The Plateau Culture Area is the area between the Cascade Mountains and the Rocky Mountains in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, British Columbia, and Western Montana. From north to south it runs from the Fraser River in the north to the Blue Mountains in the south. Much of the area is classified as semi-arid. Part of it is mountainous with pine forests in the higher elevations.

While much of the Plateau Culture Area constitutes a dry region characterized by a sagebrush-Juniper steppe area with pine forests at the higher levels, there are portions of the area which do not fit this description. In the northern portion of the Plateau Culture Area, there is a temperate rainforest with higher precipitation.

The shaded area on the map shown above designates the Plateau Culture Area.

The shaded area on the map shown above designates the Plateau Culture Area.

The idea of an Indian reservation was first introduced to the Indian nations of the Plateau culture area in 1855 when the United States government began imposing treaties on the Plateau Indian nations. From the government's perspective, these treaties were seen as a way of obtaining large tracts of land which would be secured for non-Indian settlers. Historian Kent Richards, in his short biography of Governor Isaac Stevens in Shadows of Our Ancestors: Readings in the History of Klallam-White Relations, writes:

“In conducting the treaty sessions, he did not think it necessary to pay much heed to Indian complaints that traditional customs, habits, superstitions, or religious mores would be violated by the treaties. After all, the long-term consequence of the treaties, in Stevens’ view, was to replace the traditional pattern of Indian life with the superior white civilization.”

In some instances, Governor Stevens appointed the tribal chiefs who were to sign for their people. In general, the treaties call for tribes being restricted to certain areas (reservations) and it was not uncommon for tribes with totally different languages and cultures to be grouped together. For example, 14 different tribes and bands were confederated into the Yakama Indian Nation at the Walla Walla Treaty Council. At the Wasco Treaty County, the United States combined several western Columbia Sahaptin bands onto the Warm Springs Reservation.

Historian Robert Utley, in his book The Indian Frontier of the American West 1846-1890, writes of Governor Stevens’ negotiating methods:

“His methods featured fast talk, bluster, and intimidation, and when he finished he had stampeded virtually all the groups of the territory into signing treaties.”

According to the Nez Perce Tribe, in their book Treaties: Nez Perce Perspectives:

“Stevens intentionally neglected to tell the Indians that he had specifically selected lands for their reservations that no white man yet wanted, and, perhaps most importantly, he made no mention of his desire to secure land for the railroad.”

On the reservations, Indians were supposed to become English-speaking, Christian farmers, just like the other immigrants to the United States. Since Indians were not American citizens, nor could they become American citizens, they had few civil rights and reservations were sometimes run like large prisons.

The High Plains Museum, just south of Bend, Oregon, has a display about reservation life.

According to the Museum display:

“For many Plateau people, reservation life in the 1800s was a severe shock. Although treaties guaranteed them access to traditional hunting, fishing and gathering sites, restrictive policies and governmental Indian agents discouraged traveling off reservations. Unprepared for the rapid change, some Plateau Indians relied on food, clothing, and housing promised by the federal government as they made the adjustment to the new life. Others made the change quickly by turning to cattle ranching, farming or commercial fishing.”

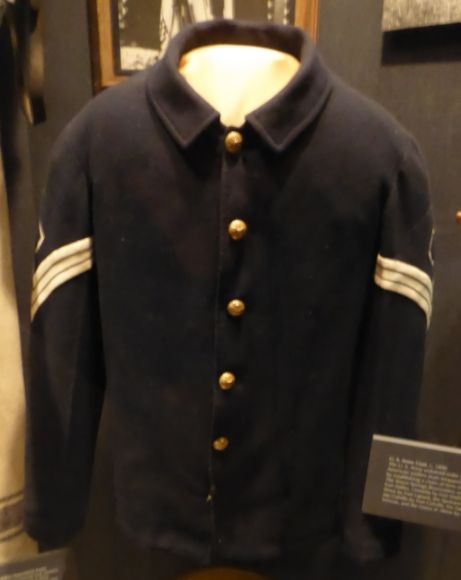

Even though the Indian Bureau was under the Department of the Interior, the 1890 military uniform shown above symbolizes the continuing role of the army in regulating Indian life.

Even though the Indian Bureau was under the Department of the Interior, the 1890 military uniform shown above symbolizes the continuing role of the army in regulating Indian life.

According to the Museum display:

“The U.S. Army enforced law and order and tried to prevent American settlers from trespassing on Indian lands by establishing a chain of forts near reservations. The Warm Spring Reservation was monitored by Fort Dalles, Umatilla by Fort Walla Walla, the Nez Perce by Fort Lapwai, the Spokane by Fort Spokane, the Colville by Fort Colville, the Yakama by Fort Simcoe, and the Coeur d’Alene by Fort Sherman.”

During the reservation period, Indians had to have written permission to leave the reservation. When courts ruled that Indians had the right to leave the reservation, these rulings were ignored, some say deliberately suppressed, by the Indian Bureau.

