The War to End All Wars?

Lest We Forget, it is Veteran’s Day — November 11, 2019

Lest We Forget, it is Veteran’s Day — November 11, 2019

On September 1, 1939, the armed forces of Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany invaded Poland with overwhelming force, lightning speed, and unprecedented ferocity. World War II had begun and the term "Blitzkrieg" would enter our vocabulary along with all the negative connotations it implied. More than two decades earlier by August 1914, the idea of total war between great industrialized nations had already arrived with a vengeance. After one thousand, five hundred and fifty-one days of intense fighting and nine million dead and many more wounded or missing, on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of the year 1918, the guns of war would finally fall silent. World War I had come to an end but not before an entire generation of European men had been lost. It was a brutal and destructive war -- one whose global reverberations are felt even to this day.

Given that it is a complex topic, this diary is not a comprehensive history of World War I. It only explores some of the themes from that senseless war and the response of a few soldier-poets directly affected by it. I first posted a version of this diary on November 11, 2012.

The haunting music accompanying Owen’s classic poem in the above video is composer Samuel Barber's "Adagio for Strings." It is one of the best videos I have ever seen.

The haunting music accompanying Owen’s classic poem in the above video is composer Samuel Barber's "Adagio for Strings." It is one of the best videos I have ever seen.

Wilfred Owen eventually came to be revered as one of the great British poets of World War I. In what is probably his most famous poem, he describes the futility of war and appalling conditions he experienced while surviving chemical gas attacks in trenches as a soldier during that most brutal of conflicts. The poem's title was inspired by a line in one of the Odes of the ancient Roman poet, Horace. The Latin phrase Dulce et decorum est pro Patria Mori means "how sweet and fitting it is to die for one's country." Even a cursory reading of the poem makes it obvious that an indignant Owen strongly disagrees with Horace and vigorously challenges that misguided notion of personal and imperial glory that Horace later came to be associated with.

Owen had defiantly mocked the idea that there was honor in dying for one's own country. Ironically, that is exactly what he ended up doing. After a stay at Craiglockhart War Hospital in late 1917, Owen returned to France to rejoin his military unit. One week before the war would end, he was caught in a German machine gun attack and killed in action on November 4, 1918. On the day the war ended on November 11, 1918, the sound of church bells in Shrewsbury, England signaled the coming of the long-awaited peace. At the home of his parents, the doorbell rang and a telegram informed them that Owen had been killed the week before.

Only 25 years old at the time of his death, Owen had planned to publish a collection of war poems in 1919. In the book's preface, he had written

Death doesn't always have the last word. What eludes the living - be it fame, fortune, or some other form of notoriety - is often only apparent after they have departed this good earth. So it was for Wilfred Owen.

Death doesn't always have the last word. What eludes the living - be it fame, fortune, or some other form of notoriety - is often only apparent after they have departed this good earth. So it was for Wilfred Owen.

This book is not about heroes. English Poetry is not yet fit to speak of them. Nor is it about deeds, or lands, nor anything about glory, honour, might, majesty, dominion, or power, except war. Above all I am not concerned with Poetry.

My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity. Yet these elegies are to this generation in no sense consolatory. They may be to the next. All a poet can do today is warn. That is why true Poets must be truthful.

"Adagio for Strings" was first performed in 1938 by the NBC Symphony Orchestra and conducted by Arturo Toscanini in front of an invited radio studio audience in New York City. One of President John F. Kennedy's favorite pieces of music, it was played on television upon the announcement of his death on November 22, 1963. You can read a draft of the poem that Owen wrote while recuperating from shell shock at Craiglockhart War Hospital, near Edinburgh, Scotland in 1917.

What Were They Fighting For?

Edmund Blinden would later teach poetry at Oxford University.

Edmund Blinden would later teach poetry at Oxford University.

By the end of the day both sides had seen, in a sad scrawl of broken earth and murdered men, the answer to the question. No road. No thoroughfare. Neither race had won, nor could win, the War. The War had won, and would go on winning.

Poet Edmund Blunden, quoted in David Burg's Almanac of World War I, p. xii. A prolific poet and noted academic, he was nominated multiple times for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

It was said that World War I was fought from 1914-1918 to end all wars. Rather than prevent future conflicts, it resulted, instead, in unprecedented levels of casualties and set the stage for even more horrific wars to come. The killings would continue well into the twentieth century and beyond.

The war shook many people's confidence in humanity to conduct itself with purpose and dignity. After almost three years of senseless killings, mass slaughter, and stalemate on the battlefield, men asked of themselves: what exactly are we fighting for? To advance the great game of geopolitics envisioned by aging statesmen? To bolster the careers of obstinate military leaders? To satisfy the appetites of sovereigns blinded by national pride and enveloped in delusions of grandeur? To engage in imperialist practices with the intent to manipulate, exploit, and plunder weaker nations? Was there a method to this madness? Was there no end in sight and no way out? As the violence showed no signs of abating, the answers would elude statesmen, soldiers, and civilians.

By early 1917, many of the combatants on both the western and eastern fronts began to question their superiors and the very motives for prolonging the fighting. Most yearned for the predictable comfort of their homes and the pedestrian nature of normal, everyday existence so they could carry on peacefully with their lives.

During this period of chaos and instability, World War I would also result in some of the best literature ever written about any conflict in human history. These painfully personal recollections would strip bare nineteenth-century notions of romanticism and expose the grim realities of total war.

“In Flanders Field” and Criticism

"In Flanders Field" is one of the more poignant poems of World War I. It was written by a Canadian physician and poet Lt. Colonel John McCrae on May 2nd, 1915. In it, McCrae was evoking the memory of his dead comrades and in particular, remembering a fellow soldier from Canada, Lt. Alexis Helmer, who died in the 2nd Battle of Ypres in Belgium.

The war to end all wars, it was not!

The war to end all wars, it was not!

Not everyone sees the poem as symbolic of the ultimate sacrifice made by millions of men on the Allied side, even as they fought bravely without full comprehension of the very reasons that compelled them to take up arms in the first place. University of Pennsylvania literary and cultural historian Paul Fussell wrote critically of the poem for he saw its ending as an argument for perpetuating the cycle of war.

As with his earlier poems, "In Flanders Fields" continued McCrae's preoccupation with death and how it stood as the transition between the struggle of life and the peace that followed. It was written from the point of view of the dead. It spoke of their sacrifice and served as their command to the living to press on. Historian Paul Fussell criticized the poem in his work The Great War and Modern Memory. He noted the distinction between the pastoral tone of the first nine lines and the "recruiting-poster rhetoric" of the third stanza. Describing it as "vicious" and "stupid," Fussell called the final lines a "propaganda argument against a negotiated peace." As with many of the most popular works of the First World War, it was written early in the conflict, before the romanticism of war turned to bitterness and disillusionment for soldiers and civilians alike.

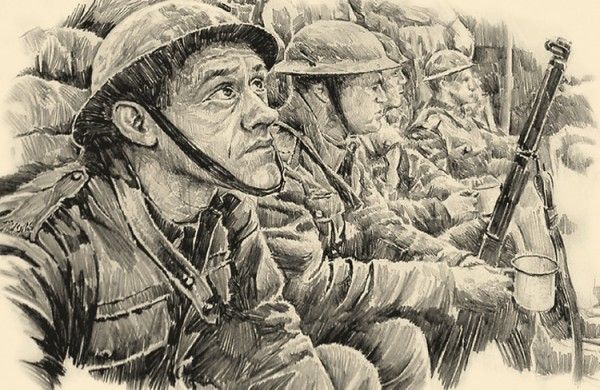

In another superb book, Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War - one based on his recollections as a soldier in that war - Professor Fussell detailed the "absurdities, stupidities, and dehumanizing banalities of military behavior" and forcefully asserted that the purpose of any war from the perspective of the average soldier is the war itself. In that book (which I highly recommend), Professor Fussell urges us not to believe and accept the sanitized and romanticized versions of war brought to us by Hollywood movies. See the more detailed discussion about the reasons countries go to war in this 2007 diary I wrote - "Shared National Sacrifice" and 'The War' Tonight on PBS. Sketch credit: St. Paul's.

Jingoism and the War’s Causes

|

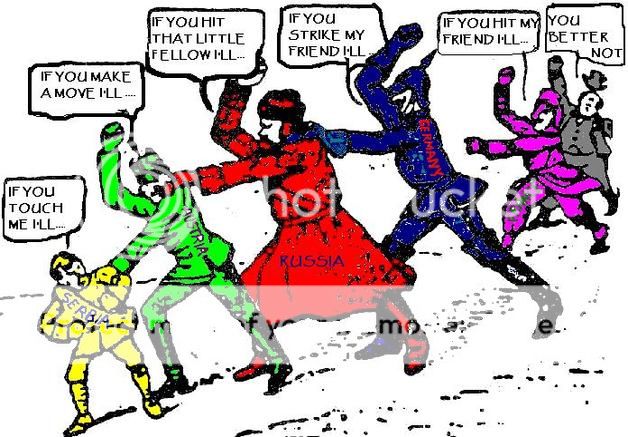

The above sketch visually tries to explain the complex set of treaties and alliances which drew the Great Powers in and expanded the war. The war’s causes are still being debated today by historians.

The above sketch visually tries to explain the complex set of treaties and alliances which drew the Great Powers in and expanded the war. The war’s causes are still being debated today by historians.

The World War of 1914-18 - The Great War, as contemporaries called it -- was the first man-made catastrophe of the 20th century. Historians can easily identify the literal "smoking gun" that set the War in motion: a revolver used by a Serbian nationalist to assassinate Archduke Franz Ferdinand (heir apparent to the Austro-Hungarian throne) in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914.

But scholars are still debating the underlying causes. Was it the desire for greater empire, wealth and territory? A massive arms race? The series of treaties which ensured that once one power went to war, all of Europe would quickly follow? Was it social turmoil and changing artistic sensibilities brought about by the Industrial Revolution? Or was it simply a miscalculation by rulers and generals in power? ...

True to the military alliances, Europe's powers quickly drew up sides after the assassination. The allies - chiefly Russia, France, and Britain - were pitted against the Central Powers - primarily Germany, Austria-Hungary and Turkey. Eventually, the War spread beyond Europe as the warring continent turned to its colonies and friends for help. This included the United States, which joined the War in 1917 when President Woodrow Wilson called on Americans to "make the world safe for democracy."

Most of the leaders in 1914 had no real idea of the war machine they were putting into motion. Many believed the War would be over by Christmas 1914.

"Introduction to the Great War" - The Great War and the Shaping of the Twentieth Century (PBS). This joint PBS/BBC project was produced in association with The Imperial War Museum in 1996. You can watch the entire eight-part series on YouTube. You can also read about one of the rare instances of civility in the war in this diary that I wrote a few years ago - The Night the Guns of War Fell Silent and the Carnage Stopped. Sketch credit: Wikispaces.

|

Kaiser Wilhelm II was eager to expand Germany’s influence around the world, even by military means.

Kaiser Wilhelm II was eager to expand Germany’s influence around the world, even by military means.

Why did World War I break out in 1914? While the immediate cause may be apparent to many, there is considerable discussion amongst historians even to this day as to what the real underlying causes were for this most brutal of conflicts. There was a flurry of diplomatic activity in many European capitals to prevent the outbreak of war. With limited means of communications and no world body like the League of Nations or the United Nations to set the pause button, war seemed inevitable.

When it all started in August 1914 - and after Germany had sided with Austria-Hungary due to treaty obligations - Kaiser Wilhelm II was so confident about a quick victory that he boasted of having "Paris for lunch, St. Petersburg for dinner." Contrary to many reports in the mainstream press of initial irrational exuberance among some people at the time - and unlike their leaders' selfish political aims - most people did not celebrate the news with joy. Rather, there was a stoic resolve to do their national duty. (Click this link here for more propaganda posters from World War I)

Regardless of who bore the brunt of the responsibility of plunging the world into global conflict, when war breaks out nationalistic impulses frequently take over - something true even to this day when it is repeatedly asserted that democracies are slow in mobilizing for the march towards war.

Journalist John Reed had graduated from Harvard College in 1910 and counted among his classmates two other prominent Americans, journalist/political commentator Walter Lippmann, and author/poet T.S. Eliot. The below Chicago Tribune editorial cartoon shows the allied powers pointing fingers towards Germany and Austria. However, Reed saw World War I largely as an imperialist war based on irrational national pride and desire for colonialist expansion. He was firmly opposed to American participation in the war.

Blaming the other guy!

Blaming the other guy!

Was the war a clear cut case of the forces of good fighting the dark, evil forces of greed? In a scathing column published in The New Masses, Reed recounted the events that had taken place in the decades preceding the war and tied them to imperialist ambitions on part of most of the combatants. The competition for international trade and markets had spurred an arms build-up which, in his opinion, would inevitably and unsurprisingly result in conflict. He reserved his harshest comments for Kaiser Wilhelm and his jingoistic attitudes. At the time, Germany as a country and nation was considered to be the epitome of high culture and civilization. It possessed a growing economy second only in size to the United States, great social welfare programs, a largely-educated workforce, and significant achievements in art, philosophy, literature, architecture, music, and the sciences.

How, then, Reed wondered, can one interpret the Kaiser's belligerence and fairly construe it as civilized behavior?

"The Deserter" was an anti-war editorial cartoon by Canadian-American cartoonist Boardman Robinson and depicts a pacifistic Jesus being shot by European soldiers from five countries on both sides of the war.

"The Deserter" was an anti-war editorial cartoon by Canadian-American cartoonist Boardman Robinson and depicts a pacifistic Jesus being shot by European soldiers from five countries on both sides of the war.

| No recent words have seemed to me so ludicrously condescending as the Kaiser's speech to his people when he said that in this supreme crisis he freely forgave all those who had ever opposed him. I am ashamed that in this day in a civilized country any one can speak such archaic nonsense as that speech contained. But worse than the "personal government" of the Kaiser, worse even than the brutalizing ideals he boasts of standing for, is the raw hypocrisy of his armed foes, who shout for a peace which their greed has rendered impossible.

More nauseating than the crack-brained bombast of the Kaiser is the editorial chorus in America which pretends to believe - would have us believe - that the White and Spotless Knight of Modern Democracy is marching against the Unspeakably Vile Monster of Medieval Militarism. What has democracy to do in alliance with Nicholas, the Tsar? It is Liberalism which is marching from the Petersburg of Father Gapon, from the Odessa of Progroms? Are our editors naive enough to believe this?

No. There is a falling out among commercial rivals. One side has observed the polite forms of diplomacy and has talked of "peace" - relying the while on the eminently pacific navy of Great Britain and the army of France and on the millions of semi-serfs whom they have bribed the Tsar of All the Russias (and The Hague) to scourge forward against the Germans. On the other side there has been rudeness - and the hideous Gospel of Blood and Iron.

We, who are Socialists, must hope - we may even expect - that out of this horror of bloodshed and dire destruction will come far-reaching social changes - and a long step forward towards our goal of peace among men. But we must not be duped by this editorial buncombe about Liberalism going forth to Holy War against Tyranny. This is not our war.

John Reed, "The Traders War," The Masses, Marxists.Org, September 1914. Reed was portrayed by actor Warren Beatty in the 1981 movie Reds. Contributors to this graphically innovative Socialist journal also included other notable progressives of the day like Dorothy Day, Carl Sandburg, Upton Sinclair, and Louise Bryant. Robinson, Reed, and other writers from The Masses were tried for treason under the Espionage Act of 1917 but acquitted by a jury. Cartoon credits: Wikipedia and Today in Social Sciences. The first poster is an Italian portrayal of Kaiser Wilhelm II from 1915 and depict his imperialist designs. Poster credit: Spartacus Educational (U.K.).

|

War and Societal Changes

Prolonged military conflicts impact societies in unpredictable ways. Many changes were set into motion by World War I, particularly the effect it had on redefining relationships between social classes in Britain. The dynamic between the upper classes (from where most officers came) and the working classes (who contributed enlisted personnel) in that most horrendous of conflicts had been altered. One factor that contributed to this change was long periods spent together in warfare - mostly in close proximity in trenches by all classes of soldiers - with only one common goal in mind: survival. It simply meant that the old, hierarchical social order was crumbling, the distance between classes narrowing considerably, and new realities making British society gradually more egalitarian. This change was not without its problems as the attitude of upper classes evolved only slowly, but by the war's end, change was discernible.

In Britain, there was an early "rally around the flag" effect in which many writers squarely laid the blame at Germany's aggressive military policies

This propaganda poster encourages British men to enlist together as part of the Pals Battalion in the British army. In order to foster unity among fighting men, friends, neighbors, members of social/sports groups, and work colleagues were recruited as a group and promised assignments to the same units.

This propaganda poster encourages British men to enlist together as part of the Pals Battalion in the British army. In order to foster unity among fighting men, friends, neighbors, members of social/sports groups, and work colleagues were recruited as a group and promised assignments to the same units.

The early poetry put forward the view that Britain could not have avoided going to war in 1914; that the Germans "were powerful and were so fond of bullying their neighbours that Britain could not have deterred them from beginning a world war." For example, the novelist Thomas Hardy in Men Who March Away claimed that "the braggarts must surely bite the dust". Rudyard Kipling wrote that "The Hun is at the gate" and that the men of Britain had to fight against a regime that acknowledged "no law except the sword".

Most of this early poetry also reflected the unrealistic, over-optimistic and sentimental attitude of the British people to war in 1914. Most nations believed that the war would be short and over by Christmas expecting their armies to win an immediate, decisive victory.

The war was also seen as a Christian crusade that would bring a new nobility to those who took part in it. So many men enlisted in a mood of optimistic exhilaration, assuming the war would be both chivalrous and heroic and would make better men of those who fought.

Lord Kitchener (with mustache) was the British Secretary of State for War from 1914-1916 and his image was widely used on recruitment posters. In the above poster, he is seen inspecting Australian troops in 1915 during the disastrous Gallipoli Campaign.

Lord Kitchener (with mustache) was the British Secretary of State for War from 1914-1916 and his image was widely used on recruitment posters. In the above poster, he is seen inspecting Australian troops in 1915 during the disastrous Gallipoli Campaign.

"War Poetry" - Charles Sturt University (New South Wales, Australia). The Military Service Act in 1916 would end voluntary recruitment and make all men between the ages of 18-51 (with some exceptions) eligible for conscription. Poster credits: Squidoo and McMaster University Libraries (Canada).

An unabashed champion of British imperialism, Rudyard Kipling was, nevertheless, a great Victorian and Edwardian writer. He won the Nobel Peace Prize for Literature in 1907 and was widely read in English-speaking countries. For extolling the virtues of the British Empire and his literary achievements, he was offered a knighthood and post of Poet Laureate but turned down both offers.

Soon after the realities of prolonged trench warfare and stalemate set in on the Eastern front, initial war euphoria dissipated and all combatants dug in for the long haul. Kipling strongly pushed his son Jack to enlist and fight for his beliefs. Twice rejected by the British army due to crippling shortsightedness, Jack was only able to join the fighting in France after his famous father pulled some political strings. In 1915, Jack was reported missing in the Battle of Loos. Years would go by before Kipling would learn anything definitive about his son's fate.

Searching desperately for his son, Kipling penned the below poem - a cry of anguish from a concerned parent

My Boy Jack

By Rudyard Kipling

"Have you news of my boy Jack?"

Not this tide.

"When d’you think that he’ll come back?"

Not with this wind blowing, and this tide.

"Has any one else had word of him?"

Not this tide.

For what is sunk will hardly swim,

Not with this wind blowing, and this tide.

"Oh, dear, what comfort can I find?"

None this tide,

Nor any tide,

Except he did not shame his kind —

Not even with that wind blowing, and that tide.

Then hold your head up all the more,

This tide,

And every tide;

Because he was the son you bore,

And gave to that wind blowing and that tide!

Read more about this heartbreaking story in the PBS drama "My Boy Jack" - PBS. You can also watch the entire movie on YouTube. (Spanish subtitles) While acknowledging his contributions to the English language, author George Orwell referred to Kipling as the "prophet of British imperialism."

Author Erich Maria Remarque had a remarkable capacity to write about the horrors of war.

Author Erich Maria Remarque had a remarkable capacity to write about the horrors of war.

If things went according to the death notices, man would be absolutely perfect. There you find only first-class fathers, immaculate husbands, model children, unselfish, self-sacrificing mothers, grandparents mourned by all, businessmen in contrast with whom Francis of Assisi would seem an infinite egoist, generals dripping with kindness, humane prosecuting attorneys, almost holy munitions makers - in short, the earth seems to have been populated by a horde of wingless angels without one's having been aware of it.

"Prose & Poetry - Erich Maria Remarque" - The Black Obelisk. This novel by Remarque depicts life in post-World War I Germany, a defeated country beset by economic turbulence and rising nationalism. Having fought as a German soldier in WW I, he is perhaps best known for another novel describing the alienation experienced by veterans upon returning home to Germany, All Quiet on the Western Front. Photograph credit: Audiolibros Gratis.

How did World War I affect German soldiers? The horrors of war were experienced in

all countries during World War I.

Otto Dix was a German painter and relentless critic not only of the war, but also Weimar society in post-War Germany.

Below is a painting by Dix along with a poem written in 1915 by an unknown German soldier. See more of Dix's paintings and sketches, along with this terrific article on Dix by Art History and Philosophy Professor at SUNY Stony Brook, Donald Kuspit.

Self-Portrait, 1914 by Otto Dix.

Self-Portrait, 1914 by Otto Dix.

Argonne Forest At Midnight

A Sapper's Song from the World War

Argonne Forest, at midnight,

A sapper stands on guard.

A star shines high up in the sky,

bringing greetings from a distant homeland.

And with a spade in his hand,

He waits forward in the sap-trench.

He thinks with longing on his love,

Wondering if he will ever see her again.

The artillery roars like thunder,

While we wait in front of the infantry,

With shells crashing all around.

The Frenchies want to take our position.

Should the enemy threaten us even more,

We Germans fear him no more.

And should he be so strong,

He will not take our position.

The storm breaks! The mortar crashes!

The sapper begins his advance.

Forward to the enemy trenches,

There he pulls the pin on a grenade.

The infantry stand in wait,

Until the hand grenade explodes.

Then forward with the assault against the enemy,

And with a shout, break into their position.

Argonne Forest, Argonne Forest,

Soon thou willt be a quiet cemetary.

In thy cool earth rests

much gallant soldiers' blood.

War Without Purpose - Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, and Robert Graves

As novelist Erich Maria Remarque pointed out above, many people put up a façade in times of war and behave in conformist fashion simply because society demands that they conduct themselves in a certain way. How one outwardly appears to others may not necessarily represent reality or, even, one’s perception of oneself. Appearances, as it is often said, can be deceiving.

So was the case with Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, and Robert Graves - three of the most famous British poets and soldiers of World War I. By the second year of the war, along with millions of fighting men, they had realized that this horrendous conflict was not going to be over any time soon

By 1915, the war was being fought with the ruthlessness that seemed new and terrible. Both sides began to realise how horrific and inexhaustible were the sheer powers of destruction that were being deployed. Also, they began to doubt whether there was any hope of either side winning a swift victory. There was a deadlock on the Western Front. Long lines of trenches had been construed from the North Sea to the Alps. Allied Generals launched massive frontal attacks that proved to be futile and an obscene waste of human life.

As more and more British soldiers began to experience the horrors and discomforts of trench warfare and as they also began to doubt the wisdom of the tactics that led to spectacularly unsuccessful attacks of late 1915, such as Loos. Their poetry began to ask disconcerting questions or to express doubts.

Soldiers, especially young soldiers, began to lose faith in the British class system that promoted officers according to what school they went to, rather than on their ability. Soldiers began to feel a race apart from the civilians at home, many of whom were making profits out of the War. They seemed also to enjoy second hand accounts and experiences of the War by following the battles in the press [e.g. Paul's home leave in All Quiet on the Western Front]. They also lost faith in a God who permitted these things to occur.

Sketch credit: Lewis Boadle.

Sassoon was 28 years old when World War I broke out. Coming from a very affluent family, his Spanish-Jewish father had left the family when Sassoon was only 5 years old and died soon after. Cambridge-educated, Sassoon was already a published poet and given his love of pastoral life in England, had been favorably compared to Thomas Hardy.

Leading a life of leisure in Kent - one which involved horse riding, cricket, golf, and fox hunting - he was in uniform the day after the war started. His initial enthusiasm soon gave way to feelings of cynicism and outrage. Critical of how the war was being conducted, he was, nonetheless, motivated by a strong sense of duty and conducted himself very bravely. Beloved by his men who called him “Mad Jack” for his daring forays into enemy territory, one of them wrote later on about him, "It was only once in a blue moon that we had an officer like Mr. Sassoon."

The above video is from the 1990s ABC television series, "The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles" - a fictionalized account in which Jones meets Lt. Siegfried Sassoon and Lt. Robert Graves in wartime Belgium.

You will get a really good sense of why so many men who went to war were so disillusioned by it. At the 2:35 mark of the video, Sassoon laments the continued loss of good men. He wistfully recalls that he had enlisted in the war to preserve peace and freedom. Even while doing his patriotic duty, he complains vociferously about munitions makers in England and the enormous profits reaped in by industrialists. Graves is upset by such talk and leaves the other two. At this point, Jones asks Sassoon as to why he keeps participating in this war despite his misgivings and cynicism. Sassoon replies in a matter-of-fact manner, “Because it’s my duty!”

Does it Matter?

by Siegfried Sassoon

Once the war is over, society expects soldiers to return home and resume their normal lives. Sassoon wonders, is that even possible?

Once the war is over, society expects soldiers to return home and resume their normal lives. Sassoon wonders, is that even possible?

Does it matter? - losing your legs?

For people will always be kind,

And you need not show that you mind

When others come in after hunting

To gobble their muffins and eggs.

Does it matter? - losing your sight?

There’s such splendid work for the blind;

And people will always be kind,

As you sit on the terrace remembering

And turning your face to the light.

Do they matter? - those dreams in the pit?

You can drink and forget and be glad,

And people won't say that you’re mad;

For they know that you've fought for your country,

And no one will worry a bit.

Siegfried Sassoon's Long Journey: Selections from the Sherston Memoirs, edited by Paul Fussell, pp. x-xii. Friends with both Wilfred Owen and Sassoon, Robert Graves wrote one of the more memorable accounts of World War I, Goodbye to All That. The book deals with how the war swept away the old order in Europe and ushered in significant changes that touched every aspect of life.

Disgusted by the callousness of the British military high command, Sassoon - a decorated army hero - did something unthinkable in 1917.

Sassoon had meanwhile developed increasingly angry feelings concerning the conduct of the war. This led him to publish, in The Times, a letter announcing his view that the war was being deliberately and unnecessarily prolonged by the authorities. Sassoon narrowly avoided punishment by courts-martial via the swift assistance of Robert Graves, who convinced the military review board (with Sassoon's reluctant consent) that Sassoon was suffering from shell shock. Consequently, Sassoon was sent to Craiglockhart military hospital to recover. It was while at Craiglockhart that Sassoon met and struck up a friendship with Wilfred Owen. Sassoon subsequently edited and arranged the publication of Owen's work after the war.

Lieutenant Siegfried Sassoon was a decorated war veteran just “doing his duty.”

Lieutenant Siegfried Sassoon was a decorated war veteran just “doing his duty.”

I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority because I believe that the war is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it. I am a soldier, convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers. I believe that the war upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation has now become a war of aggression and conquest. I believe that the purposes for which I and my fellow soldiers entered upon this war should have been so clearly stated as to have made it impossible to change them and that had this been done the objects which actuated us would now be attainable by negotiation.

I have seen and endured the sufferings of the troops and I can no longer be a party to prolonging these sufferings for ends which I believe to be evil and unjust. I am not protesting against the conduct of the war, but against the political errors and insincerities for which the fighting men are being sacrificed.

On behalf of those who are suffering now, I make this protest against the deception which is being practised upon them; also I believe it may help to destroy the callous complacency with which the majority of those at home regard the continuance of agonies which they do not share and which they have not enough imagination to realise.

|

The cavalier attitudes of the High Command were captured perfectly by Sassoon in his poem, "Great Men." The lie and the reality - older men sending younger men into battle to die while invoking honor, duty, and country. It reminds one of the lyrics from Pink Floyd's classic song, "Us and Them" (YouTube video)

Us and Them

And after all, we're only ordinary men

Me, and you

God only knows it's not what we would choose to do

Forward he cried from the rear

and the front rank died

And the General sat, as the lines on the map

moved from side to side

Great Men

by Siegfried Sasson

Grand strategies, geopolitical objectives, and tactical battle plans are for politicians and generals. In a Democratic society, soldiers don't make the decision to engage in war; political leaders, some with perverted personal agendas, do.

Grand strategies, geopolitical objectives, and tactical battle plans are for politicians and generals. In a Democratic society, soldiers don't make the decision to engage in war; political leaders, some with perverted personal agendas, do.

The great ones of the earth

Approve, with smiles and bland salutes, the rage

And monstrous tyranny they have brought to birth.

The great ones of the earth

Are much concerned about the wars they wage,

And quite aware of what those wars are worth.

You Marshals, gilt and red,

You Ministers and Princes, and Great Men,

Why can’t you keep your mouthings for the dead?

Go round the simple Cemeteries; and then

Talk of our noble sacrifice and losses

To the wooden crosses.

It is important to note that the field of psychiatry was not as advanced in the early twentieth century as it is today. There were hundreds of thousands of men who were traumatized by "shell shock" - or Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome (PTSD) as it is called almost a hundred years later. Learning to survive amongst wretched conditions in trenches while enduring the daily explosion of hundreds of exploding shells around them would invariably affect the bravest of soldiers.

After breaking down on the front, both Owen and Sassoon ended up in 1917 at Craiglockhart War Hospital near Edinburgh, Scotland under the care of Dr. W. H. R. Rivers.

Mental Cases

by Wilfred Owen

Who are these? Why sit they here in twilight?

Wherefore rock they, purgatorial shadows,

Drooping tongues from jaws that slob their relish,

Baring teeth that leer like skulls’ teeth wicked?

Stroke on stroke of pain, — but what slow panic,

Gouged these chasms round their fretted sockets?

Ever from their hair and through their hands’ palms

Misery swelters. Surely we have perished

Sleeping, and walk hell; but who these hellish?

These are men whose minds the Dead have ravished.

Memory fingers in their hair of murders,

Multitudinous murders they once witnessed.

Wading sloughs of flesh these helpless wander,

Treading blood from lungs that had loved laughter.

Always they must see these things and hear them,

Batter of guns and shatter of flying muscles,

Carnage incomparable, and human squander

Rucked too thick for these men’s extrication.

Therefore still their eyeballs shrink tormented

Back into their brains, because on their sense

Sunlight seems a blood-smear; night comes blood-black;

Dawn breaks open like a wound that bleeds afresh.

Thus their heads wear this hilarious, hideous,

Awful falseness of set-smiling corpses.

Thus their hands are plucking at each other;

Picking at the rope-knouts of their scourging;

Snatching after us who smote them, brother,

Pawing us who dealt them war and madness.

