Iceland prides itself on its clean air and water. Icelanders are famous for asking tourists what they think of the water, and complaining about the water when overseas (primarily because our water here doesn't require chlorination so most people have never adjusted to the taste of chlorine). Likewise, most common types of air pollutants are rare here. The most common complaints you hear about concern hydrogen sulfide, which Iceland has a very strict limit on and which isn't even regulated in a large chunk of US states or by the US government ambient air standards.

Unfortunately, no matter how much we restrict industry, sometimes nature throws you a curve ball. Because in the entire Icelandic history of monitoring air pollution, never before have conditions been as bad as what is being experienced in the Eastfjörds now.

Join us below the fold for another Eldfjallavakt

A blue mist has descended across eastern Iceland. It was noticed shortly after the eruption began, first by making the sun look like sunset while still high in the sky. This is characteristic of sulfur dioxide pollution, which forms little droplets of acid that preferentially scatter blue light (thus making scattered blue light come from all sides, but scattering away most of the blue light straight from the sun).

Obviously, this calls for measurements. These measurements were done today. And the results were not good.

Umhverfisstofnun - Iceland's equivalent of the EPA - reports today that recorded SO2 measurements were as high as 660 µg/m³, well higher than anything ever recorded before in Iceland. So long as the eruption goes on at its current intensity, it's expected to be in the range of 500-1000 µg/m³ for areas downwind of the plume.

How much are these figures? As covered yesterday, the WHO standards for SO2 place a limit of 20 µg/m³ for 24 hours and 500 µg/m³ for ten minutes. Even brief exposure to the current SO2 levels in Austfirðir are above WHO standards. To further the comparison, average SO2 levels in downtown Beijing are 16.8 ppb, which is 44 µg/m³. The worst pollution in Beijing comes in January, but even then, it's only 142 µg/m³.

Healthy people should not have too significant negative consequences, although Umhverfisstofnun is advising even healthy people to avoid strenuous activity outdoors. It is a much greater health concern for pollution-vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, young children, people with asthma or other breathing disorders, people with heart disease, etc. Umhverfisstofnun cautions them to avoid exerting themselves, and those that are on medication should consult with their doctors about potentially getting their prescriptions increased, as well as always having their medications on-hand. Residents are advised to pay close attention to pollution alerts for when conditions are the worst and to respond accordingly.

Here in Reykjavík we're breathing easy - at least for now. The predominant wind patterns blow the plume away from us - although sometimes it reverses. I have no breathing problems, but a few of my friends and my ex's children are in the vulnerable categories.

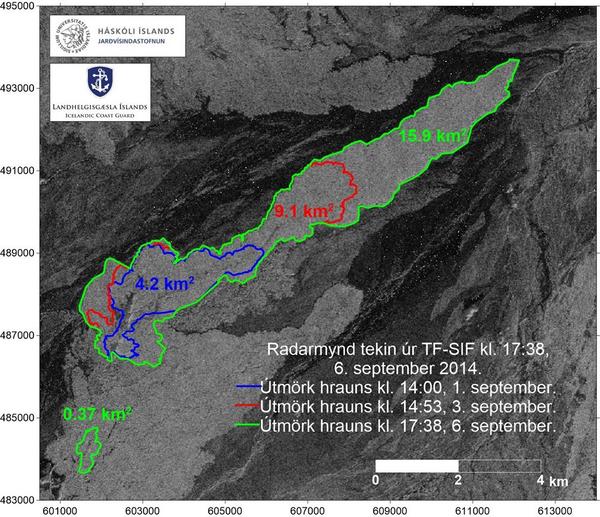

Meanwhile on the site of the eruption, things are consolidating. The number of active vents has dropped to two, or by some reports, just one. Yet total flow rates are higher than ever (excepting the brief initial outflow rate), 100-200m³/s (flow rates in previous days were reported at 100-150m³/s, and before that, 100m³/s).

This consolidation of fissure eruptions into a small set of craters is nothing unusual, and is part of their normal evolution. However, should pressure rise, new or old fissures can re-open, on the same site or elsewhere.

