buffalo hunting. In 1884, the Northern Pacific sent its last carload of buffalo hides to the east. The once great herds were now nearly extinct.

American Indians were less than enthusiastic about the railroad cutting across their reservations and aiding in the decimation of the buffalo herds. In Western Montana, the Indians on the Flathead Reservation (Pend d’Oreille, Salish, and Kootenai) bluntly told the Americans that they did not want the railroad running through their land. In response the United States granted the Northern Pacific Railway a right-of-way through the Flathead Reservation. This right-of-way is 200 feet wide, plus land for depots, shops, and houses. A total of 1,430 acres are included. This was, in essence, a transfer of wealth from the poor (Indians) to the wealthy (non-Indians). The Indians were, however, promised compensation for the right-of-way as well as the opportunity for selling piles, ties, and cord wood during the construction. It would take a court case in the twentieth century to obtain adequate compensation.

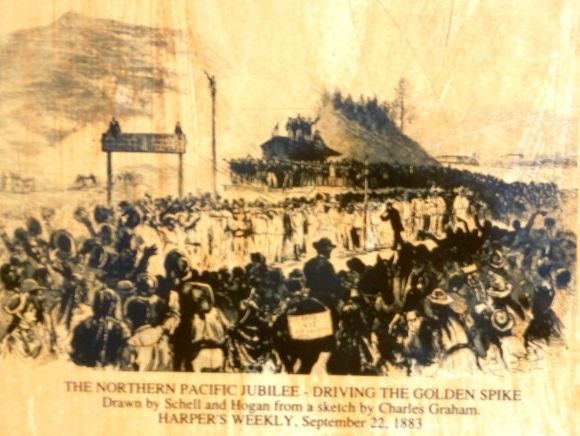

In 1883, the last spike of the Northern Pacific Railroad was driven at Independence (now Gold) Creek in Montana marking the completion of the first of the northern transcontinental railroads. The driving of the final spike was done with a ceremony which cost an estimated $250,000. The Fifth Infantry Band provided the music for the event. One reporter from White Sulphur Springs, Montana, wrote:

“During the driving of the last spike, the band played, one hundred guns were fired, and a general squabble prevailed. I have not as yet been able to find a Montanan who saw the golden spike, but I presume it was there and was driven. I stood only six feet away, but the crowd was so thick and so strong that I could not see the work performed.”

The map above shows the route of the Northern Pacific in 1883.

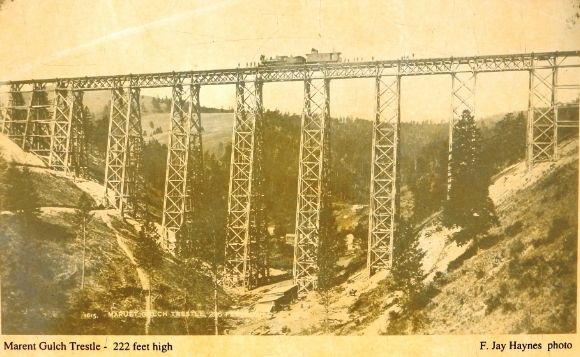

Construction of the railroad involved a number of engineering and construction challenges. For example, the Big Horn Tunnel, west of Glendive, Montana, was 1,100 feet long. Construction of the Mullen Tunnel, southwest of Helena, Montana, involved the use of electric lights for the first time. The Marent Trestle, west of Missoula, Montana, stood 222 feet high and was 750 feet long. It was built of timber and proclaimed the largest wooden bridge in the world.

Completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad also had consequences for the coastal tribes. The completed rail line, coupled with improvement of canning techniques, resulted in an increased demand for Northwest Coast salmon. This marked the beginning of the depletion of the once-great salmon runs and the exclusion of the tribes from the fisheries which had been guaranteed to them by treaty.