How long have American Indians lived in North America? This is a question which has been debated, primarily by Europeans and their descendants, for more than five centuries. By the end of the nineteenth century and during the few two or three decades of the twentieth century, most people were convinced that the various American Indian nations, like the various European colonies, had lived in North America for only a very short time. The “New World,” in other words, did not have great antiquity with regard to human habitation.

During the nineteenth century, archaeologists—scientists who study the past through material remains, including artifacts and ancient buildings—had done a great deal to dispel the fanciful ideas regarding the great mounds and pyramids of North America. Archaeological findings made it clear that these had been constructed by American Indians and not by Vikings, the Welch, the Toltecs, or advanced civilizations from Atlantis or Outer Space. However, archaeology had uncovered relatively few clues regarding the antiquity of American Indian cultures. In their chapter on North America in The Oxford Handbook of Archaeology, Charles Cobb and Randall McGuire write:

“At the beginning of the twentieth century most archaeologists believed that people had only been in North America for a few hundred years before Columbus.”

During the second quarter of the twentieth century, however, new archaeological data began to be uncovered. At archaeological sites in the Southwest stone tools were found in association with extinct mammals. These finds suggested that people had been living in North America for thousands of years.

In 1932, more answers emerged when stone tools were found in association with the remains of an extinct mammoth in a gravel pit near Clovis, New Mexico. With this find, many people viewed Clovis culture—exemplified by a distinctive spear point—as the oldest American culture and the Clovis people were labeled as the First Americans. Subsequent archaeological finds, as well as DNA, have shown that people were living in North America long before Clovis.