By the last two decades of the nineteenth century, government policies focused on making Indians into Christian, English-speaking farmers by breaking reservations into allotments—allotments which were small enough to guarantee failure. The allotment concept ignored economic, cultural, and ecological reality and focused totally on ideology.

Stereotypes

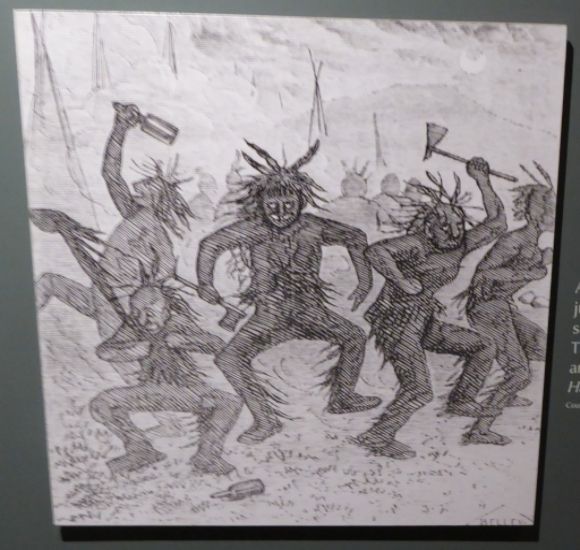

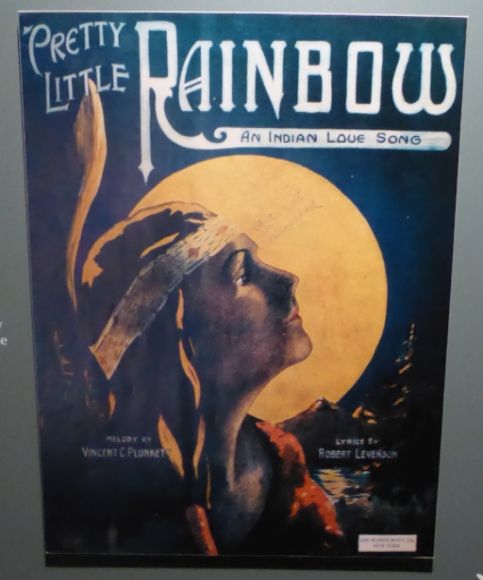

According to the Museum display:

“From the days of colonization, Indians were often labeled as violent, noble, or drunken and lazy. As Indian populations declined from war and disease in the nineteenth century, the image of the ‘vanishing Indian” joined the list. Like all stereotypes, those imposed on Native Americans hide the true people.”

The common stereotype of the vanishing Indian is shown above.

The common stereotype of the vanishing Indian is shown above.

The stereotype of the Indian as the violent savage is shown above. This image, which appeared in Harper’s Weekly, is a depiction of Chief Joseph at the start of the Nez Perce War.

The stereotype of the Indian as the violent savage is shown above. This image, which appeared in Harper’s Weekly, is a depiction of Chief Joseph at the start of the Nez Perce War.

Shown above is an example of the Noble Savage stereotype in the form of an idealized “Indian princess” image. The Noble Savage stereotype sees Indians as living in pure harmony with nature.

Shown above is an example of the Noble Savage stereotype in the form of an idealized “Indian princess” image. The Noble Savage stereotype sees Indians as living in pure harmony with nature.

The Cigar Store Indian is another common stereotype.

The Cigar Store Indian is another common stereotype.

Housing

Shown above is a reservation tipi from the Coeur d’Alene Reservation in Idaho. This is from 1963.

Shown above is a reservation tipi from the Coeur d’Alene Reservation in Idaho. This is from 1963.

Plateau Indians continued to put up tipis when they moved into the more traditional European-style rectangular houses. According to the Museum display:

“Today, some still use them to house visiting guests, or to sleep in during hot summer months. Often tipis are taken along for shelter when they attend celebrations, harvest plants, fish or hunt. This tipi’s repairs and weathering testify to a Plateau family’s dedication to a traditional, yet practical architectural form.”

Shown above is the inside of the tipi.

Shown above is the inside of the tipi.

Shown above is the area between the tipi and the reservation house.

Shown above is the area between the tipi and the reservation house.

Shown above is the front of the reservation house.

Shown above is the front of the reservation house.

Shown above is the inside of the reservation house.

Shown above is the inside of the reservation house.

According to the Museum display:

“Within the walls of reservation homes like this one, Plateau grandparents and parents passed their heritage to new generations. In 1963, it was common for extended families to still share single dwellings of this type. All the objects in this house came from Native American families.”

Shown above is the kitchen area.

Shown above is the kitchen area.

Shown above is the “living” room area of the house which also functioned as a sleeping area. The TV set plays episodes from The Lone Ranger in which Mohawk actor Jay Silverheels played Tonto.

