Mesoamerica is the area from Mexico south through Panama. In this geographic area, a number of complex cultures emerged with subsistence patterns based on agriculture and wide-spreading trading networks. Like the ancient civilizations in other parts of the world, such as Mesopotamia, China, and Egypt, the Mesoamerican civilizations were characterized by cities, hierarchical governments, and writing.

In their book Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs, Michael Coe and Rex Koontz report:

“By the Classic period, literacy may have been pan-Mesoamerican, although probably only the Maya and to a lesser extent the Zapotecs had fully developed hieroglyphic scripts—that is, writing systems which recorded the spoken language. Although no books have survived from the Classic into our days, we have every reason to believe that many people possessed them.”

The Classic period in Mesoamerica is usually considered the period from 250 CE to 900 CE. Regarding the designation “Classic,” Michael Coe and Rex Koontz write:

“This era of florescence is called the Classic, and it is at this time that the people of Mexico built civilizations that can bear comparison with those of other parts of the globe. With justification, the Classic is thought of as the Golden Age, when the seeds that were planted during the Preclassic reached their fruition.”

With regard to writing among the Maya, Bruce Trigger, in his book Understanding Early Civilizations: A Comparative Study, writes:

“The Classic Maya also produced books, written on bark cloth or parchment. No book survives, however, from the Classic period in legible condition, and the few later ones that have been preserved deal exclusively with divination. It is unknown whether the Classic Maya used writing to record administrative data, historical chronicles, or religious texts.”

While books often do not survive the ravages of time, stone does and thus much of the ancient Mesoamerican writing known today comes from stone inscriptions. Numerous examples of this type of writing, which often commemorate kings and royalty, are found in the ancient Maya cities such as Tikal, Copan, Palenque, Bonampak, and Chichén Itzá.

The stela—a slab or stone monument—was decorated with carvings, inscriptions, and dates. In addition to being carved the stelae were often painted. The stelae served as ceremonial objects and as a way to commemorate both important religious and governmental officials. A stela was often erected in a plaza, usually in front of a temple.

One of the earliest representations of human sacrifice in Mesoamerica is found in Stela 21 at the Mayan site of Iztapa in Chiapas, Mexico. The stela was carved between 100 BCE and 100 CE. In his book The Complete Illustrated History: Aztec and Maya, Charles Phillips reports:

“The pillar depicts a standing figure holding the head of a newly decapitated victim, whose lifeblood pours forth in long scrolls from the head and the prostrate body, while in the background, a ruler or noble passes by in a sedan chair carried by two porters.”

The stelae often commemorate the ascension of new kings. Stela 4 at Tikal, for example shows the ascension of King Curl Nose in 378 CE. In some instances, there are two stelae: one representing the king and the other the queen. Stelae 28 and 29 at Calakmul, for example, were raised to the city’s second king in 623 CE.

Stelae may also commemorate military victories. At Quiriguá, Stela E, commemorates the 771 CE victory of King Cauac Sky over the city of Copán. This stela, by the way, is 35 feet tall and weighs about 65 tons.

In their Encyclopedia of Ancient Mesoamerica, Margaret Bunson and Stephen Bunson report:

“Some stelae are full-faced figures, standing 30 feet high. At first only one side of the stelae were carved, then details were engraved on all sides.”

Many of the stelae are dated as the Mesoamerican civilizations had an accurate calendar system. This allows archaeologists to accurately date certain events. Margaret Bunson and Stephen Bunson report:

“These monuments, carrying specific information, provide details about the decline of the Maya realm in some regions.”

By about 830 CE, the use of stelae by the Maya was in decline and the last known stela carries a date of 909 CE.

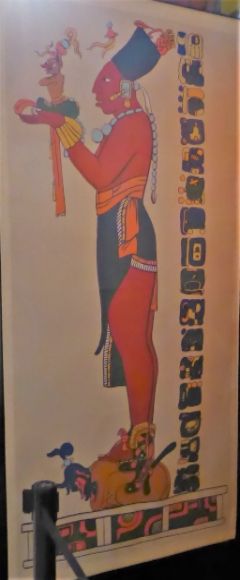

Shown above is a full-size depiction of a painted stela which is on display in the San Bernardino County Museum (in California).

Shown above is a full-size depiction of a painted stela which is on display in the San Bernardino County Museum (in California).

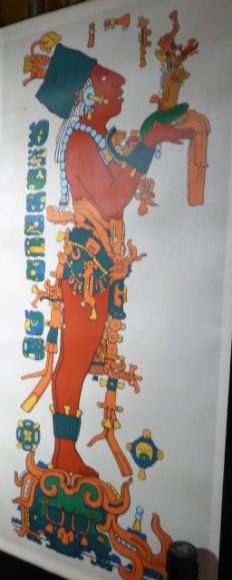

Shown above is a full-size depiction of a painted stela which is on display in the San Bernardino County Museum.