You can watch this excellent movie "Regeneration" in full on YouTube. Based on the prize-winning anti-war novel by Pat Barker, it shows a very sensitive Dr. Rivers befriending his two patients, Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, at Craiglockhart Hospital. Using innovative psychiatric techniques, he takes exceptionally good care of both soldiers. Read more about Dr. Rivers here and also about this movie here and here. Painting credit: KharBevNor.

How did the great poets of World War I contribute to our understanding of war? So much so that their poems are being widely read by modern armies

READ MORE ABOUT ALL THE OTHER WORLD WAR I POETS.

The Great War still compels the imagination. It continues to shape how we think about war, and its poets continue to suggest how we might feel about war. American troops training for Afghanistan in 2001 studied not just maps and military procedures but the poems of Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon and Rupert Brooke. One young sergeant from Portland, Oregon picked out Owen's 'Dulce et Decorum Est': 'Just by what he said you actually can feel it, or you can get a mental picture of the death or the awful sights.' If a single poem now defines the Great War experience for the English-speaking world - and even modern war in general - it is probably that poem of Owen's about the victim of a gas attack.

A Few Concluding Thoughts

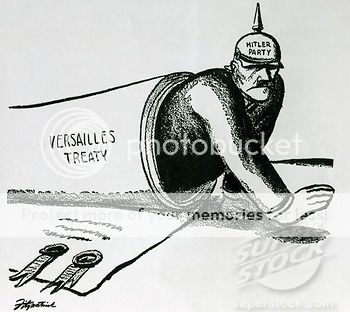

This editorial cartoon shows that the rise of extreme nationalism and Fascism in post-War Germany was a direct result of the harsh terms imposed upon it in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles by the victorious Allies.

This editorial cartoon shows that the rise of extreme nationalism and Fascism in post-War Germany was a direct result of the harsh terms imposed upon it in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles by the victorious Allies.

World War I was unprecedented in its brutality. The first mass genocide took place. Tens of millions were killed, wounded, or were missing in action. Civilians were deliberately targeted. Empires withered away. The Ottoman Empire was a shadow of its own self. In Russia, the Romanov Dynasty collapsed after ruling a vast empire for over three hundred years. Germany entered a phase of limited democracy, albeit a shaky one beset by strife and instability. The Austro-Hungarian Empire gave way to a new political order in Eastern Europe. Britain and France would have their grips loosened upon their colonies. Alone among combatants, the United States would eventually grow stronger and, willingly or not, assume world leadership.

Out of the ashes of war would emerge a world reborn but not until decades later.

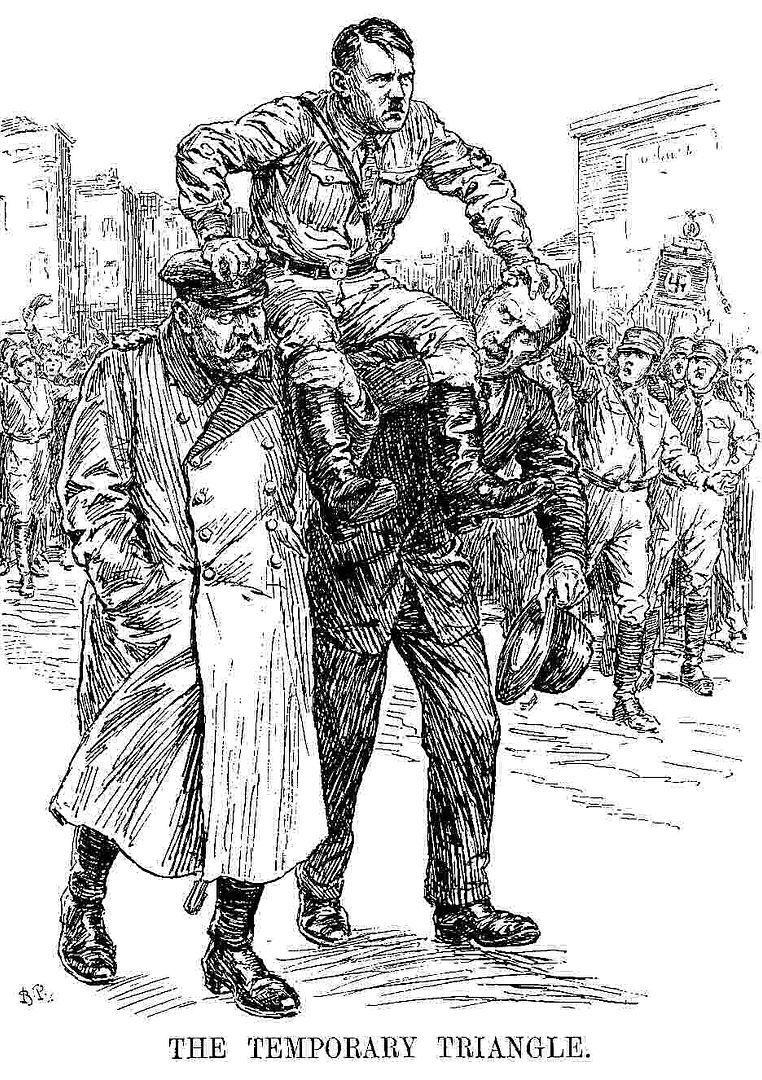

The above1933 cartoon from Punch magazine shows Adolf Hitler is carried to power on the shoulders of President Paul von Hindenburg (left) and Chancellor Franz von Papen (right).

