Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) is generally considered to be one of the founders of modern sculpture. While traditional sculpture prior to Rodin tended to be decorative, formulaic, or thematic, Rodin portrayed the human body with realism and celebrated individual character and physical features. Rodin was considered a naturalist who focused on character and emotion rather than on monumental expression. During his life, his works were often criticized and were somewhat controversial.

While Rodin showed artistic talent at a young age, he was a poor student. He attended the Ecolé Impériale Spéciale de Dessin et de Mathématique where he learned modeling and drawing. He applied to get in to the noted Ecole des Beaux-Arts and was rejected three times. Humiliated by this failure, Rodin went to work for commercial decorators and sculptors. However, he had a compulsion to sculpt and opened his own studio.

Rodin spent six years in Belgium during which time he journeyed to Italy to visit the fourth Michelangelo centennial. Rodin began to depart from the accepted style of French sculpture, focusing on investigating the human form as a vehicle to express human emotion.

The Maryhill Museum of Art near Goldendale, Washington, has a collection of Rodin’s works. According to the Museum display:

“The Auguste Rodin collection at Maryhill Museum is a lasting tribute to the strong bond of friendship, respect, and admiration that existed between Rodin and Loïe Fuller, an innovative American dancer who performed in Paris at the turn of the century.”

Shown above is Young Girl With Flowers in Her Hair which was done about 1868.

Shown above is Young Girl With Flowers in Her Hair which was done about 1868.

Shown above is Embracing Children which was done about 1881.

Shown above is Embracing Children which was done about 1881.

Shown above is Crying Lion which was done about 1881. Rodin rarely sculpted animals and his animals usually express human emotions, such as the pain, sorrow, and loneliness seen in this terra cotta lion.

Shown above is Crying Lion which was done about 1881. Rodin rarely sculpted animals and his animals usually express human emotions, such as the pain, sorrow, and loneliness seen in this terra cotta lion.

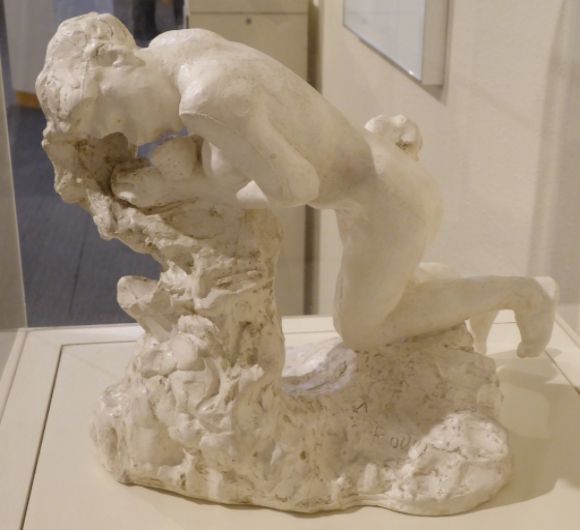

Shown above is The Minotaur, a plaster piece done about 1886.

Shown above is The Minotaur, a plaster piece done about 1886.

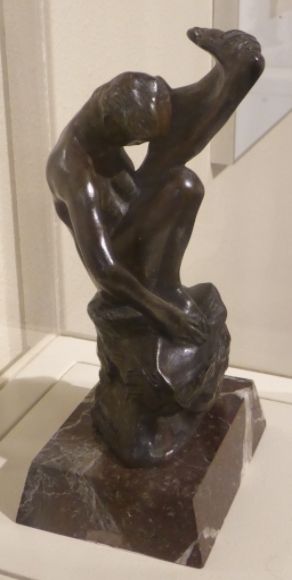

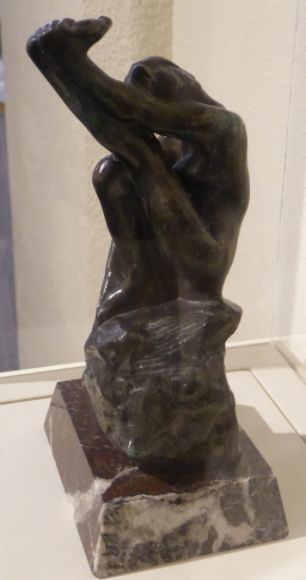

Shown above is The Minotaur, a bronze piece done about 1886.

Shown above is The Minotaur, a bronze piece done about 1886.

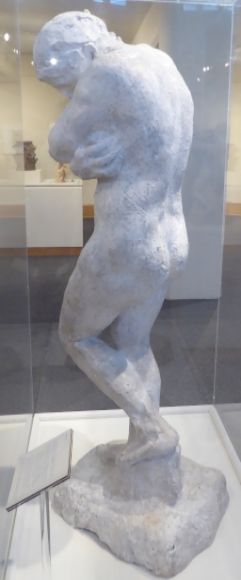

Shown above are three views of Eve, a plaster created in 1881.