Shown above is a full-size depiction of a painted stela which is on display in the San Bernardino County Museum.

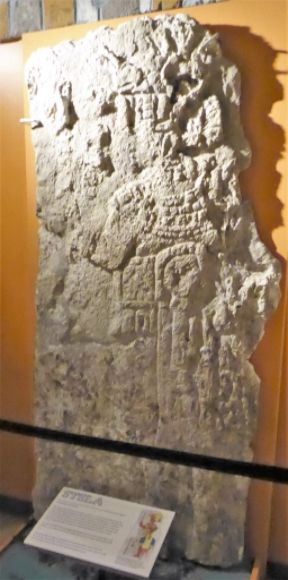

Shown above is a stela which is on display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California. This stela, from the Guatemalan Department of Peten, dates stylistically to the Middle to Late Classic periods.

Shown above is a stela which is on display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California. This stela, from the Guatemalan Department of Peten, dates stylistically to the Middle to Late Classic periods.

With regard to the stela displayed at the San Bernardino County Museum, the Museum display states:

“This large panel, which stands nearly six feet tall, is creamy white limestone and depicts a kingly figure standing frontally with his head to the right side. He holds a staff or spear in his right hand and wears a jaguar headdress, bead necklaces, and bead bracelets. His short skirt has a central loincloth that hangs to his knees. At his waist he wears a wide belt decorated with a central human head medallion. The deep bas relief carving means that the figure is recognizable although it is quite eroded.”

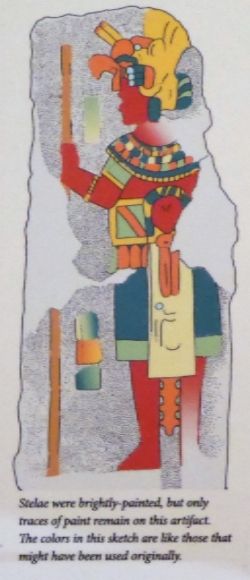

This shows what the stela would look like with its paint.

This shows what the stela would look like with its paint.

The stela on display at the San Bernardino County Museum is considered a Guatemalan national treasure and it is displayed at this museum with the knowledge and permission of the Guatemalan government.

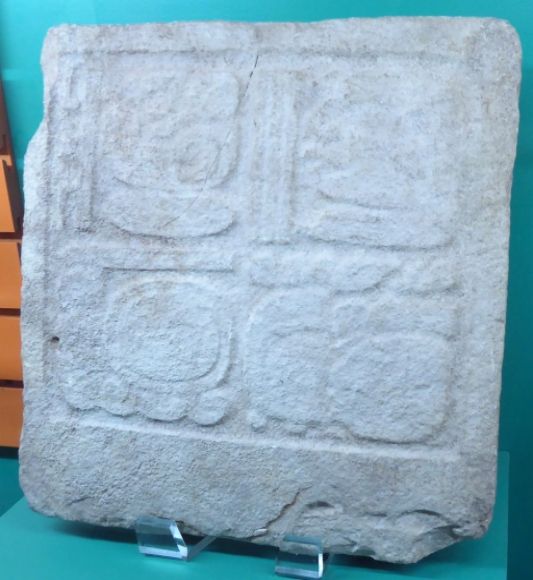

The stela shown above contains a series of glyphs—a form of writing—from Yucatan. The glyphs date the panel to December 23, 732 CE.

The stela shown above contains a series of glyphs—a form of writing—from Yucatan. The glyphs date the panel to December 23, 732 CE.

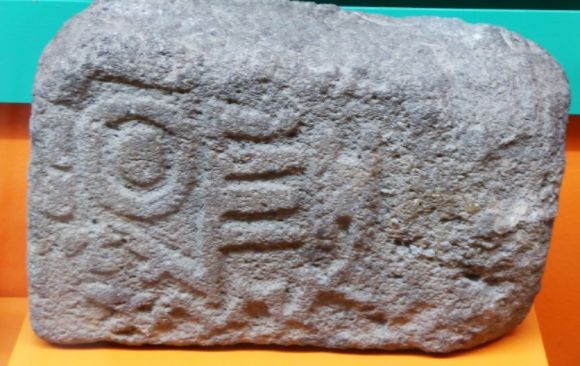

Shown above is a carved stone with glyphs, probably Aztec.

Shown above is a carved stone with glyphs, probably Aztec.