Everyone "knows" that Charles Lindbergh in the Spirit of St Louis was the first person to make a nonstop airplane flight across the Atlantic Ocean, in 1927.

And everyone is wrong.

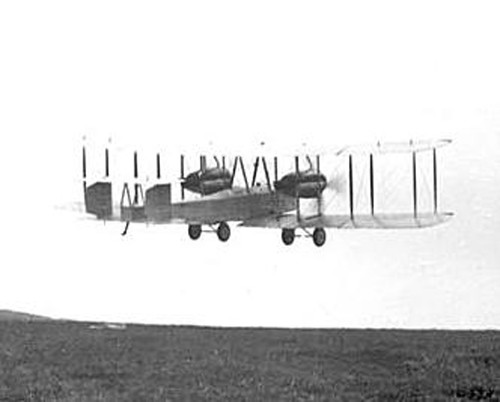

William Alcock and Arthur Brown take off in their Vickers-Vimy airplane for the first nonstop transatlantic flight.

In 1913, ten years after the Wright Brothers made their first flight, aviation was still in its infancy. Louis Bleriot had made the first flight across the English Channel and had demonstrated the potential of air travel, but for the most part airplanes were still rickety things that could only make short hops, and often crashed.

To encourage technical innovation in the field of aeronautics, the owner of the London Daily Mail newspaper, Lord Northcliffe, offered a prize of 10,000 pounds (over $1 million in today’s money) to any pilot who could fly an airplane from any point in North America across the Atlantic Ocean to any point in Ireland or Great Britain, within 72 hours. Announced on April 1, 1913, it was no April Fool’s joke. As Northcliffe well knew, no airplane was even remotely capable of the trip at that time—the purpose of the prize was to spur new improvements in air travel that would make it possible in the future.

In August 1914, the First World War broke out, and Northcliffe temporarily suspended the prize. When the “Atlantic Challenge” was renewed after the Armistice in November 1918, the Great War had produced the enormous technical advances in aviation necessary for the task, and a number of teams, sponsored by several different aircraft manufacturers, set out to win the prize.

By May 1919, four aircraft and their crews were gathered in St John’s, Newfoundland, ready to attempt the flight. The first to take off, on May 18, was Australian pilot Harry Hawker and his American navigator Mackenzie Grieve, in a twin-engine Sopwith. About halfway across the Atlantic, they had a radiator blockage in one of their engines, forcing them to ditch at sea. It was six days before the world learned that they had been rescued by a passing steamship.

A few days earlier, another team from the Martinsyde Company had crashed on takeoff.

During this time, the first transatlantic flight had already been accomplished: the US Navy seaplane NC-4, piloted by Lt Commander Albert Read, had flown from the Naval Air Station at Rockaway, New York, to the port of Plymouth in England, making six stops over 23 days. Because it had taken longer than 72 hours, it was not eligible for the Daily Mail prize, but the NC-4’s flight demonstrated that a nonstop flight was imminent.

Two teams remained in contention for the Atlantic Challenge: a four-engine Handley-Page V/1500 “Berlin Bomber” biplane piloted by Admiral Mark Kerr, and a twin-engine Vickers piloted by John William Alcock and navigated by Arthur Whitten Brown.

The Vickers FB-27 Vimy had been developed in 1917 but entered production too late to participate in the First World War. With a wingspan of 67 feet, it was powered by two 12-cylinder Rolls-Royce engines with 360 horsepower each. In 1919 the Vimy was being produced by the RAF as a long-range bomber carrying a crew of three and one ton of bombs, and as a torpedo-armed coastal patrol plane. The Vickers company also hoped to develop a commercial version into a long-distance freight and passenger carrier.

Both Alcock and Brown were war veterans. Alcock, a Distinguished Flying Cross winner, had flown Navy bombers in Greece and Turkey, where he had been forced down by engine failure during a raid and spent the rest of the war in a Turkish POW camp. Brown was an observer/gunner for reconnaissance planes in France, and was shot down and captured. Severely wounded, he was turned over by the Germans to the Red Cross, and after being returned to England for treatment he became a flight instructor.

After arriving in Newfoundland and testing the newly-reassembled Vickers, Alcock and Brown were delayed a few days by a broken axle and trouble with an additive in their gasoline. By June 14 they were ready again, but that morning high winds were whipping the field. Alcock at first decided to delay the takeoff until the next day, but after hearing that Kerr was planning to try his own flight later that afternoon, Alcock and Brown decided to leave right away. As a curious crowd looked on, the Vickers-Vimy was fueled, some mail bags were loaded, and after making last-minute repairs to a wind-damaged fuel pipe, the Vimy rolled down the grass strip, lifted into the air, and set off for Ireland.

They encountered difficulties almost immediately. The radio malfunctioned, preventing them from being able to transmit. Over the Atlantic they hit bad weather, with snow and ice coating their plane and interfering with their control surfaces. Brown had to climb out of the cockpit to scrape away ice. Part of their exhaust system broke off, their radiator began icing up, and their fuel gauges froze over with snow. At one point, socked in by clouds and unable to see the horizon, Alcock became disoriented and, unable to tell which way was “up”, found himself in a sharply-banked diving turn when he emerged from the cloud layer only a hundred feet above the ocean surface, and leveled out before the plane crashed.

It wasn’t until they spotted two small islands off the Irish coast through a gap in the clouds that they were finally sure where they were, and knew they had been successful in crossing the Atlantic. As the clouds cleared over land, Alcock and Brown found themselves circling over the small Irish village of Clifden.

It being a Sunday, the entire town was in church, and did not know anything was unusual until they heard the plane’s engines as the Vimy descended for a landing. Alcock had selected a landing spot that looked like a flat field. In reality, though, it was a shallow bog, and as the Vimy’s wheels touched down and rolled, they sank into the mud and stuck, and the plane nosed over and buried both propellers in the soggy peat. It was an ignominious ending to a triumphant flight. They had covered almost 1900 miles in 15 hours and 57 minutes.

Alcock and Brown climbed out unhurt and announced to the gathering crowd of villagers that they had just come from Canada. From a Marconi radio station in the village, the word went out—the Atlantic Challenge had been met. The Daily Mail, who was supposed to have the exclusive newspaper story of the flight, rushed its reporter from the nearby town of Galway—but he had already been beaten by the editor of the Connacht Tribune, who interviewed the two aviators and put the story out by wireless. (As it turned out, the Daily Mail was scooped twice: the landing had been made on a Sunday, and while the Daily Mail did not have a Sunday edition, the competing London Express did, and ran the story first.)

Within hours, congratulatory telegrams began arriving from all over the world. Alcock and Brown were feted by city and local officials in Clifden, Galway, Dublin, Manchester and London. They were presented with the 10,000-pound Daily Mail prize by the British Secretary of State for War, Winston Churchill, and the next day both fliers were knighted by King George V at Buckingham Palace.

The Vimy was taken apart and carried back to England, where the Vickers company refurbished the plane and donated it to the Museum of Science in London. Just three days later, in December 1919, Alcock was killed in a crash as he was delivering the new Vickers Viking seaplane to the Paris Air Show. His partner Brown, who never flew again, died in 1948.

In 1927, Charles Lindbergh won the Orteig Prize for the first nonstop flight from New York to Paris. Although Lindbergh was the first person to fly the Atlantic solo (which had not been a requirement for the Orteig Prize—he had done it simply to save weight), he was actually the 19th person to cross the Atlantic in an airplane. Today, Charles Lindbergh is the most famous pilot in history, while John William Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown have been all but forgotten.