The above1933 cartoon from Punch magazine shows Adolf Hitler is carried to power on the shoulders of President Paul von Hindenburg (left) and Chancellor Franz von Papen (right).

Many historians still wonder what the real reasons were for the war. Was it pride? Honor? Imperialism? An antiquated belief that war was noble? To be sure, autocracy was reduced although not completely eliminated. One set of problems was replaced by another with the rise of Fascism, Imperialism, and Bolshevism along with the failures of Capitalism.

A failed artist and young corporal in the German army by the name of Adolf Hitler would vow to avenge Germany's humiliation at the hands of the Allied forces in World War I. In the years to come, the drums of war would beat even louder.

Casualty figures from World War I.

Casualty figures from World War I.

Lt. Col. John McRae (center) is pictured with Rupert Brooke (left) and Wilfred Owen.

Lt. Col. John McRae (center) is pictured with Rupert Brooke (left) and Wilfred Owen.

While serving in France, John McRae died of pneumonia in January 1918. "In Flanders Field" would become hugely popular in English-speaking countries. The poppy referred to in his poem grew in abundance in Flanders and nearby battlefields containing the graves of thousands of dead soldiers. It would be adopted as the "Flower of Remembrance" on the Allied side of the war.

You can read more about the adoption of the poppy flower as symbolic of remembering the war dead here and here.

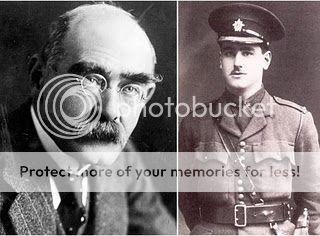

Rudyard Kipling (left) and his son, Jack.

Rudyard Kipling (left) and his son, Jack.

The disappearance of Rudyard Kipling's son, Jack, was a tremendous blow to his parents. He was believed by the army to be wounded and missing in action. Clinging to the hope that at least he was alive, his parents escalated their search but to no avail. They asked anyone and everyone but had no luck.

Two years later in 1917, one of Jack's friends, Private Bowe - who had been suffering from shell shock - arrived at the Kiplings' house and told them that Jack had been killed in September 1915 after only being in France for three weeks. When he died, it had been raining hard and Jack was unable to see anything. The long search was over for the grieving parents. Jack Kipling was eighteen years old.

Poets Siegfried Sassoon and Robert Graves. Both would outlive Wilfred Owen by decades.

Poets Siegfried Sassoon and Robert Graves. Both would outlive Wilfred Owen by decades.

Returning to the war following a spell at Craiglockhart, Siegfried Sassoon was posted to Palestine before returning to France where he was again wounded, forcing a return home to England. In addition to publishing anti-war rhetoric in The Old Huntsman (1917) and Counter-Attack (1918), Sassoon wrote three volumes of classic fictional autobiography loosely based upon his immediate pre-war and war experiences: Memoirs of a Foxhunting Man (1928, initially published under a pseudonym); Memoirs of an Infantry Officer (1930); and Sherston's Progress (1936).

He followed these with three volumes of actual autobiography: The Old Century (1938); The Weald of Youth (1942); and Siegfried's Journey (1945). Sassoon died in 1967 at the age of eighty. link

Edmund Blunden, a close friend of Sassoon, would survive the war and became a professor of poetry at Oxford University. He died in 1974 at the age of 77. Robert Graves (sketch on right) left England and lived most of his life in Majorca, Spain. He passed away in 1985 when he was 90 years old. If his name sounds familiar, it should. He also authored I, Claudius, a historical novel on the Roman Emperor Claudius and one adapted as a popular series in the 1970s for BBC Television.

A Note About the Diary Poll

Was this war necessary?

Was this war necessary?

For it is always a question, when one speaks of imperialism, of the assertion of an aggressiveness whose real basis does not lie in the aims followed at the moment but an aggressiveness in itself. And actually history shows us people and classes who desire expansion for the sake of expanding, war for the sake of fighting, domination for the sake of dominating. It values conquest not so much because of the advantages it brings, which are often more than doubtful, as because it is conquest, success, activity. Although expansion as self-purpose always needs concrete objects to activate it and support it, its meaning is not included therein. Hence its tendency toward the infinite unto the exhaustion of its forces, and its motto: plus ultra. Thus we define: Imperialism is the object-less disposition of a state to expansion by force without assigned limits.

If some of you interpret this diary as an anti-war statement about a futile and senseless war that should have never been fought, only because it is one. Not all wars are unnecessary, but many are just that.

Prussian General Carl Von Clausewitz famously said once that war was simply the continuation of politics by other means. The outbreak of hostilities also signifies, importantly, a failure of diplomacy and conflict resolution. Deliberately or not, some leaders of European countries had been marching towards and preparing for war for a number of years. They did next to nothing to stop it. Once such preparations gather a momentum of their own, it is virtually impossible to reverse the trend. As British military historian John Keegan pointed out, there was a flurry of diplomatic activity and last-minute attempts in various European capitals in July 1914 to reconcile political differences. By then, it was too late and nothing could prevent the Guns of August from erupting loudly for four long years.

Therein lies the tragedy of World War I.

John Keegan, The First World War, pp. 24-47.