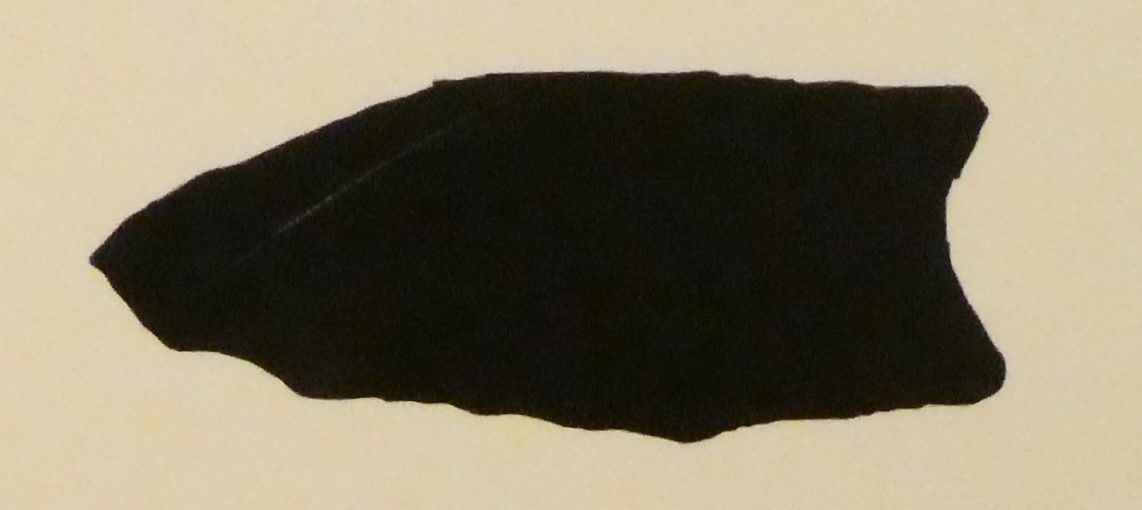

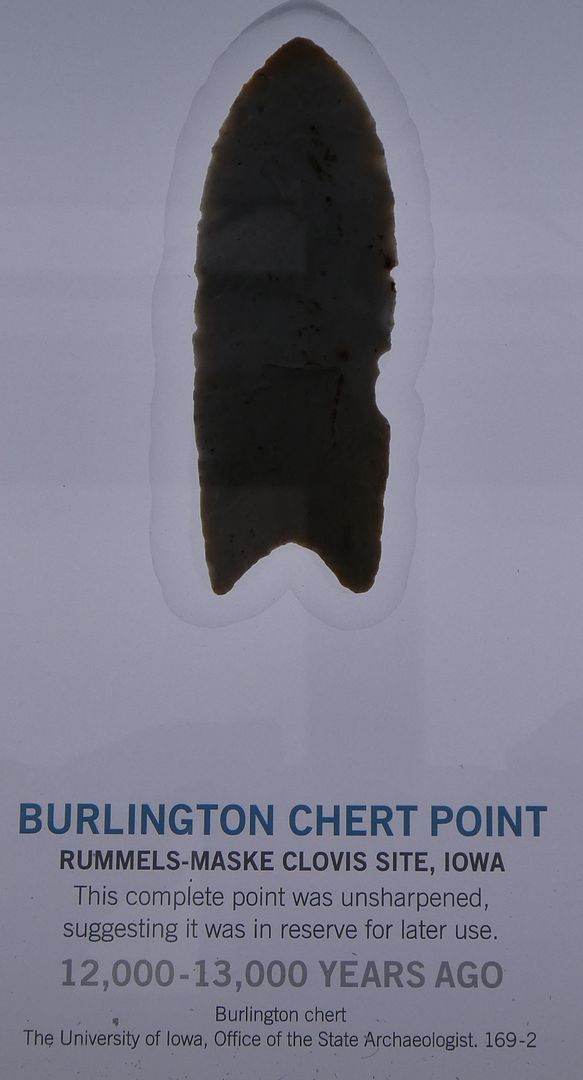

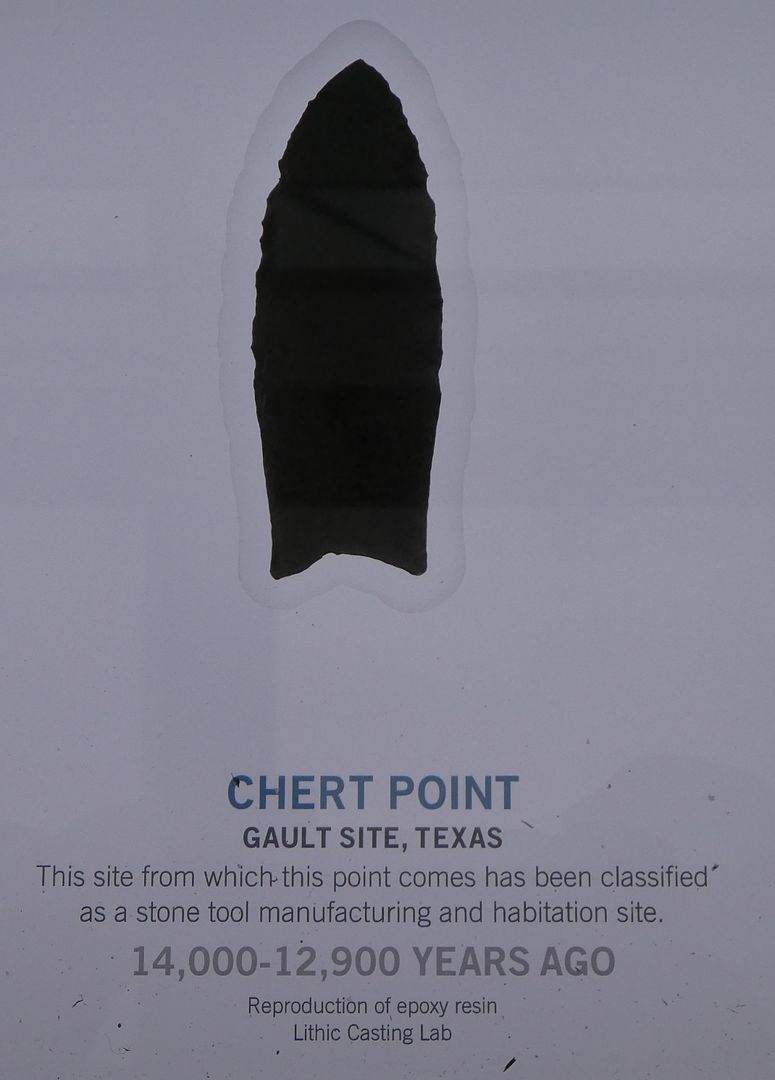

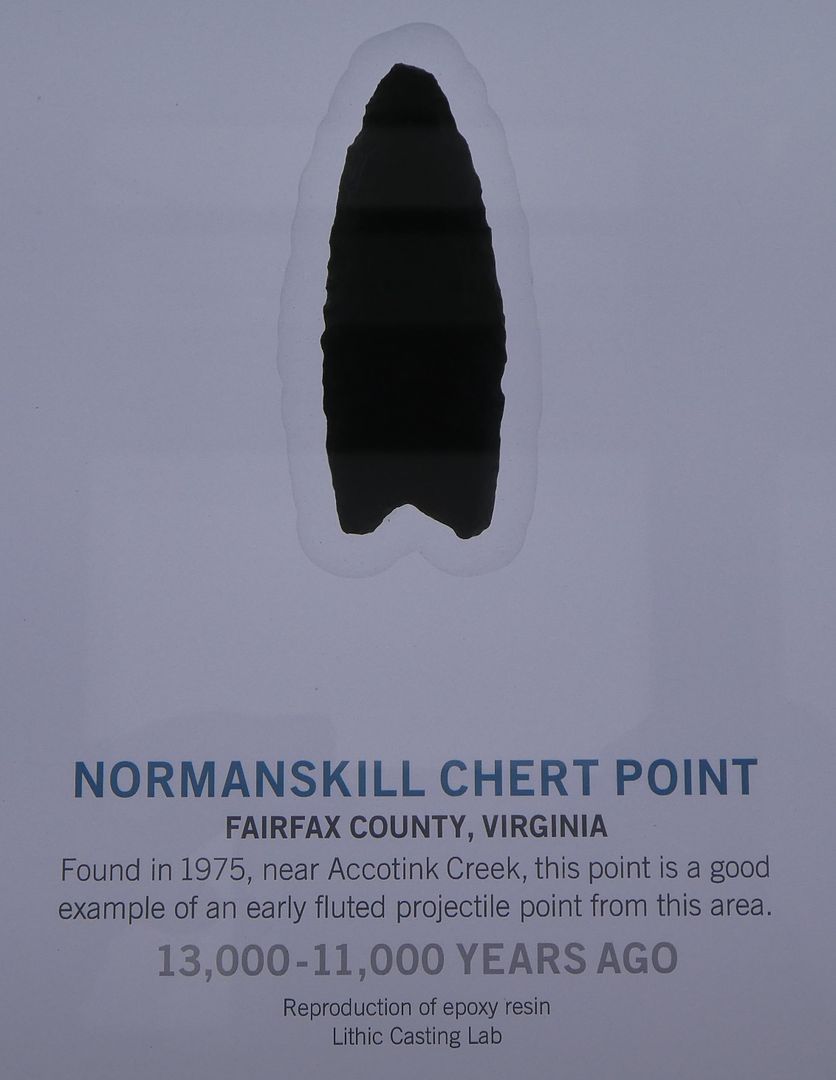

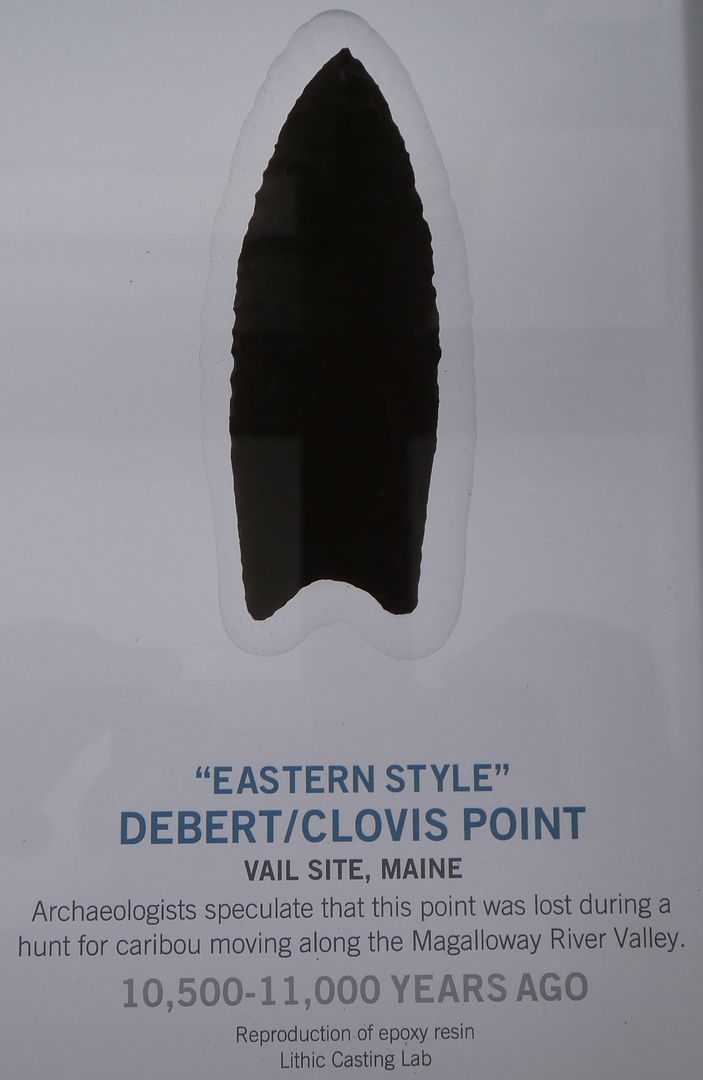

The signature artifact of the Clovis people is an atlatl point. The Clovis point is a finely made stone projectile point with a characteristic flute which helps in attaching the point to an atlatl dart. Clovis points have lateral indentations (or flutes) which allow them to be efficiently tied to a shaft. The shafts were thrown with the aid of a throwing stick or atlatl.

Shown above is an illustration of a Clovis point from the Sacajawea Museum in Kennewick, Washington.

Shown above is an illustration of a Clovis point from the Sacajawea Museum in Kennewick, Washington.

Archaeologist George Frison, in his chapter in Ice Age People of North America: Environments, Origins, and Adaptations, describes the Clovis point this way:

“The Clovis projectile point has a sharp point for initial penetration; blade edges are sharp so as to cut a hole of proper size to allow entry of the hafting element and shaft; the point narrows slightly toward the base to allow a sinew binding that will not impede entry; the flutes provide a basal thinning, which is ideal to fit into the nock of the foreshaft; and the lenticular cross-section provides structural strength. The point is designed to be attached to a wooden foreshaft with sinew and pitch without fear of it loosening during use.”

Archaeologist J.M. Adovasio, in his book The First Americans: In Pursuit of Archaeology’s Greatest Mystery, describes Clovis points this way:

“They were extremely well made, the result of very fine, very controlled chipping, or flaking, and were also ‘fluted,’ meaning that a long vertical flake was chipped off both sides of the point’s based in order to produce grooves. This so-called fluting was unique in the archaeological record anywhere on the planet: only in America.”

While the fluted point is the iconic symbol of Clovis, Clovis sites also have other characteristics. In his chapter in The Oxford Handbook of Archaeology, Steven Mithen writes:

