During the nineteenth century, the United States aggressively pursued a policy of manifest destiny to spread out between the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans. The term “manifest destiny” first appeared in 1845 in the New York Democratic Review. The newspaper declared:

“our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.”

Free lance writer Nancy Wood, in her book When Buffalo Free the Mountains: The Survival of America’s Ute Indians, says:

“Manifest Destiny meant simply that the white race was ordained by God to rule all of America and that included the Indians, believed to be an inferior race deserving of extinction.”

In The Battle of the Big Hole: The Story of the Landmark Battle of the 1877 Nez Perce War, Aubrey Haines writes:

“It was a term used to describe a belief in the inevitability of the territorial expansion of the United States. Those who preached manifest destiny maintained that the United States, through the superiority of its institutions, resources, and rapidly growing population, should rule all of North America.”

In their chapter on manifest destiny in North American Indian Wars, James Davidson, William Gienapp, Christine Heyrman, Mark Lytle, and Michael Stoff write:

“Many Americans had long believed that their country had a special, even divine mission. The Protestant version of this conviction could be traced back to John Winthrop, who assured his fellow Puritans that God intended them to build a model ‘city upon a hill’ for the rest of the world to emulate.”

In his book The Bitter Waters of Medicine Creek: A Tragic Clash Between White and Native America, Richard Kluger describes manifest destiny this way:

“God had assigned the American people, robust and pure of heart, to spread the gospel of liberty and democracy around the earth—well, certainly across all of North America—and prosperity and happiness would follow.”

The High Desert Museum in Bend, Oregon, has a gallery which takes visitors on a journey through some of the most dramatic periods in the High Desert. According to the Museum display:

“Thousands of years ago, more than one hundred Native American tribes inhabited the High Desert. During the early 1800s, newcomers began arriving—starting with fur traders and continuing with homesteaders through the early 1900s. A diverse array of immigrants added their stories to the region’s history.”

The Oregon Trail

During the two decades following 1843, more than 50,000 emigrants would follow the 2,000 miles of the Oregon Trail from Missouri to Oregon. Publicists billed Oregon as a land of abundance, the Garden of the World. According to the Museum display:

“By the 1840s thousands of emigrants embarked on the trails west each year, inspired by the desire for land and a new start. After crossing the Rocky Mountains, they entered the High Desert. Their trails traversed an arid landscape. Whether they continued on the Oregon Trail, turned off on the California Trail, or chose a cutoff like the Applegate Trail, it was a tremendously difficult stage of their 2,000-mile journey.”

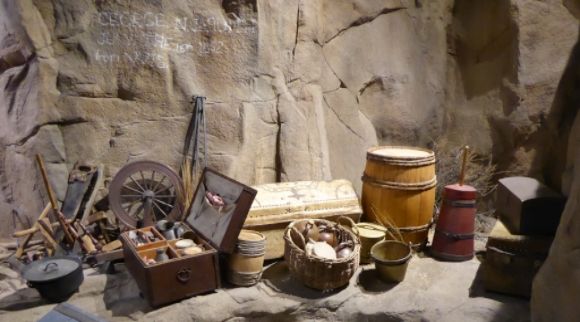

The emigrants brought with them all of the things they thought they mind need to start life anew.

The emigrants brought with them all of the things they thought they mind need to start life anew.

It was not uncommon for the wagons to break down and require repair.

It was not uncommon for the wagons to break down and require repair.

Mapmakers

According to the Museum display:

“It was the highly trained mapmakers of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers who first documented the region’s resources. John C. Fremont produced the first accurate map of the Oregon Trail, and was the first explorer to define the Great Basin. The corps’ Pacific Railroad Survey of the 1850s was a virtual illustrated catalog of the Far West landscape, wildlife and resources.”

Mining

Mineral resources in the High Desert were extracted with hard rock or lode mining and with placer mining. Concerning hard rock mining, the Museum display states:

“Miners drilled and blasted mines that could reach over a mile down. The era brought in inventions and technologies of the Industrial Revolution to the High Desert: steam engines powered hoists and refining machinery, and massive pumps removed millions of gallons of groundwater.”

While the High Desert Museum has a realistic diorama of hard rock mining, the low light levels (emulating the lighting in the mines) did not allow for photography.

Concerning placer mining, the Museum display states:

“Retrieving gold from the region’s waterways was termed placer mining. Skilled and fortunate miners used water to separate the heavier gold from lighter sand and gravel. The ragged communities of tents and cabins often lasted only as long as the gold, then disappeared.”

Museums 101

Museums 101 is a series providing photo tours of museum displays from different museums. More from the High Desert Museum:

Museums 101: Buckaroos (Photo Diary)

Museums 101: Animal Sculptures (Photo Diary)

Museums 101: Settlers in the High Desert (Photo Diary)

Museums 101: Ranch and Sawmill (Photo Diary)