The Great Basin Culture Area includes the high desert regions between the Sierra Nevada and the Rocky Mountains. It is bounded on the north by the Columbia Plateau and on the south by the Colorado Plateau. It includes southern Oregon and Idaho, a small portion of southwestern Montana, western Wyoming, eastern California, all of Nevada and Utah, a portion of northern Arizona, and most of western Colorado.

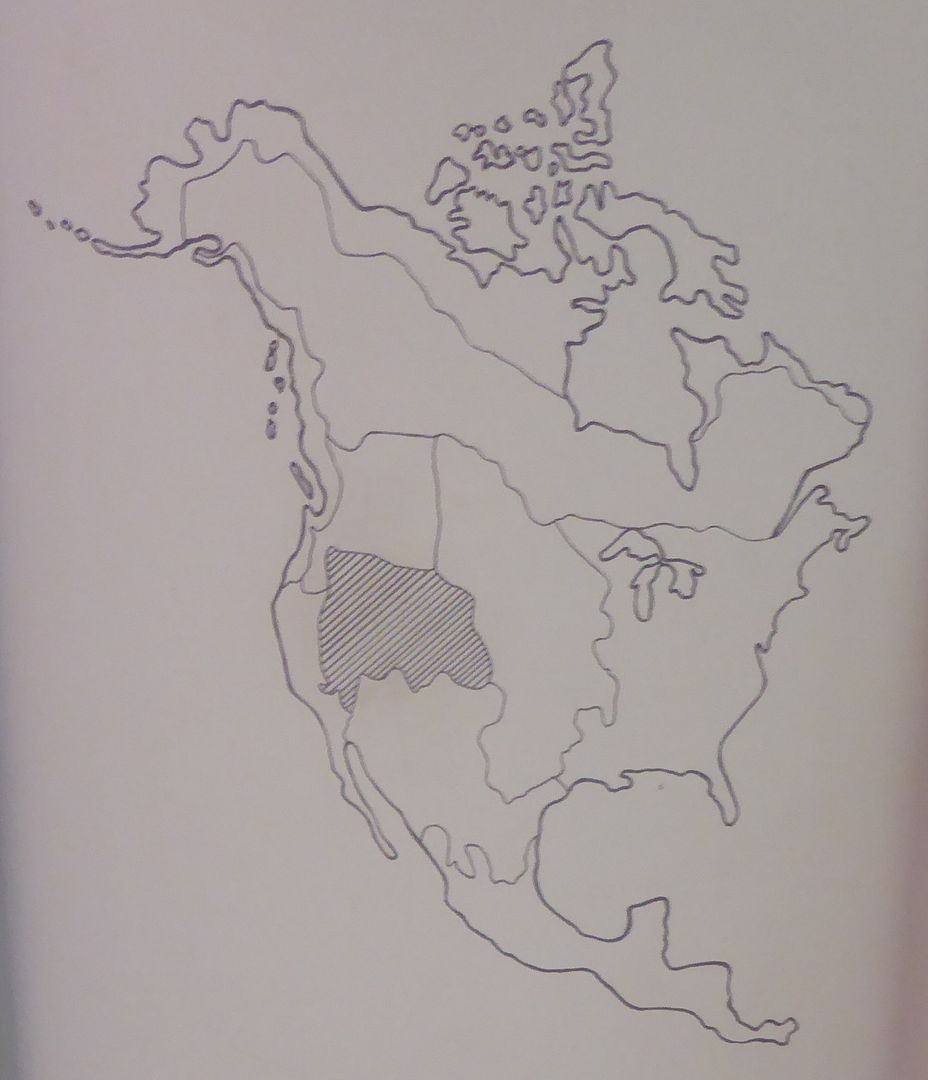

The shaded area is the Great Basin Culture Area. This is from a display in the Maryhill Museum.

The shaded area is the Great Basin Culture Area. This is from a display in the Maryhill Museum.

This is an area which is characterized by low rainfall and extremes of temperature. The valleys in the area are 3,000 to 6,000 feet in altitude and are separated by mountain ranges running north and south that are 8,000 to 12,000 feet in elevation. The rivers in this region do not flow into the ocean, but simply disappear into the sand.

The basic tribes of the Great Basin Culture Area include Bannock, Gosiute, Mono, Northern Paiute, Panamint, Shoshone, Southern Paiute, Washo, and Ute. Linguistically all of the Indian people of the Great Basin, with the exception of the Washo, spoke languages which belong to the Numic division of the Uto-Aztecan language family. The Numic languages appear to have divided into three sub-branches—Western, Central, and Southern—about 2,000 years ago.