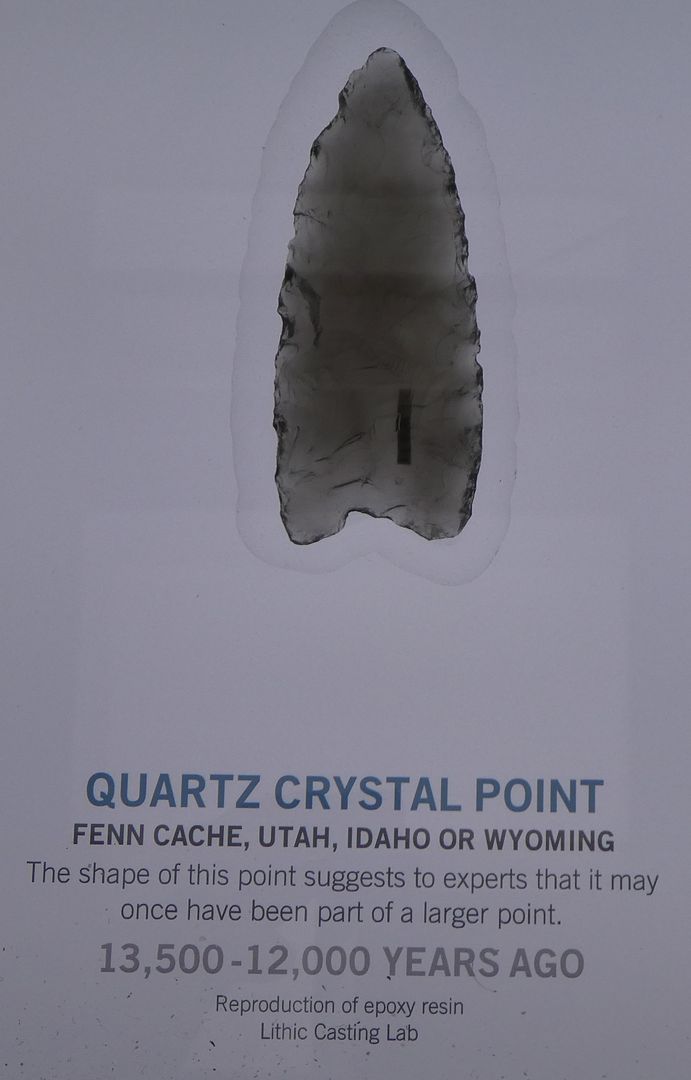

“In addition to its large fluted stone points and occasional mammoth-kill (scavenging?) sites, Clovis is notable for large caches of stone points, some of which were made from particularly colourful or patterns types of stone. Few sites with structures or burials are known, and hence it appears to have been a highly mobile society, with many short-term hunting camps.”

One of the principle weapons used by the Clovis hunters was the atlatl. The atlatl is a wooden shaft with a hook at one end and a handle at the other. The butt of the spear is engaged by the hook. Grasping the handle and steadying the spear shaft with the fingers, the spear can be hurled with great force. Archaeologist L.S. Cressman, in his book The Sandal and the Cave: The Indians of Oregon, notes:

“Thus the atlatl was in principle an extension of the arm and, by the added leverage, gave much greater power to the thrust of the spear.”

With the atlatl the spear can be thrown with greater force and for longer distances than if done by arm and hand alone. It is estimated that the atlatl dart has an impact over 150 times as intense as that of a hand-thrown spear. The atlatl is effective and accurate at ranges up to 150 meters.

Shown above is a replica of the foreshaft of an atlatl dart. This is from a display in the Washington State History Museum in Tacoma.

Shown above is a replica of the foreshaft of an atlatl dart. This is from a display in the Washington State History Museum in Tacoma.

Atlatl darts may have had a foreshaft. At a number of Clovis sites archaeologists have found rods which are beveled on both ends at different angles, and the flat bevels are deeply incised with cross-hatching. The rods may have been attached to another object with a glue of pine pitch as the archaeologists have found the residue of the pine pitch on the rods.

In looking at the questions regarding the origins of Clovis, one of the displays at the Washington State Historical Museum in Tacoma asks:

“Did they trek over the ice fields of the Bering land bridge from Asia or across European plains? Did they travel in small boats, daring ocean waves? Or have they always been here, changing with every turn of the season?”

The map above shows some of the hypotheses regarding the origins of Clovis.

The map above shows some of the hypotheses regarding the origins of Clovis.

Clovis was not the first American culture. While there are still lots of different arguments regarding its origins elsewhere, the fact remains that people were living in North America for thousands of years prior to the development of Clovis technology. In all likelihood, Clovis first evolved in North America. In his chapter in North American Archaeology, archaeologist Kenneth Sassaman writes:

“There is in fact good reason to believe that Clovis is a southeastern U.S. original, and thus necessarily with local antecedents. It follows that Clovis populations in the Southeast had centuries of experience in the region under their collective cultural belt.”

Clovis artifacts, particularly the iconic Clovis points are found at sites throughout North America. This does not mean that there was a unified Clovis culture, but only that Clovis technology diffused across the continent.

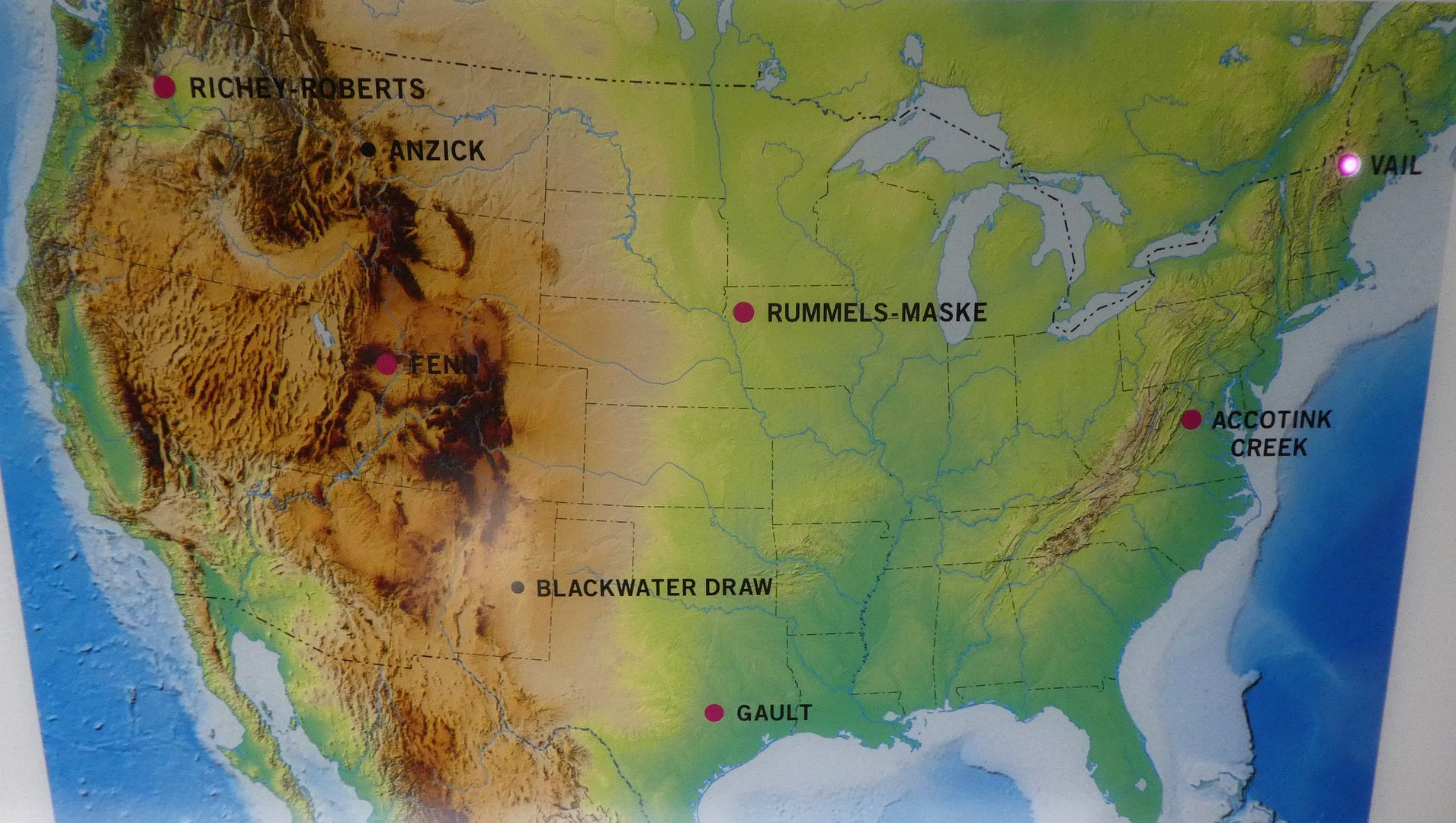

The map above shows the location of some of the Clovis sites in North America.

The map above shows the location of some of the Clovis sites in North America.

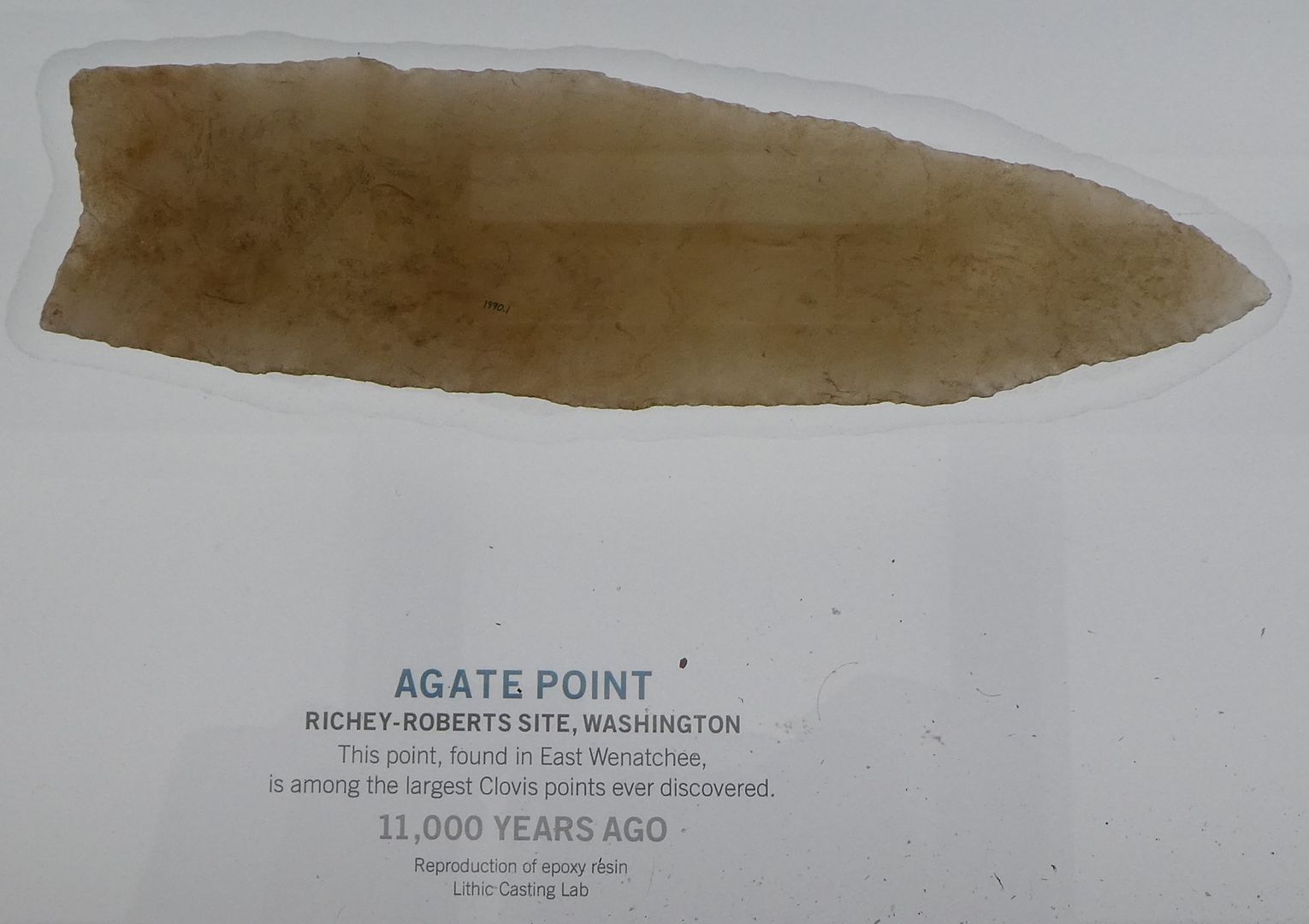

Shown below are the characteristic points for each of the major sites shown on the map.

The Richey-Roberts site near East Wenatchee, Washington, dates to about 11,000 years ago. Clovis people cached a large number of artifacts at this site.

The Richey-Roberts site near East Wenatchee, Washington, dates to about 11,000 years ago. Clovis people cached a large number of artifacts at this site.

In his book Ancient North America: The Archaeology of a Continent, archaeologist Brian Fagan writes:

“The fluted projectile point is the most celebrated, distinctive part of the Clovis toolkit. A cache of some of the finest known specimens came from the East Wenatchee site in Washington State, deposited soon after an eruption of nearby Glacier Peak about 9250 BC.”

The Gualt site in Texas also contains evidence of early American Indian art. In their book Across Atlantic Ice: The Origins of America’s Clovis Culture, archaeologists Dennis Stanford and Bruce Bradley write:

“Small incised stones have been recovered from the Clovis level at the Gault Site in Central Texas. These stones are mostly thin limestone slabs that are natural in the area. The incising is mostly geometric designs, especially hatching and crosshatching, but at least two stones may be etched with animal representations.”

The Vail site was a seasonal hunting site used for killing caribou. The caribou were killed along a sandy patch of ground near the river and then the animals were processed for hide, meat, and marrow. The hunters maintained their camp across the river from the kill site.

The Vail site was a seasonal hunting site used for killing caribou. The caribou were killed along a sandy patch of ground near the river and then the animals were processed for hide, meat, and marrow. The hunters maintained their camp across the river from the kill site.

With regard to their tool kit, hunters at the Vail site were using fluted points with deep concave bases which are similar to those used by the people at the Debert site in Nova Scotia, Canada. While the nearest suitable source for stone for making tools is about 25 kilometers away, the hunters and food processors were using stone tools which came from more distant quarries in Vermont, New York, and Pennsylvania.

The people living at the Vail site were using tents which measured about 4.5 by 6 meters (approximately 15 by 20 feet).

With regard to Clovis sites in the east, David Anderson, in his chapter on Pleistocene settlement in the east in The Oxford Handbook of North American Archaeology, writes:

“Many of these are associated with prominent physiographic features of major outcrops of high-quality knappable stone, leading some scholars to suggest that Clovis populations were tethered to quarries; that is, their mobility was shaped, to an unknown but presumably significant amount, by the need to periodically revisit these sources and replenish their supply of toolstone.”

In trying to understand the prehistory of North America, what is the significance of Clovis? For many years, there were archaeologists who promoted a “Clovis First” hypothesis which saw the Clovis people as the first Americans. Subsequent data from archaeology as well as from DNA has not supported this concept.

Since some Clovis artifacts were associated with megafauna kill sites and, furthermore, the Clovis points seems to be ideally suited for the hunting of this type of game, the stereotypic image of Clovis as mammoth-hunting people was developed. While there were times when Clovis hunters killed megafauna, such as mammoths, the archaeological record shows that Clovis peoples harvested many different food and fiber resources.

Since the time period for Clovis roughly corresponds to the period in which the North American megafauna went extinct, there has been some speculation about the role of Clovis hunting in this extinction. In their chapter in North American Archaeology, J.M. Adovasio and David Pedler write:

“Although some of these populations undoubtedly could, and in fact did, kill Pleistocene megafauna, a detailed analysis of all the alleged Clovis era kill sites definitively indicates that the available evidence does not support a significant or, indeed, detectable Clovis role in the extinction process.”

One way of looking at Clovis is to view it as a technology which was widely used by many different ancient American Indian cultures. There was no single Clovis culture which was unified by language, religion, and social organization.

More Ancient America

Ancient America: Kennewick Man (The Ancient One)

Ancient America: Windust Phase Indian Artifacts (Photo Diary)

Ancient America: Stone Quarries

Ancient America: The Avonlea Complex

Ancient America: Occupation of Paisley Caves in Oregon

Ancient America: Hunting Tools in British Columbia

Ancient America: Hunting Mastodons

Ancient America: Medicine Wheels