Shown above is the “living” room area of the house which also functioned as a sleeping area. The TV set plays episodes from The Lone Ranger in which Mohawk actor Jay Silverheels played Tonto.

Shown above is a modern electric refrigerator.

Shown above is a modern electric refrigerator.

Shown above is a small ice box.

Shown above is a small ice box.

Shown above is an outside propane stove.

Shown above is an outside propane stove.

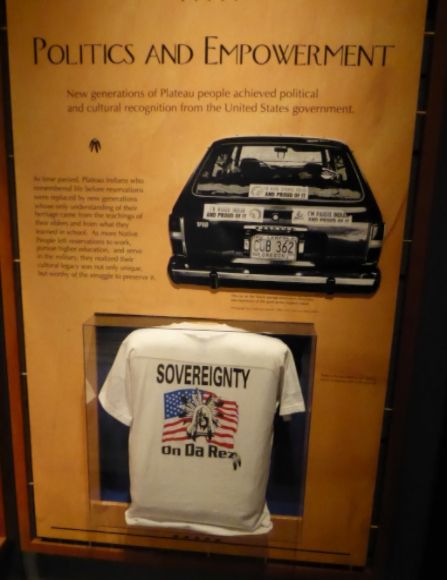

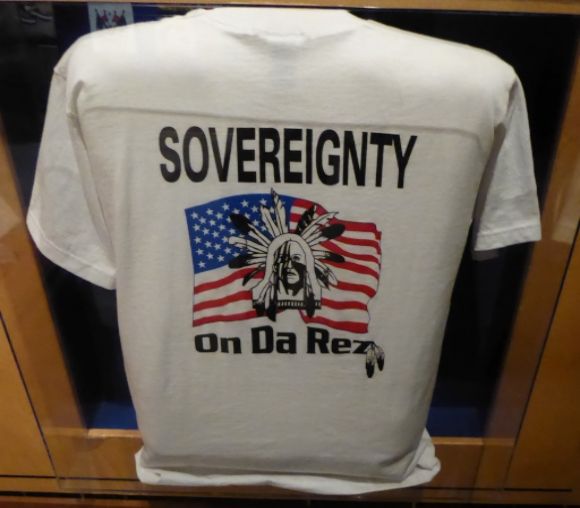

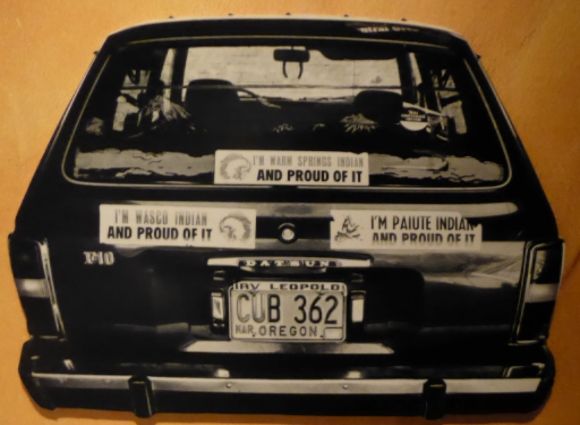

Politics

According to the Museum display:

“As time passed, Plateau Indians who remembered life before reservations were replaced by new generations whose only understanding of their heritage came from the teachings of their elders and from what they learned in school. As more Native People left reservations to work, pursue higher education, and serve in the military, they realized their cultural legacy was not only unique, but worthy of the struggle to preserve it.”

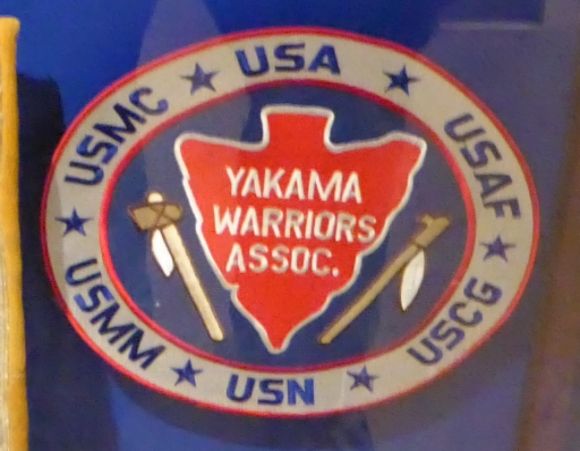

The World Wars

Plateau Indians served in World War I, World War II, and all other wars since.

Indians 101

Indians 101 is a series exploring American Indians cultures, histories, and current concerns. More about Plateau Indians from this series:

Indians 101: Plateau Indian Basket Hats and Trinket Baskets (Photo Diary)

Indians 101: Plateau Containers in the Maryhill Museum (Photo Diary)

Indians 101: The Horse and the Plateau Indians

Indians 101: Kootenai Fishing and Hunting

Indians 101: Plateau Indian Names

Indians 101: Camas, a Traditional Native Food