In their chapter on the Great Basin in The Oxford Handbook of North American Archaeology, Christopher Morgan and Robert L. Bettinger report:

“Ethnographically, the region was inhabited by small, mobile bands of Ute, Paiute, and Shoshone hunter-gatherers who subsisted on a wide variety of plants and animals such as wild grass seeds, roots, rabbit, deer, bighorn sheep, insects, and especially piñon pine nut gathered in the fall.”

In his 1938 Bureau of American Ethnology Report, Basin-Plateau Aboriginal Sociopolitical Groups, anthropologist Julian Steward writes:

“Ritual was everywhere exceedingly limited and practically none attached to economic activities.”

The main rites of passage—birth, girl’s puberty, and death—were family affairs rather than tribal or communal ceremonies. According to Angus Quinlan and Alanah Woody, in an article in American Antiquity:

“Large-scale group rituals were largely absent, with the important exception of seasonal dances held when food supplies permitted.”

Writing about the Northern Shoshone in the Handbook of North American Indians, Robert Murphy and Yolanda Murphy write:

“The lack of elaborate ceremonial or of highly specialized religious practitioners was congruent with the nomadic and shifting nature of Shoshone society and with its egalitarianism.”

Among the Paiute, dancing in a circle is a way of opening the dancers to spiritual influence. By dancing along the path of the sun—clockwise to the left—the dancers symbolize the fact that the community lives through the circle of days.

Some of the ceremonies found among the people of the Great Basin are briefly described below.

Sweat Lodge

As in other culture areas, the sweat lodge was, and still is, an important part of spiritual life. The sweat lodge ceremony is perhaps the oldest of all ceremonies. With regard to the Owens Valley Paiute, Julian Steward reports:

“Band unity was somewhat expressed in and heightened by use of a communal sweat house.”

The sweat lodge ceremony is usually held in a special small lodge. Rocks are heated on an outside fire until they are red hot and then rolled or carried into the lodge. In total darkness, the sweat lodge leader sprinkles water on the hot stones creating steam and intense heat. The actual ceremony varies greatly according to tribal traditions and to the ceremonial leader.

In many cultural traditions, the sweat lodge ceremony is held in a special lodge and involves hot stones upon which water is sprinkled to create steam. This is, however, not always the case. In his chapter in A History of Utah’s American Indians, Dennis Defa reports:

“The Goshute sweat bath was done without water; hot rocks and coals were covered with earth and the patient would lie on top.”

Shoshone Bear Dance

The Shoshone Bear Dance was originally a hunting dance, which had nothing to do with hunting bears. Men and women would face each other in two long lines and dance in a back-and-forth manner. In one form of the dance, a drum is used while in another form an upside-down basket is scraped by a rasp stick.

Sun Dance

The Sun Dance originally evolved among the Plains Indians and during the early nineteenth century, it diffused to tribes in the Plateau and Great Basin Culture Areas. Often known as the Thirsty Dance, the participants would dance for several days, usually three or four, with no food or water. The ceremony is not about worshipping the sun or any particular deity. It is generally a renewal ceremony and for some of the participants it may involve a personal quest for spiritual power.

Among the Shoshone on the Wind River Reservation, the Sun Dance happens because of a dream. Yellow Hand, the visionary who brought the Sun Dance to the Shoshone, had a vision in which the ceremony was taught to him by a buffalo. Thus, each person who is called to the Sun Dance is there because of a personal dream.

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Christian missionaries and government officials were particularly offended by the Sun Dance, or at least, their perception of the Sun Dance. They viewed it as a form of “devil” worship and used it as evidence for outlawing all American Indian religious practices.

Mourning Ceremony or Cry

Among the Southern Paiute, the Mourning Ceremony or Cry is held from three months to a year after the death of a relative. During this ceremony, a number of items would be destroyed: buckskins, eagle feathers, rabbitskin blankets, nets, baskets, and weapons. According to anthropologists Isabel Kelly and Catherine Fowler, in their chapter in the Handbook of North American Indians: “The outlay for food and goods was enormous, hence such ceremonies were infrequent.” Relatives gave the ceremony so that they could sleep and eat well.

Among the Owens Valley Paiute, the Mourning Ceremony was usually held in the fall. During the ceremony, mourners’ grief was symbolically washed away. All of the dead from the previous year were commemorated by burning their personal articles.

Fall Festival

Among the Southern Paiute, the fall festival would unite several villages. The three- or four-day ceremony was planned and directed by a local village chief and was announced six to eight months in advance. Dances included the circle dance, a borrowed form of the Ute Bear Dance, and two special dances. The festival would conclude with the Mourning Ceremony.

Round Dance

For the Shoshone, Paiute, and other tribes, the Round Dance is both a ceremonial and social dance. The dance is often associated with prayers for health, for the welfare of the people, fish, and animals, and for the return of fish and other foods. Among the Northern Paiute the Round Dance was performed prior to the fishing season in May, the jackrabbit communal drives in November, and the pine nut harvests in the fall. According to anthropologist Michael Hittman, in his book Corbett Mack: The Life of a Northern Paiute, the Round Dance is performed by

“Northern Paiute men and women who gathered from far and wide, painting their faces and dancing till morning around a center pole to the instrumentless singing of ritual officiants.”

Among the Lemhi Shoshone, the round dance was traditionally done in the spring and in the fall. However, since the dance brought blessings, it could be held during any period of sickness or other trouble.

According to oral tradition, the Round Dance existed in the mythic past when Coyote ruled the world.

Father Dance

The Father Dance is an Eastern Shoshone ceremony which originated at the end of the 18th century. The dance was sponsored by a person who had dreamed it. The sponsor, assisted by two other people, then distributed sage to the dancers. The dancers, both men and women, formed a circle around the sponsor. The sponsor then gave 10 prayers and 10 prayer songs for the children’s health. During the prayers the dancers stood still and during the songs they danced.

The dance was usually held during a full moon and was conducted for three or four consecutive nights. At the end of the dance, the dancers shook disease away with their shawls and blankets.

The Father Dance is sometimes called the Shuffling Dance or the Ghost Dance.

Warm Dance

The Warm Dance was a Shoshone ceremony usually held in January. In her chapter in A History of Utah’s American Indians, Mae Parry writes:

“The object of the Warm Dance was to drive out the cold of winter and hasten the warmth of spring.”

Scalp Dance

Among the Northern Shoshone the Scalp Dance was a women’s dance. Men would beat the drums while the women, dressed in beaded outfits and carrying eagle feathers, danced around a scalp pole. Scalp dance songs were composed to reflect the success of the war party that was being celebrated.

Ghost Dance

The Ghost Dance of the Paiute prophet Wodziwob spread throughout the Great Basin tribes. According to Joseph Jorgensen, in his chapter in the Handbook of North American Indians:

“Wodziwob’s Ghost Dance religion of 1869 and the manifestations of that religion elsewhere in the Great Basin represented a synthesis of the traditional belief in visions, the traditional practice of circle dancing associated with antelope charming and other subsistence pursuits, and, perhaps a borrowing from Sahaptian or Salishan Indians of the Plateau and Northwest Coast of the belief in prophets, prophecies, and return of the dead.”

Food-Related Ceremonies

Among some of the Great Basin Indian tribes there were, and sometimes still are, ceremonies which focus on the gathering of wild food plants and on fishing. In general, the Indian people of the Great Basin tended to be highly mobile to utilize the diverse and scattered subsistence resources of the area. This mobility was not random nomadism but was timed to maximize the seasonal resources of numerous environmental niches within the area.

Much of the subsistence of the Great Basin groups depended on the gathering of wild plants. It is estimated that 30-70% of the Great Basin diet was based on plants. One of the important foods was the pine nut which ripens in late fall. Among some of the groups, Piñon Ceremonies would be held several months before harvesting the pine nut crop. Prayers would be offered to “set” the crop (the pine nut crop is unpredictable as each tree yields only once in 3-4 years). At the time of the harvest, there would be round dances and prayers of thanksgiving would be offered over the first seeds harvested. Among the Northern Paiute, the Pine Nut Festival is a five-day sacred rite which has the Round Dance as its centerpiece.

Among the Lemhi Shoshone, the Nuakin was a ceremony which asked for plentiful salmon, berries, and other foods.

For the bands living in the Snake River basin, the salmon was a key food source. In order to maintain proper relations with the salmon, and thus ensure the continuation of the salmon run, the Shoshone people would hold a feast, the First Salmon Ceremony, during which the first catch would be divided among the band members.

For the bands living in southern Idaho, the camas root was an important food source. Thus, the Camas Root Ceremony helped to ensure a good harvest and to maintain the reciprocal spiritual relationship between the camas and the Shoshone.

Indians 101

Twice each week Indians 101 explores American Indian topics. More about the Great Basin tribes from this series:

Indians 101: The Indian Tribes of the Great Basin Culture Area

Indians 101: Marriage Among the Great Basin Indian Nations

Indians 101: Children Among the Great Basin Indian Nations

Indians 201: Sacred Places in the Great Basin

Indians 101: The Horse and the Great Basin Indians

Indians 101: Great Basin Culture Area

Indians 101: Ute Spirituality

Indians 101: A Short Overview of the Ute Indians