The first North American furs were carried to European markets sometime prior to 1000 CE by Viking traders. By the eighteenth century, European traders were providing American Indians with a variety of manufactured goods in exchange for hides and fine furs. With the fur trade, American Indians were incorporated into the global economy. Trade was fueled in part by the European desire to obtain furs and tanned hides. The Europeans were impressed by the number of fur-bearing animals which they found. Many of these fur-bearing animals had already been trapped to extinction in many parts of Europe.

The French, English, Spanish, and Russians were actively engaged in trade during the eighteenth century. The Europeans carried out trade with corporations such as the London-based Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and the Montreal-based North West Company (Nor’westers), ad hoc groups, and sea captains. HBC established trading posts to which Indians brought their furs and hides to exchange for European goods, while other traders traveled to Indian villages to trade.

During the first part of the eighteenth century, the French fur trade was an instrument of French imperial policy. The trade was controlled by servants of the Crown and the prices offered to the Indians for their furs was intended to be generous enough to keep them from trading with the British. In their book Exploring the Fur Trade Routes of North America, Barbara Huck et al report:

“Until the Treaty of Paris brought their occupation to an end in 1763, the French dominated the fur trade, penetrating the continent more deeply than any other European nation.”

An important part of the French-Indian fur trade involved the marriage of the French fur traders into the Indian tribes. The French fur traders adopted many aspects of Indian culture and became as Indian as they were French. In his chapter on French exploration in North American Exploration. Volume 2: A Continent Defined, William Eccles writes:

“These marriage alliances were regarded favourably by the Indians, since they strengthened the bonds between the two races, but they were frowned on by the royal officials and the clergy, who maintained that the offspring of these marriages combined the worst features of both races.”

The marriage of the traders to Indian women were advantageous to both trade and diplomacy. They also resulted in interracial and intercultural families. In his book First Across the Continent: Sir Alexander Mackenzie, historian Barry Gough writes:

“The descendants of these families became a distinct and important people in Canadian history, the Métis.”

Following the pattern of French trading, the Nor’westers frequently married into the tribes of their trading partners. While not officially encouraged, the HBC traders also enhanced their trading relationships with intermarriage. Indian wives were referred to as “in-country wives” and some traders maintained several wives.

For eighteenth-century Europeans, beaver pelts were an important commodity. Historian James Axtell, in his book Beyond 1492: Encounters in Colonial North America, reports:

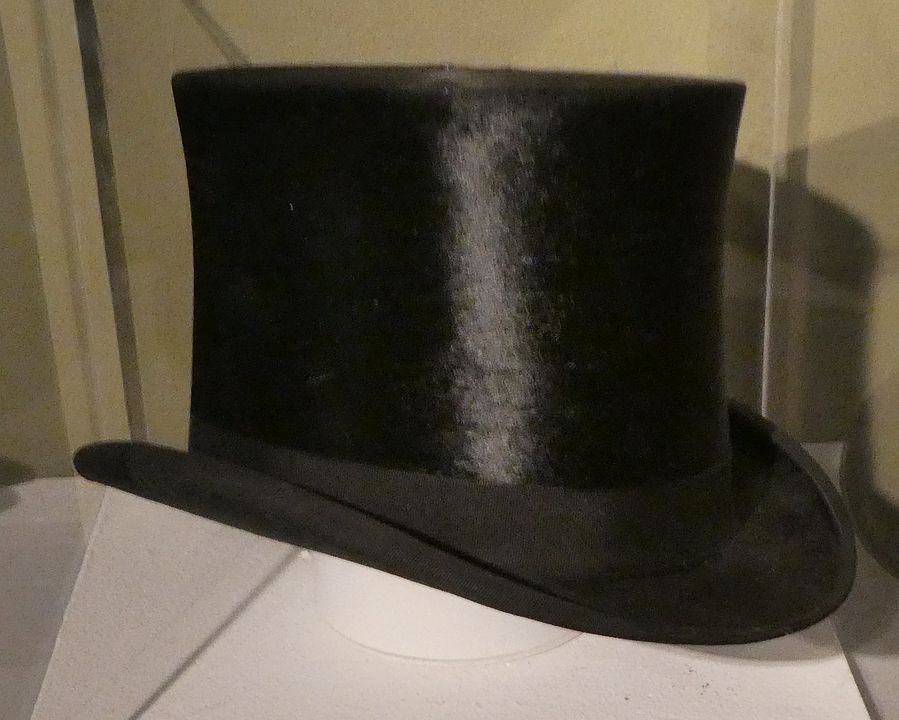

“Beaver, for which the natives had little use before the trade, became the best seller because of its soft, microscopically barbed underfur which was in great demand for the manufacture of broad-brimmed felt hats for Europe’s gentlemen.”

Thus, the fashion demands of a distant part of the globe brought change to Indian cultures. With regard to the beaver hat, Doug Whiteway, in his entry on the beaver hat in Exploring the Fur Trade Routes of North America, writes:

“The beaver hat originated in the 14th-century Russia, but stepped into the world stage with Sweden’s successes during the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). Swedish soldiers wore wide-brimmed hats with such romantic appeal that everyone had to have one.”

Doug Whiteway also writes:

“If Europeans had been satisfied with cloth caps, who knows what turns North American history might have taken? But Europeans wanted beaver hats and North America had beavers aplenty. And so a continent was invaded to serve a purpose we might consider frivolous—fashion.”

Shown above is a beaver hat on display in the Wenatchee Valley Museum in Wenatchee, Washington.

Shown above is a beaver hat on display in the Wenatchee Valley Museum in Wenatchee, Washington.

Shown above is a “made beaver”—a tanned beaver pelt—on display in Historic Fort Benton, Fort Benton, Montana.

Shown above is a “made beaver”—a tanned beaver pelt—on display in Historic Fort Benton, Fort Benton, Montana.

In addition to furs, the European traders also sought tanned hides, usually deerskin but also elk and moose. The hide trade was important as the European tanneries were unable to produce leather as supple and white as that produced by the Indians. In her chapter in Robes of Splendor: Native North American Painted Buffalo Hides, Anne Vitart notes:

“The cost of Indian leather, on the European market, was twice that of the regular leather from European tanneries.”

In her book Slavery in Indian Country: The Changing Face of Captivity in Early America, Christina Snyder reports:

“Beginning in the eighteenth century, a European cattle plague threatened the British leather industry, but American deerhides provided an acceptable substitute used by manufacturers in bookbinding, in saddles and saddlebags, and in deerskin breeches favored by American colonists. From 1700 to 1715, Indians supplied Charles Town merchants with 54,000 deerskins each year. The trade reached its peak in the mid-eighteenth century, when Native hunters provided upwards of 150,000 deerskins annually.”

The fur and hide trade was not just an international exchange between North America and Europe, but also included trade with Asia. On the Pacific Coast, by 1741 the Russians had found that sea otters were valuable in the Chinese market. In his book The Native People of Alaska, Steve Langdon writes:

“The discovery of millions of sea otter quickly prompted commercial efforts by independent fur trappers and traders of Cossack descent known as promyshlenniki.”

While trade along the Pacific coast and Hudson’s Bay allowed good access to sea-going ships, many traders also ventured deep into the interior of North America. By 1735, for example, French traders were trading with the Mandans in the Dakotas and had ventured west to the Rocky Mountains. In his book Astoria: John Jacob Astor and Thomas Jefferson’s Lost Pacific Empire, A Story of Wealth, Ambition, and Survival, Peter Stark writes:

“Culturally, the French held an advantage in the fur trade because they, unlike the English, had few qualms about intermarrying with Native Americans and acculturating to an Indian way of life. They learned to hunt deer and moose like the natives, fish, live in the woods, trap the abundant beaver, paddle hundreds of miles by birch bark canoes, or, in winter, make their way by snowshoe and toboggan.”

In eighteenth-century North America, rivers and lakes provided the transportation routes into the interior. One of the important tools of the trade was the use of birchbark canoes. In his book Northwest Passage: The Great Columbia River, William Dietrich reports:

“These craft were typically thirty-two feet long, five feet wide, and weighed only three hundred pounds when dry. Yet they could carry eight thousand pounds of crew and freight and had a draft of only eighteen inches.”

Shown above is a small birchbark canoe on display in Historic Fort Benton, Fort Benton, Montana.

Shown above is a small birchbark canoe on display in Historic Fort Benton, Fort Benton, Montana.

The paddlers, usually French Canadian and/or Indian, would paddle at a rate of 45 strokes per minute and average four miles per hour over an 18-hour day. Barbara Huck et al report:

“Though birchbark canoes, all of slightly different design, were made by many North American nations, the fur trade spread their use far beyond the ideal environment for constructing them. Fur brigades therefore often carried large rolls of birchbark or spruce root with them for mending or producing canoes.”

Moving from the Great Lakes into the Northwest, the fur traders used smaller canoes—usually under 26 feet in length—which were better suited to the maze of smaller lakes and rivers northwest of Lake Superior.

Indians 101

Twice each week—on Tuesdays and Thursdays—this series presents American Indian topics. More about the fur trade from this series:

Indians 101: The fur trade in Washington

Indians 101: The Fur Trade in Northwestern Montana, 1807-1835

Indians 101: Nor'westers and Indians in the Columbia Plateau

Indians 101: The Astorians and the Indians

Indians 101: Fur Trade in the Rockies, 1801 to 1806

Indians 101: Cultures in Contact on the Northern Plains

Indians 101: The Pacific Fur Company

Indians 101: The fur trade in 1821