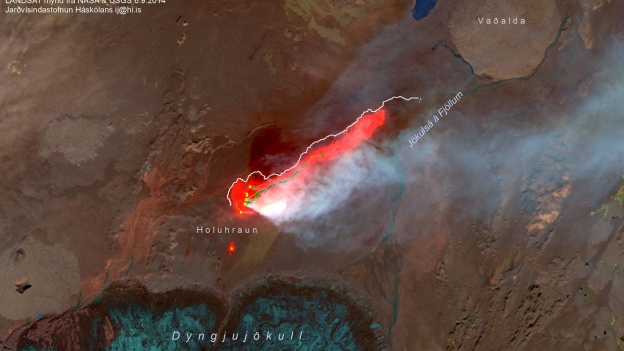

The longest tongue of lava is now flowing into the Jökulsár á Fjöllum, moving at a rate of 80-100 meters per hour (Pronunciation: "YUH-kihs-Our ow FYUH-tl-ihm"; the "tl" involves blocking airflow with the tongue then letting it burst to the sides). This river ("Glacial Rivers of the Mountains") starts as many separate branches feeding off the glacier Vatnajökull, which then consolidate into one of Iceland's largest rivers, racing over Dettifoss (most powerful water in Europe) and other falls, off into the arctic ocean. Here's a shot of the lava just arriving at the river:

So the river is dammed up by now, right? No, it's just flowing further to the east. The river channel here is several hundred meters wide, concentrated into a bunch of intertwined streams. And as the lava continues to advance, the river is going to continue to move further to the east, potentially out of its banks. But the further it has to detour around the lava, the longer it's going to be in contact with hot rock that has lava still flowing underneath. And eventually one could conceive that the contours of the landscape could force the river across the lava flow (for example, at Vaðalda), giving even more opportunity for the water to boil off.

Time will tell what happens. As it stands, however, effects on flow rate are minimal, and the data is not yet conclusive. I will continue to monitor the flow rate and temperature meters at Upptyppingar (25 kilometers downstream) for changes.

What about steam explosions? They're not expected today, but volcanologist Þoraldur Þórðarson says could happen tomorrow. On the other hand, Magnús Tumi says that he doesn't expect anything dramatic. The exact mechanism which leads to the formation of these "pseudocraters" is still debated, but it involves in one form or another lava flows stretching out over top of a deeply saturated ground but managing to trap the steam pressure. When it breaks free, it erupts steam and lava and leaves behind what looks just like a regular volcanic crater, but with no "roots" underneath. Iceland is one of the few places in the world where pseudocraters are common, but they have only been directly observed forming once in history, during the Fimmvörðuháls lava flows on Eyjafjallajökull. If they should form here it could be an excellent research opportunity for the science team.

Lastly, the caldera itself. The tremendous level of subsidence - which is in all likelihood not done - has seriously altered the nature of the glacier, according to Magnús Tumi. Ice now sinks down there and is locked in the depression, and may form new subglacial lakes. These can lock water under the glacier which can then be released during an eruption, which raises concerns of "seriously large jökulhlaup", according to the interview.

Vulcanologist Haraldur Sigurðsson suggests that the dropping of the top of the caldera could be, rather than due to loss of magma into the dike, a process where the top drops and magma flows up into the circular fissure left overhead, pushing out to the sides. He also comments that regardless of what's going on, there is a tremendously large amount of magma in Bárðarbunga's magma chamber, and activity could quite reasonably continue there for many years.

At this point, it's hard to know for sure exactly what's going on, and even harder what will happen. But Bárðarbunga keeps getting some of its biggest quakes yet.

What's going on is certainly fascinating, and of course people want to visit the site of the eruption on Holuhraun. The roads have been re-opened... to scientists and the media, and even then only with special permission. The site is still simply too dangerous for the general public. Right now, the only way for the public to see it in person is with $2000 per person helicopter tours. Which of course prices is out of most peoples' budgets.

But at least we've got Míla. And pictures. :)

The eruption cloud is visible from Mývatn even during the day at times:

Fresh, steaming lava:

Snow? Strange.

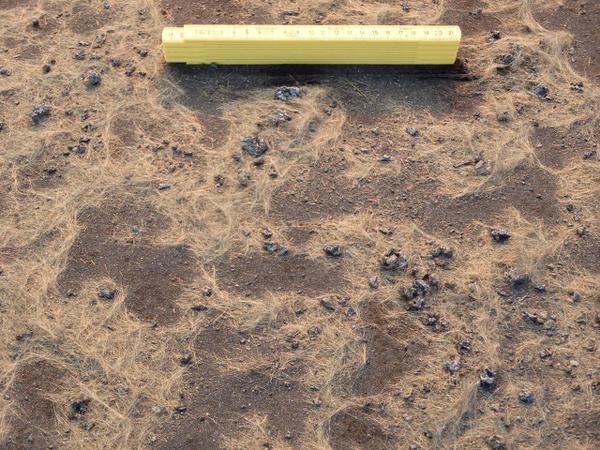

Anyone know what this is all over the ground?

If you guessed nornahár ("Witches Hair"), or in English, "Pele's Hair", you're right. Here's a closeup:

It's made by flying molten lava being stretched by air currents into thin strands, and is exactly the same material as the basalt fiber insulation you may have seen in hardware stores.

A recent map:

Lastly, one simple video of the day, focused on the plume: