I remember the first time I saw the photo above. I thought about the hundreds of times I had seen “Rosie the Riveter,” who became the symbol for World War II women workers, and whose image was adopted by the feminist movement. Rosie was white. This woman was not.

I knew black women worked in war factories. My mom worked in a parachute factory in Maryland during the war. I hadn’t seen photos of them either, though I finally tracked one down.

I didn’t grow up with the idea that women were housewives who stayed home, and that going out of the home to work was something extraordinary because of wartime. The women in my family worked. They worked from sun-up to past sundown when they were enslaved, and after emancipation they worked as domestics, nannies, cooks, seamstresses, hairdressers, nurses, and schoolteachers. My college-educated great aunt Martha was a barber in the Woodward & Lothrop department store in D.C. (which was affectionately known as ‘Woodies’), the first black woman to hold that job. She was applauded by white people for ‘breaking a barrier’ and as a credit to her race and gender. I always thought it would have been more just had she been given a job as an educator, because of her training.

The women I knew who ‘stayed home’ were often taking care of the children of family and neighbors who did work, providing off-the-books day care.

I didn’t grow up with the idea that black men didn’t work. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) explores the history of the “shiftless and lazy stereotype” of black people.

Decades-old ephemera and current-day incarnations of African American stereotypes, including Mammy, Mandingo, Sapphire, Uncle Tom and watermelon, have been informed by the legal and social status of African Americans. Many of the stereotypes created during the height of the trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and were used to help commodify black bodies and justify the business of slavery. For instance, an enslaved person, forced under violence to work from sunrise to sunset, could hardly be described as lazy. Yet laziness, as well as characteristics of submissiveness, backwardness, lewdness, treachery, and dishonesty, historically became stereotypes assigned to African Americans.

These stereotypes, still perpetrated by a class of white people who have been determined to keep black folks down, made no sense to me. Working on a story for Black Kos two weeks ago, I came across this transcription of a 1968 CBS television interview with a woman in Charleston, South Carolina, describing her perception of the black workers on her family estate:

Mrs. Lionel Leg:

So Daisy was my little playmate, my maid, my friend, and the daughter of old Catherine, who was a cook that we adored. So all those years we played together and everyone was happy. We never heard of all these things we hear about today. And there were nearly a hundred, enormous rice plantation with many animals around, and a beautiful old house and about a hundred Colored people there. But we loved them. They were our friends, and then it’s no disgrace to say they’re like children. When we say they are like children, it’s because they are like happy children, some of them, because they like to sit in the sun rather than work hard, and they’d rather play than work.

Interviewer:

If you could, would you paint a picture for us of what it was like on the plantation in your early days.

Mrs. Lionel Leg:

It was a lovely happy time, living in open spaces with many lovely Colored people and animals and flowers and fields. My father had everything thoroughbred, from the pigs, horses, the dogs and the people had to be thoroughbred. And we would get into a buggy with him and drive to the plantation from what we call the pine land, where we lived. And we would spend, every Saturday this was, we would spend the day, and old Fortune, I can see him now, he would give us dinner. And we would have a heavenly time. And old April, he was the dairyman, that’s all he did, all he did was to skim the cream off of these great big boards of clabber and put them in the wooden churn and churn this marvelous fresh butter. That was April’s job. He didn’t do anything else, but love us and and skim the cream.

This Gone With the Wind fantasy of black plantation workers as happy children who ‘would rather play than work’ has morphed into ‘blacks on welfare’ who spend their time in ‘urban ghettos’ killing each other, glorying in ‘thug-life’, who ‘take’ from the rightfully indignant tax-paying, hard-working, white working-class, stoking racial resentments and ultimately playing a major role in bringing us Donald Trump. That same racist theme is used to blackanize working-class immigrants—with or without papers—who instead of being appreciated for toiling in our fields and factories doing hard labor are demonized as criminals, drug-dealers, and rapists.

My dad worked; sometimes at three jobs, and before he finally got his GI benefits and could go back to school and get a college degree, he was an actor, waited tables, and worked on trains. His dad was a chauffeur, and later a postal worker. My mom’s dad was a Pullman porter who worked long shifts and put his younger siblings through college in the decades after slavery ended. Their parents were slaves. Enslaved people worked—hard.

Most of the people in my family with college degrees worked in jobs not commensurate with their level of education—some in the post office, others in fairly low-level government jobs that didn’t pay a whole lot. The ‘black middle class’ is, in reality, a working class.

On this Labor Day weekend, as people gather for the last holiday of the summer season and students prepare to head back to school, there will also be parades and events celebrating unions and workers. Politicians on the stump will make speeches and those running for office will ‘celebrate the working class’ and ‘hard-working Americans,’ and oftentimes those speeches are targeted at and reference white people. When they talk about ‘the poor,’ they mean us. But ‘blue-collar’ is code for white-necks.

When I heard

these comments from Sen. Bernie Sanders after the 2016 election, I cringed and then got pissed off:

Donald Trump "very effectively" tapped into "the anger and angst and pain that many working class people are feeling," the Vermont independent senator who challenged Clinton in the Democratic primary said on "CBS This Morning."

"I think that there needs to be a profound change in the way the Democratic Party does business," Sanders said. "It is not good enough to have a liberal elite. I come from the white working class, and I am deeply humiliated that the Democratic Party cannot talk to where I came from."

I’m hearing similar rhetoric from some of our candidates this time around, including Joe Biden, Amy Klobuchar, and Pete Buttigieg. When I hear them target ‘liberal elites’ or ‘coastal elites’ I hear ‘rich white people.’ When they segue into those who ‘really count’ glorifying ‘the rust belt,’ they sure as hell ain’t talking about us—though we are there, too. ‘Economic populism’ as it plays out in real time is slanted toward the party ‘getting white people back again.’ There is little or no mention of the fact that the black working class is backing Democrats and helped sweep Democrats back into power in the House in 2018.

So on this Labor Day weekend, I’d like to share some thoughts about black workers and black labor, past and present.

After emancipation, ‘freedom’ didn’t mean you were free to not work. We were free to starve. Freedom often meant the state found a way to enslave you again.

Take the case of black coal miners. (I always see miners depicted as ‘white,’ too.)

African Americans have been mining coal and fighting bosses for over 200 years. Slaves were working in coal mines around Richmond, Va. as early as 1760. During the Civil War, a thousand slaves dug coal for 22 companies in the “Richmond Basin.” Black miners were expected to load four or five tons of coal. Slaves able to fill this quota were fed supper. Those who couldn’t were whipped.

Slavery in the mines didn’t end after the war in 1865. For decades prisoners convicted of “vagrancy” and “loitering” worked as virtual slaves for private outfits in Alabama, Georgia and Tennessee. From 1880 to 1904, 10 percent of Alabama’s state budget was paid by leasing prisoners to coal companies. African Americans accounted from 83 percent to 90 percent of these slave miners in Alabama. Sixty-nine percent of Tennessee prisoners digging coal in 1891 were Black. Some poor whites were railroaded to jail too. Conditions were horrendous in these convict mines. Nearly one out of ten prisoners died annually at the Tracy City, Tenn. mine operated by the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company (TCI). TCI was bought by United States Steel in 1907. USS continued to operate TCI’s mines in Alabama for another 20 years. Reparations are owed by USS and the JPMorgan/Chase Bank whose financial ancestor set-up this steel Goliath as the first billion-dollar corporation in 1900.

I don’t remember ever reading any of this history in my schoolbooks when we covered the rise of unions and the (white) labor movement.

For the history of blacks and labor, rather than rewrite what I’ve already posted here to Daily Kos, I’m republishing parts of my earlier stories.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Labor Day, the labor movement, and black Americans

Many working people across the United States are enjoying a three-day weekend thanks to

Labor Day. But sadly, it has become more of a retail holiday and a marker for the end of summer than a celebration of workers and organized labor. Even those who do honor workers and unions rarely explore the historical links between the

Pullman Strike of 1894 and the

black Pullman porters who could not strike—because they weren't allowed in a whites-only union.

In an op-ed for The Grio, Theodore R. Johnson wrote about how Labor Day was born:

Labor Day was nationally established after the Pullman Strike of 1894 when President Grover Cleveland sought to win political points by honoring dissatisfied railroad workers. This strike did not include porters or conductors on trains, but for the black porters, racism fueled part of the workers’ dissatisfaction, and was never addressed. Pullman porters were black men who worked in the trains’ cars attending to their mostly white passengers, performing such tasks as shining shoes, carrying bags, and janitorial services. During this period, this profession was the largest employer of blacks in the nation and constituted a significant portion of the Pullman company’s workforce, yet blacks were not allowed to join the railroad worker’s union.

Being excluded from the right to even fight for fair work and wages, the Pullman porters formed their own union called the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters, the first black union, and A. Philip Randolph was its first president. That name should sound familiar: the first planned March on Washington was Randolph’s brainchild. Set to take place in the 1940s, this demonstration was called off weeks before its kick-off date because President Roosevelt met with Randolph and other civil rights leaders in 1941, and signed an order barring racial discrimination in the federal defense industry. Roosevelt did so to stop the march from happening.

In spite of a history of exclusion, black Americans are the group that view unions most favorably, according to Pew research:

Across demographic groups, there are wide differences in overall favorability ratings of labor unions. Among blacks, who are more likely than other racial and ethnic groups to be union members, 60% hold a favorable view of unions; by comparison, 49% of Hispanics and 45% of whites view unions favorably.

Black Americans also have the highest

rate of union membership:

Among major race and ethnicity groups, black workers had a higher union membership rate in 2014 (13.2 percent) than workers who were white (10.8 percent), Asian (10.4 percent), or Hispanic (9.2 percent).

Black workers have fought to organize, even in the face of racism. When not allowed in white unions, they organized their own.

Let's examine that history.

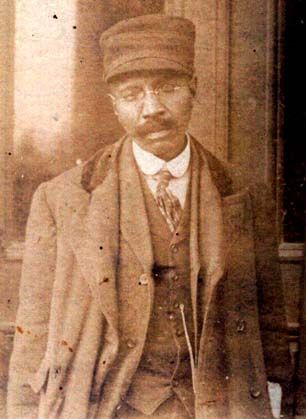

W.E.B Du Bois

W.E.B Du Bois

W.E.B. Du Bois

In March 1918, black scholar and activist

W.E.B. DuBois wrote

The Black Man and the Unions:

I am among the few colored men who have tried conscientiously to bring about understanding and co-operation between American Negroes and the Labor Unions. I have sought to look upon the Sons of Freedom as simply a part of the great mass of the earth’s Disinherited, and to realize that the world movements which have lifted the lowly in the past are opening the gates of opportunity to them today are now of equal value for all men, white and black, then and now.

I carry on the title page, for instance, of this magazine the Union label, and yet I know, and everyone of my Negro readers knows, that the very fact that this label is there is an advertisement that no Negro’s hand is engaged in the printing of this magazine, since the International Typographical Union systematically and deliberately excludes every Negro that it dares from membership, not matter what his qualifications.

Even here, however, and beyond the hurt of mine own, I have always striven to recognize the real cogency of the Union argument. Collective bargaining has, undoubtedly, raised modern labor from something like chattel slavery to the threshold of industrial freedom, and in this advance of labor white and black have shared.

I have tried, therefore, to see a vision of vast union between the laboring forces, particularly in the South, and hoped for no distant day when the black laborer and the white laborer, instead of being used against each other as helpless pawns, should unite to bring real democracy in the South.

On the other hand, the whole scheme of settling the Negro problem, inaugurated by the philanthropists and carried out during the last twenty years, has been based upon the idea of paying off black workers against white. That it is essentially a mischievous and dangerous program no sane thinker can deny, but is peculiarly disheartening to realize that it is the Labor Unions themselves that have given this movement its greatest impulse and that today, at last, in East St. Louis have brought the most unwilling of us to acknowledge that in the present Union movement, as represented by the American Federation of Labor, there is absolutely no hope of justice for an American of Negro descent.

Personally, I have come to this decision reluctantly and in the past have written and spoken little of the closed door of opportunity, shut impudently in the faces of black men by organized white workingmen. I realize that by heredity and century-long lack of opportunity one cannot expect in the laborer that larger sense of justice and duty which we ought to demand of the privileged classes. I have, therefore, inveighed against color discrimination by employers and by the rich and well-to-do, knowing at the same time in silence that it is practically impossible for any colored man or woman to become a boiler maker or book binder, an electrical worker or glass maker, a worker in jewelry or leather, a machinist or metal polisher, a paper maker or piano builder, a plumber or a potter, a printer or a pressman, a telegrapher or a railway trackman, an electrotyper or stove mounter, a textile worker or tile layer, a trunk maker, upholster, carpenter, locomotive engineer, switchman, stone cutter, baker, blacksmith, booth and shoemaker, tailor, or any of a dozen other important well-paid employments, without encountering the open determination and unscrupulous opposition of the whole united labor movement of America. That further than this, if he should want to become a painter, mason, carpenter, plasterer, brickmaster or fireman he would be subject to humiliating discriminations by his fellow Union workers and be deprived of their own Union laws. If, braving this outrageous attitude of the Unions, he succeeds in some small establishment or at some exceptional time at gaining employment, he must be labeled as a “scab” throughout the length and breadth of the land and written down as one who, for his selfish advantage, seeks to overthrow the labor uplift of a century.

At the National Archives and Records Administration, James Gilbert Cassedy provides an overview of research materials and records on

African Americans and the American labor movement:

The formation of American trade unions increased during the early Reconstruction period. Black and white workers shared a heightened interest in trade union organization, but because trade unions organized by white workers generally excluded blacks, black workers began to organize on their own. In December 1869, 214 delegates attended the Colored National Labor Union convention in Washington, D.C. This union was a counterpart to the white National Labor Union. The assembly sent a petition to Congress requesting direct intervention in the alleviation of the "condition of the colored workers of the southern States" by subdividing the public lands of the South into forty-acre farms and providing low-interest loans to black farmers. In January 1871, the Colored National Labor Convention again petitioned Congress, sending a "Memorial of the Committee of the National Labor Convention for Appointment of a Commission to Inquire into Conditions of Affairs in the Southern States."

More examples can be found in this rundown of

racism in the labor movement:

The Knights of Labor were racially inclusive, but many AFL unions kept out blacks.

Racial divisions among workers were often used to break strikes and undermine solidarity.

The early Knights of Labor actively accepted and organized black workers at a time when racism in America was intense. The AFL also started out in the 1880s with a nondiscrimination policy, but founder Samuel Gompers later came to see blacks as a "convenient whip placed in the hands of the employers to cow the white man." Fear that black workers would take whites' jobs haunted the labor movement for generations.

Employers did capitalize on racial divisions by recruiting black workers as strikebreakers. In a 1917 incident, employers in East St. Louis, Illinois, recruited southern blacks to take jobs for low pay to drive wages down. White workers organized a whites-only union in response. Racial tensions mounted and in July an attempt to drive blacks from their neighborhoods led to a riot in which 40 blacks and 9 whites were killed.

The AFL craft unions became solidly racist. In 1902 W.E.B. Du Bois, the influential black spokesman and historian, found that 43 national unions had no black members, and 27 others barred black apprentices, keeping membership to a minimum. Du Bois spoke against both "the practice among employers of importing ignorant Negro-American laborers in emergencies" and "the practice of labor unions of proscribing and boycotting and oppressing thousands of their fellow toilers." These policies of the unions were self-defeating. By refusing to admit blacks, they were assuring that there remained a group of workers that employers could turn to in order to bring down wages or to apply pressure during strikes. It wasn't until later in the twentieth century that union leaders began to look beyond their own prejudices to see that solidarity across racial lines made sense.

An important book which gives a narrative perspective on this history is:

Black Workers Remember: An Oral History of Segregation, Unionism, and the Freedom Struggle by

Michael Keith Honey.

The labor of black workers has been crucial to economic development in the United States. Yet because of racism and segregation, their contribution remains largely unknown. Spanning the 1930s to the present, Black Workers Remember tells the hidden history of African American workers in their own words. It provides striking firsthand accounts of the experiences of black southerners living under segregation in Memphis, Tennessee. Eloquent and personal, these oral histories comprise a unique primary source and provide a new way of understanding the black labor experience during the industrial era. Together, the stories demonstrate how black workers resisted racial apartheid in American industry and underscore the active role of black working people in history.

The individual stories are arranged thematically in chapters on labor organizing, Jim Crow in the workplace, police brutality, white union racism, and civil rights struggles. Taken together, the stories ask us to rethink the conventional understanding of the civil rights movement as one led by young people and preachers in the 1950s and 1960s. Instead, we see the freedom struggle as the product of generations of people, including workers who organized unions, resisted Jim Crow at work, and built up their families, churches, and communities. The collection also reveals the devastating impact that a globalizing capitalist economy has had on black communities and the importance of organizing the labor movement as an antidote to poverty. Michael Honey gathered these oral histories for more than fifteen years. He weaves them together here into a rich collection reflecting many tragic dimensions of America's racial history while drawing new attention to the role of workers and poor people in African American and American history.

Memphis Sanitation Strikers carried "I AM A MAN" posters.

Jacqueline Jones wrote

a detailed review of the book for

The American Prospect:

It is one of the great ironies of American labor history that enslaved workers toiled at a wider variety of skilled tasks than did their descendants who were free. Slave owners had an economic incentive to exploit the multifaceted talents of blacks in the craft shop as well as in the kitchen and field. But after emancipation, whites attempted to limit blacks to menial jobs. Throughout the late nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, blacks as a group were barred from machine work within the industrial sector, and from white-collar clerical and service work. "Modernization" wore a white face.

The interviews contained in this volume shine a harsh light on the nuts-and-bolts scaffolding of American workplace apartheid. Eyewitness testimony reveals not only the political economy that undergirded racial segregation on the job, but also the wide range of tactics on the part of African-American labor organizers who resisted it. Focusing on the city of Memphis, Tennessee, editor Michael Honey has assembled a story told through more than two dozen voices, a story about African-American men and women workers who literally risked their lives on the shop floor, day in and day out, trying to provide for their families.

She points out some of the harsh truths revealed by the interviews:

Readers who pick up Black Workers Remember hoping to find evidence of interracial solidarity on the job will be sorely disappointed. There are no white heroes in this book. White men came to work each day prepared to do physical battle with black men, and took their fight outside the workplace if they felt they had to. White women tended to be less physical but just as mean in their behavior toward black women. Toward black men, they could level accusations (of rape, lewdness) that were downright deadly.

During the 65-day strike of municipal sanitation workers in 1968, black workers wedded union activism with civil rights protests in an effort to defy the "plantation mentality" of Mayor Henry Loeb, one of the worst of Memphis's racist, anti-union employers. (In the city as a whole, nearly six out of 10 black people lived below the poverty line.) It was only with the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., on April 4 that public opinion finally pressured Loeb to recognize American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Local 1733.

Black radical activists embraced class struggle. They combined it with an ideology that grew out of the black power movement and pushed toward revolutionary nationalism. The U.S. auto industry became the eye of the storm. This was chronicled in

Detroit: I Do Mind Dying—A Study in Urban Revolution.

Since its publication in 1975, this book has been widely recognized as one of the most important on the black liberation movement and labor struggle in the United States. Detroit: I Do Mind Dying tells the remarkable story of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement, based in Detroit, and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, two of the most important political organizations of the 1960s and 1970s. The new South End Press edition makes available the full text of this out-of-print classic -- along with a new foreword by Manning Marable, interviews with participants in the League, and reflections on political developments over the past three decades by Georgakas and Surkin.The new edition includes commentary by Detroit activists Sheila Murphy Cockrel, Edna Ewell Watson, Michael Hamlin, and Herb Boyd. All of them reflect not only on the tremendous achievements of DRUM and the League, but on their political legacy -- for Detroit, for U.S. politics, and for them personally.

In the

foreword,

Manning Marable wrote:

By 1968, more than 2.5 million African-Americans belonged to the AFL-CIO. Yet the vast majority of black workers were marginalized and alienated from labor's predominantly white conservative leadership. In 1967, black militant workers at Ford Motor Company's automobile plant in Mahwah, New Jersey, initiated the United Black Brothers. In 1968, African-American steelworkers in Maryland established the Shipyard Workers for Job Equality to oppose the discriminatory policies and practices of both their union and management. Similar black workers' groups, both inside and outside trade unions, began to develop throughout the country. The more moderate liberal to progressive tendency of this upsurgence of black workers was expressed organizationally in 1972 with the establishment of the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists.

A much more radical current of black working-class activism developed in Detroit. Only weeks following King's assassination, black workers at the Detroit Dodge Main plant of Chrysler Corporation staged a wildcat strike, protesting oppressive working conditions they called "niggermation." The most militant workers established DRUM, the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement. DRUM soon inspired the initiation of other independent black workers' groups in metro Detroit, such as FRUM, at Ford's massive River Rouge plant, and ELRUM, at Chrysler's Eldon Avenue Gear and Axle plant. Other RUMs were developed in other cities, from the steel-mills of Birmingham to the automobile plants of Fremont, California, and Baltimore, Maryland. The Detroit-based RUMs coalesced in the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, which espoused a Marxian analysis of black working people's conditions, calling for a socialist revolution against the oppression of corporate capitalism.

Similar unity movements were formed in other industries. Most notable was health care, with the formation of HRUM (Health Revolutionary Unity Movement) in New York City. This would have a ripple effect on SEIU and 1199. Many of the organizers currently working for SEIU were forged in the struggles from that time period and were members of HRUM, the Black Panther Party, and the Young Lords Party.

Black communities and other communities of color across the nation are clearly at the bottom of the economic totem pole in the U.S., and embrace unions as a vehicle for economic justice in the workplace. Still, there remains the residual echo of distrust when politicians speak out about economic inequality.

Some of these issues were explored in a post I wrote four years ago (*note, now eight years ago):

I've come to believe that this "fuzzy middle" myth that has no real meaning in relationship to power hierarchies or dynamics is probably one of our greatest obstacles against working for meaningful change and redistribution of wealth. In the context of social stratification here in the United States, the categories of upper, middle and lower class are devoid of links to actual labor but seem to only reflect consumerist ideals. Class and status have become muddled. You are what you consume or drive.

To make matters more difficult, "race" has deeply embedded class connotations that are almost caste-like. So when the term "worker" is used along with code like "blue collar" to describe a sector of the population we almost automatically visualize "white worker," excluding those blacks, latinos, native americans and asians who are a large part of the U.S. labor force. Whereas when we say "poor" or "welfare" images of blacks and browns come to mind. "Immigrant" is the dog whistle for Mexican or "illegal" and few think of agricultural workers as foundational to our survival. A far cry from the days when we on the left supported the organizing struggles of the United Farm Workers.

Politicians from both parties invoke "Main Street" daily in an appeal to voters from this fuzzy middle. Only since the revolt in Wisconsin have we begun anew to frequently employ rhetoric invoking and defending the rights of "workers" to organize and protect their labor.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This was a commentary I wrote for

Black Kos, which sadly not enough people who read Daily Kos, follow or read.

The union that built the black middle class

One of the books I suggest you read if you are interested in both black history and sociology and the development of the labor movement is Rising from the Rails: Pullman Porters and the Making of the Black Middle Class, by Larry Tye.

Although Tye focuses on Pullman porters and the formation of the black middle class, his analysis of class perceptions and race relations reverberates to the current day. Following Reconstruction, industrialist George Pullman took advantage of the limited opportunities available for freedmen, hiring and exploiting blacks--the darker the better--to serve as porters on his railroad. The porters suffered low wages, long hours, and weeks if not months away from home. In addition, they were expected to adopt a servile demeanor to provide comfort to the mostly white patrons of the Pullman sleeping cars. But the upside was employment, travel, and middle-class values and opportunities. Moreover, the fight for union recognition through A. Phillip Randolph's leadership was the basis for progress for blacks during the pre-civil rights era. The porters' labor dispute and efforts to include blacks in more favorable positions in the war industry led to the first march on Washington. Tye also explores the tension between the perception of Pullman porters as docile servants and their challenge to the status quo. Vernon Ford

James A. Miller, professor of English and American studies and director of Africana studies at George Washington University, reviews Tye's book in “

A quiet route to revolution: Pullman porters played role as ‘agents of change’:

Tye depicts the struggle of the porters in heroic terms, casting them as the vanguard of a black community seeking to negotiate its relationship to an American society whose terms, rituals, and etiquette -- at least in the decades following the Civil War -- remained remote and unfamiliar: "Porters were agents of change. . . . They carried radical music like jazz and blues from big cities to outlying burgs. They brought seditious ideas about freedom and tolerance from the urban North to the segregated South. And when white riders left behind newspapers and magazines, porters picked up bits of news and new ways of doing things, refining them in each place they visited, and leaving behind a town or village that was a bit less insular and parochial."What they saw and read changed them, too. It made porters determined that their children would get the formal learning they had been denied. . . . Through their time on the train these black porters learned the ways of a white world most had only vague exposure to before, coming to know how it worked and how to work with it."

Tye's desire to place a human face on these workers is very much at the heart of "Rising From the Rails." Drawing upon extensive and meticulous research -- as well as in-depth interviews with 40 or so former porters and their families -- he depicts the absorbing saga of the Pullman porter, a story firmly rooted in the dynamic growth of the American railroad in the years following the Civil War. It is a tale populated by larger-than-life figures like Pullman, the visionary and ruthless capitalist whose unconventional tactics and attitudes qualified him, in Tye's view, as a racial "moderate if not a reformer"; Robert Todd Lincoln, the son of the Great Emancipator, who presided over an era marked by both unprecedented growth and labor repression at the Pullman Co.; and A. Philip Randolph, "Saint Philip," the eminent and outspoken Socialist and labor leader who -- along with Milton P. Webster, Ashley L. Totten, and C. L. Dellums -- spearheaded the effort that led to the triumphant emergence of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in 1937.

The story does not end there, for Tye makes a compelling case for the intricate connections between the porters' struggles for economic justice and the quickening pace of the civil rights movement in the 20th century -- from the formation of the National Negro Congress in the mid-1930s to Randolph's threatened 1941 march on Washington to the 1963 march on Washington, and beyond. Throughout, Tye sustains our interest, weaving together several levels of narrative while keeping the stories of ordinary porters squarely at the center. The result is a lively and engaging chronicle that adds yet another dimension to the historical record.

Tye's book later became the basis for a documentary film with the same name.

Too often when we discuss the civil rights movement, we don't tie it in with the labor movement and the first powerful black union: the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

You won't have to go very far or dig very deep to find black Americans who can tell you stories about fathers or grandfathers or uncles who worked as Pullman porters and waiters.

My grandfather, my mom's dad Dennis Presley Roberts, is one of those stories.

Born on June 24, 1874, in Loudoun County, Virginia, he was the son of two former slaves. His mother swore that all of her children would become educated, and Dennis took on that task not only for himself, but for all his brothers and sisters. He learned to read and write in a one-room schoolhouse, and migrated to nearby Washington, D.C., to work as a waiter and attend Wayland Seminary (which merged with Virginia Union) which he graduated from in 1897. Not content to become (as he put it) a "jack-leg preacher," he decided not to further his education, and the economic pressures to assist his younger brothers and sisters pushed him to taking a job on the railroad.

Dennis was canny about finance, and saved his salary and every tip from the elite whites he waited on daily to buy houses. Recognizing the need for black-owned apartments in the growing black metropolis of D.C., Dennis bought first one building, and then another. One of the buildings he owned was at 1523 T Street NW. (I had to laugh when I looked up what that building is worth now: $1,132,020). As the self-appointed patriarch of the family he was a bit of a martinet. Just like the trains ran on time, granddaddy Dennis did everything on a schedule. He wore a watch on a chain, which he constantly referred to. He also brooked no talk back. He ordered the lives of his siblings, telling John to teach, Joseph to go to medical school, James to become a dentist, and proclaiming that the girls, Hannah and Martha, would go to teachers college. He helped them all pay their school fees.

My Grandfather: Dennis Presley Roberts

My Grandfather: Dennis Presley Roberts

He was soft-spoken, and always impeccably dressed. My mom says she never saw him in his shirtsleeves, though he did have a smoking jacket he wore when he was "relaxed." In 1907 he married a beautiful young woman, also from Loudoun County, who was working as a domestic in New Jersey, and soon moved his young family to New London ,Connecticut, since by that time he was working on the New York to New Haven line. After the birth of his first four children, he relocated the family to the Bronx, where his wife died after giving birth to my mom. Undaunted, he refused to split up his children and parcel them out to different relatives. Instead, he ordered his widowed sister Martha to leave D.C., used his funds to help establish his younger brother the doctor in Philadelphia, helping him buy a large home, and moved Martha and the children in with Dr. Joe. Joe's practice flourished, and as a consequence my mom was raised in a home with a cook, a laundress, and two maids. Granddaddy Dennis bought another building in Philly with an ice cream parlor on the ground floor for Martha to run.

He never stopped working the trains. Once a month he would arrive in Philadelphia to "inspect" his children and monitor their schooling and manners. My mother remembers him ruefully stating that he would earn more money in tips if he adopted an uneducated speech pattern and obsequious attitude, but there was no way he was going to bend. He raised his children to be Negro and proud and to never cross a picket line. Family members of the porters got to travel the railroad free, and my mom used to go each summer down to D.C. from Philly, traveling under the watchful eye of his "brother" waiters and porters. It was like having a family that extended across the U.S.

His story is really no different than that of his brother porters. White passengers saw only black servants, never imagining that these men were buying property, sending their progeny to colleges and universities, and funding the growing civil rights movement. Their union, led by socialist A.Philip Randolph, would become a powerful voice for change, affecting not only the segregated labor movement, but the course of the nation.

There are many other books and films exploring the Pullman porter's lives and union movement. California Newsreel distributes Miles of Smiles, Years of Struggle, winner of four regional Emmy Awards, produced by Jack Santino and Paul Wagner. Jack Santino is the author of the book, Miles of Smiles, Years of Struggle – Stories of Black Pullman Porters.

Miles of Smiles chronicles the organizing of the first black trade union - the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. This inspiring story of the Pullman porters provides one of the few accounts of African American working life between the Civil War and World War II.

Miles of Smiles describes the harsh discrimination which lay behind the porters' smiling service. Narrator Rosina Tucker, a 100 year old union organizer and porter's widow, describes how after a 12 year struggle led by A. Philip Randolph, the porters won the first contract ever negotiated with black workers. Miles of Smiles both recovers an important chapter in the emergence of black America and reveals a key source of the Civil Rights movement.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

While I was assembling the bits and pieces I put together here today, I ran across a black woman telling the story of her family, and it resonated with me.

Maura Davis wrote forThe Atlantic: American Wealth Is Broken.

My family is a success story. We’re also evidence of the long odds African Americans face on the path to success.

That my grandfather built enough wealth to get us into that house but not enough to keep it is partially a result of how much the cards have been stacked against African American wealth-building for generations. When World War II ended, my grandfather was only 6, but the discriminatory distortions of the GI Bill are still visible in our family’s financial history. His father, aunt, and uncles were World War II veterans. Four of them were able to secure coveted government jobs. While this may have given them stability, it did not help them build long-term wealth to pass along. White veterans, however, were encouraged to go to college, where they graduated with degrees in subjects such as engineering, according to research by the journalist Edward Humes. Even though 49 percent of black veterans (compared with 43 percent of white veterans) took advantage of some sort of education or training offered through GI Bill benefits as of 1950, that didn’t always mean a college degree. Most African American veterans who exercised their education benefits after World War II ended up pursuing vocational training, as counselors who approved the benefits steered blacks into low-paying jobs or historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). At the time, HBCUs were underfunded and did not offer engineering programs. Short on space, they were forced to turn away up to 50,000 black veterans. Humes also pointed to a survey of 6,000 job placements in Mississippi during the fall of 1946: 86 percent of the skilled, professional, and semiskilled jobs went to white veterans.

My grandfather joined a union in 1956. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the National Labor Relations Act into law, policy makers drafted it to exclude agricultural and domestic workers, so black people made up less than 1 percent of union members. Black workers continued to struggle for equal treatment in unions: 31 affiliates of the American Federation of Labor explicitly excluded black workers at one point. Membership was nonetheless an important stepping stone for my grandfather. He gained entry only after his grandmother, a maid, persuaded her boss, the entrepreneur Charlie Willard, to hire her grandson. Willard helped him earn union membership and later made my grandfather a crew foreman. He got assigned to run the crew for Pennsylvania Hospital’s first professionally air-conditioned building. As my grandfather tells it, the hospital quickly poached him, offering him a full-time job and eventually promoting him to a position with a salary of $35,000.

Eventually my grandfather wanted more than a steady paycheck. Although he may not have thought about it at the time, he wanted to build wealth. So he started a side hustle installing air conditioners for restaurants, bars, and colleges. He branded white trucks with his name and hired a crew to help him fulfill orders while he was at the hospital. When the hospital discovered his other business, his boss gave him an ultimatum: his side hustle or his full-time job. He chose the side hustle. He recalls union companies early on working with their friends to secure low prices from suppliers, blocking him from getting projects. My grandfather’s story is one of success (this year his business turns 50) that also illustrates why black success is used to claim that the playing field in America is more level than it actually is. My grandfather made it, but does his success against all odds mean that it’s okay when everyone else faces those same odds and fails? A black family’s success story is reassuring proof that the system works. If my family could successfully climb upward, the argument goes, then the ones who can’t aren’t trying hard enough. They don’t have enough grit. But successful black people are also treated as extraordinary. Why? Because Americans know the system is broken.

In sharp contrast is this story of a hard-working woman, who in spite of her hard work is now homeless. She is “one of those people” who racists love to point a finger at. She is also one of those working people many politicians are not talking about.

I read it after I saw this tweet from Soledad O’Brien:

Brian Goldstone introduces this woman and her family:

Last August, Cokethia Goodman returned home from work to discover a typed letter from her landlord in the mailbox. She felt a familiar panic as she began to read it. For nearly a year, Goodman and her six children—two of them adopted after being abandoned at birth—had been living in a derelict but functional three-bedroom house in the historically black Peoplestown neighborhood of Atlanta. Goodman, who is 50, has a reserved, vigilant demeanor, her years trying to keep the kids out of harm’s way evident in her perpetually narrowed eyes. She saw the rental property as an answer to prayer. It was in a relatively safe area and within walking distance of the Barack and Michelle Obama Academy, the public elementary school her youngest son and daughter attended. It was also—at $950 a month, not including utilities—just barely affordable on the $9 hourly wage she earned as a full-time home health aide. Goodman had fled an abusive marriage in 2015, and she was anxious to give her family a more stable home environment. She thought they’d finally found one.

As a longtime renter, Goodman was acquainted with the capriciousness of Atlanta’s housing market. She knew how easily the house could slip away. Seeking to avoid this outcome, she ensured that her rent checks were never late and, despite her exhausting work schedule, became a stickler for cleanliness. So strong was her fear of being deemed a “difficult” tenant that she avoided requesting basic repairs. But now, reading the landlord’s terse notice, she realized that these efforts had been insufficient. When her lease expired at the end of the month, it would not be renewed. No explanation was legally required, and none was provided. “You think you did everything you’re supposed to do,” she told me, “and then this happens.”

Go read the whole thing.

Why am I including this story for Labor Day?

Because far too often, women like Cokethia Goodman are not the symbol of labor, of the “work hard and you will prosper” meme that will be trotted out across the nation this weekend.

Systemic racism combined with toxic sexism has warped the entire meaning of ‘the working class’ in the U.S. What we view as ‘the labor movement’ needs to become an ‘address systemic inequality and white supremacy movement.’

I write about black working people, and our history, from my perspective as a black woman. However, that does not mean I am ignoring the labor of other workers of color—especially women. We just celebrated Black Women’s Equal Pay Day — with a tweetstorm using hashtag #BlackWomensEqualPay (go take a look and see who participated) and the numbers for those women who labor for less are unconscionable.

Close your eyes, and visualize who you see when someone talks about ‘union workers’ and Labor Day.

Do you see a white guy in a hard hat?

Or do you see who I see?