Shown above are three views of Eve, a plaster created in 1881.

Concerning the Italian model used for Eve, Rodin would later write:

“Without knowing why, I saw my model changing. I modified my contours naively following the successive transformations of every-amplifying forms. One day, I learned that she was pregnant; then I understood. The contours of the belly had hardly changed; but you can see with what sincerity I copied nature in looking at the muscles of the loins and sides.”

Shown above are two views of I Am Beautiful, a plaster created about 1881-1882.

Shown above are two views of I Am Beautiful, a plaster created about 1881-1882.

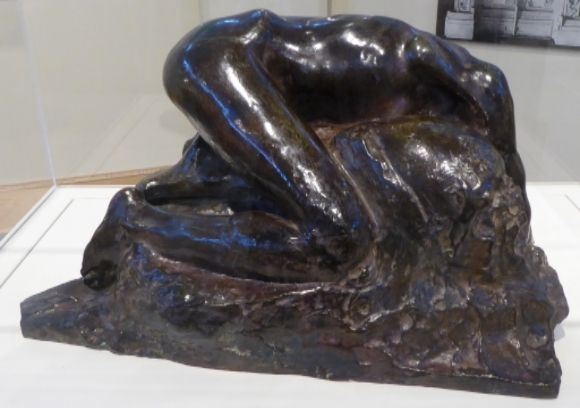

Shown above are two views of Danaïd, a bronze created about 1884-1885.

Shown above are two views of Danaïd, a bronze created about 1884-1885.

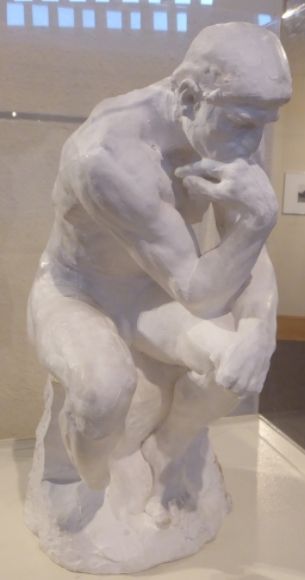

Shown above is The Thinker which was created in 1880. This is probably Rodin’s most famous work.

Shown above is The Thinker which was created in 1880. This is probably Rodin’s most famous work.

Shown above are two views of First Funeral, a bronze created about 1900.

Shown above are two views of First Funeral, a bronze created about 1900.

Shown above are two views of Youth Triumphant, a bronze created in 1894. This was one of the first works that Rodin had reproduced commercially.

Shown above are two views of Youth Triumphant, a bronze created in 1894. This was one of the first works that Rodin had reproduced commercially.

Shown above is Head of Balzac, a bronze created in 1897.

Shown above is Head of Balzac, a bronze created in 1897.

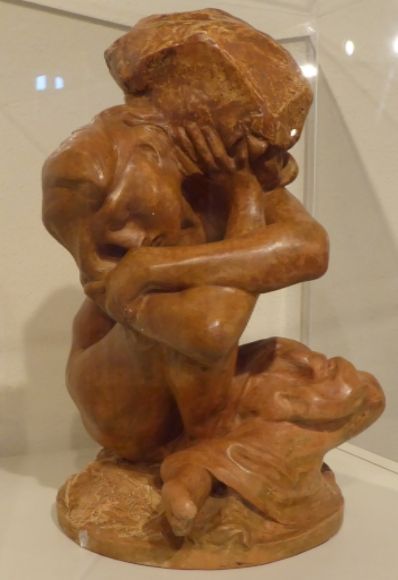

Shown above is Fallen Caryatid Bearing Her Stone, a bronze created about 1881.

Shown above is Fallen Caryatid Bearing Her Stone, a bronze created about 1881.

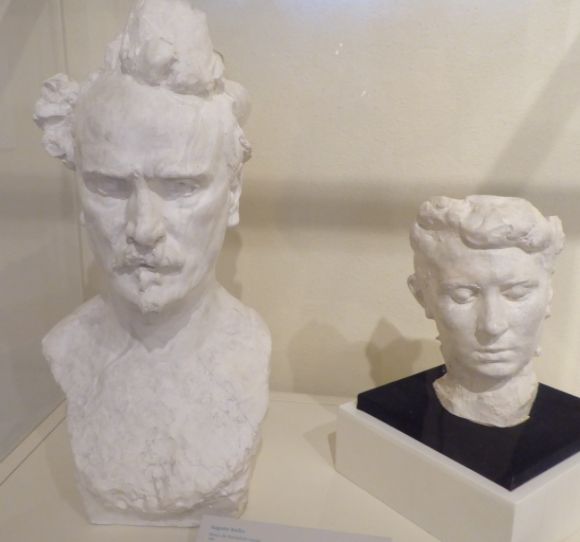

Shown above Henri de Rochefort-Luçay (left) and Mask of Madame Rodin (right). The Marquis Henri de Rochefort-Luçay (1831-1913) was a famous journalist. This plaster was created in 1891. Rodin met Rose Beuret (1844-1917) in 1864 and she bore his only child, a son. The couple were married in 1917, two weeks before her death.

Shown above Henri de Rochefort-Luçay (left) and Mask of Madame Rodin (right). The Marquis Henri de Rochefort-Luçay (1831-1913) was a famous journalist. This plaster was created in 1891. Rodin met Rose Beuret (1844-1917) in 1864 and she bore his only child, a son. The couple were married in 1917, two weeks before her death.

Shown above is Polyphemus, a plaster created in 1888.

Shown above is Polyphemus, a plaster created in 1888.

Shown above is Sorrow, a plaster created in 1887.

Shown above is Sorrow, a plaster created in 1887.

Shown above are three views of Despair, a bronze created about 1880.

Shown above are three views of Despair, a bronze created about 1880.

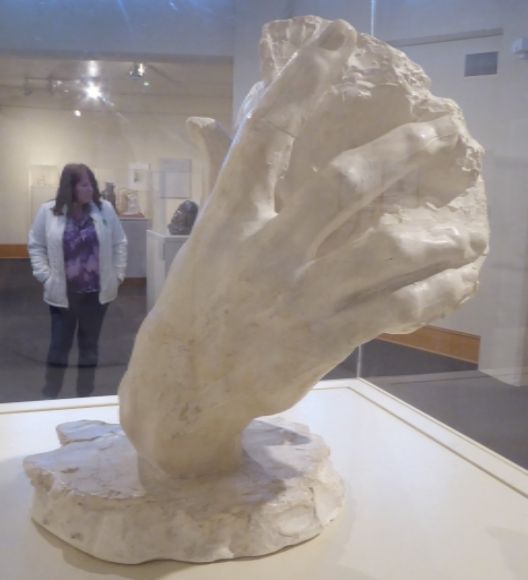

Shown above are two views of The Hand of God, a plaster created in 1898.

Shown above are two views of The Hand of God, a plaster created in 1898.

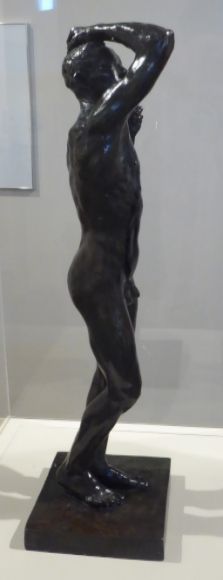

Shown above are three views of The Age of Bronze, a bronze created in 1875-1876. This became one of Rodin’s more popular pieces and was reproduced in various sizes.

Shown above are three views of The Age of Bronze, a bronze created in 1875-1876. This became one of Rodin’s more popular pieces and was reproduced in various sizes.

The Museum display reports:

“The work was immediately criticized for its vague subject matter. Worse, Rodin was accused of surmoulage, or casting directly from the live model. He was eventually exonerated and the French government commissioned a bronze cast.”

Fragments

While the academic tradition of the nineteenth century viewed fragmentary objects are incomplete, imperfect, and not works of art, Rodin embraced the fragment as a complete and independent work of art. According to the Museum display:

“Rodin’s critics viewed his use of partial figures as morbid, ugly, and in violation of established ethics.”

Rodin, however, continued to experiment with fragments and made casts of heads, torsos, arms, legs, hands, and feet with which he created new figures. He considered fragments to be whole and aesthetically beautiful in their own right.

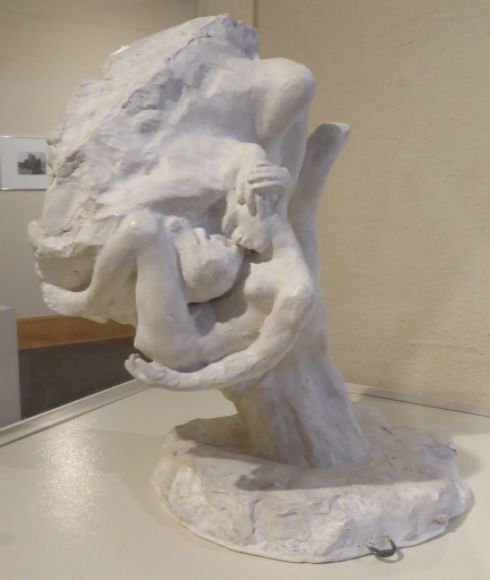

Shown above are some of Rodin’s fragments.

Shown above are some of Rodin’s fragments.