The Hopi villages in Northern Arizona were off the beaten path for the early Spanish explorers and the later American settlers in the Southwest. As tourism began to increase in the Southwest during the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, driven by the Santa Fe Railway and the Fred Harvey Company, the Hopi village and Hopi culture seemed to be an exotic window into the indigenous past unmodified by European cultures. During the first part of the twentieth century Indians, and particularly Hopi Indians, were promoted as tourist attractions.

Off the Reservation

In 1905, the Fred Harvey Company completed the El Tovar hotel at the Grand Canyon to accommodate tourists brought in by the Santa Fe Railway. Near the hotel, Harvey Company built Hopi House, a three-story structure designed to look like a cluster of Hopi dwellings where guests were able purchase curios and watch Indians demonstrate their craft skills and dancing.

The famous Hopi potter Nampeyo and her family were among the first to live and work at Hopi House. The promotional material for one photograph reads: “These quaintly-garbed Indians on the housetop hail from Tewa, the home of Nampeyo, the most noted pottery-maker in all Hopiland” and concludes that “They are the most primitive Indians in American, with ceremonies several centuries old”

The use of the Hopi as a tourist attraction at the Grand Canyon did not work as smoothly as the non-Indian organizers had envisioned. According to Nampeyo’s biographer Barbara Kramer, in her book Nampeyo and Her Pottery:

“They expected mesa residents to leave their homes willingly upon request and to stay at Hopi House until replacements for them could be found.”

The Hopi were expected to make baskets and pottery for sale, to work around the store packing and cleaning, and to dance for the tourists at night.

In 1910, the Chicago Tribune sponsored a second United States Land and Irrigation Exposition in Chicago. The Santa Fe Railway and the Fred Harvey Company, promoting travel to the southwest, constructed a building for the Hopi. The Fred Harvey Company requested that the superintendent of the Hopi Reservation provide them with one family from each of the three Hopi mesas. The women were to make baskets and pottery and the men were to weave blankets, kilts, and sashes. The company asked that only two children be allowed to accompany each family and that the girls must have their hair done in whorls, that the men wear moccasins, velvet shirts, and bandanas around their foreheads, and that the women wear traditional Indian costumes.

In 1928, the Pacific Southwest Exposition in Long Beach, California, presented an Indian village resembling a pueblo which included Navajos and Hopis who were required to wear Plains Indian war bonnets. A sign at the entrance to the “authentic village” told the visitors that Indians are wards of the government. The Navajo and the Hopi are, of course, from the Southwest and their traditional cultures do not include the Plains Indian style war bonnets. Tourists, however, expected Indians to look like the Plains Indians shown in the movies.

Reservation Ceremonies

As a nation which felt obligated to require American Indians to convert to Christianity, the U.S. federal government had outlawed all Indian religions in the nineteenth century and this ban on Indian ceremonie continued until the 1930s. Tourists were fascinated with the pagan American Indian ceremonies, particularly the Hopi Snake Dance. While the Religious Crimes Code had made ceremonies such as the Snake Dance illegal, it was not enforced against the Snake Dance because the Santa Fe Railway promoted it and the tourists demanded to see it.

The Hopi Snake Dance is a 16-day ceremony held in August to help bring the summer rains and a bountiful harvest. It is conducted every other year by the Snake and Antelope clans. Snakes, including poisonous rattlesnakes, are gathered in the fields. They are then carried about the plaza and finally released in the four directions with messages for the spirit world. In their book The Encyclopedia of Native American Religions, Arlene Hirschfelder and Paulette Molin write:

“The functions of the ceremony are broad, related to hunting, war, cure of snakebite, lightning shock (snakes resemble lightning), as well as a plea for rain and crops.”

To encourage tourism into the southwest, the Santa Fe Railway promoted the Hopi Snake Dance as a tourist attraction and in 1900 published a pamphlet on the dance written by a Smithsonian anthropologist, Walter Hough. In the pamphlet, Hough reassured the tourists that while the Hopi continued to perform their Snake dance, they were not dangerous. According to Hough, Indians were living examples of the childhood of man.

In 1917, a news service cameraman defied the Hopi rule against taking motion pictures of the Hopi Snake Dance. He was chased through the desert and his camera is confiscated. After reporting the incident to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, superintendent Leo Crane received the order that no photographs should be permitted. The ban on photography continues today.

Hopi Arts and Crafts

The Hopis are well known for their pottery, basketry, and their carvings of the katsinas (also spelled kachinas). The tourists often purchased Hopi items which were then placed in cabinets of curiosities in homes, offices, and natural history museums. Neither Indians nor non-Indians classified these objects as art, and most non-Indian collectors simply considered them to be examples of Indian crafts. Increased tourism in the early twentieth century had an impact on Hopi arts and crafts.

The Hopis, in response to market demand, began to make traditional items not for tribal use, but for sale to the tourists. As with any entrepreneurial enterprise, the Hopi craftspeople paid attention to what sold and what did not and thus they began to make more of the items which sold well. In addition, non-Indian traders who sold the Hopi crafts in their stores often made suggestions regarding designs, styles, and colors. Thus, the non-Indian tourist stereotypes of what was Indian and what was not began to shape the Indian art market.

The tourist oriented Indian art market resulted in what Christian Feest calls ethnic art. In his book Native Arts of North America, Christian Feest writes:

“Ethnic art was (and is) produced by members of tribal societies primarily for the use of members of other groups, in the case of North America mainly for White Americans. It is generally not thought of as art by its makers, who still live in a social context that does not recognize art as something separate.”

Christian Feest also writes:

“The maker of ethnic art often does not know why his products are bought and what possible use the buyer may make of them. For himself they are first of all a source of income; in the long run they may become an important symbol of the makers’ ethnic identity.”

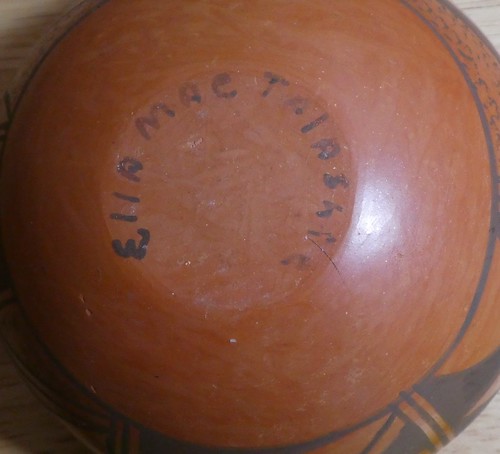

Hopi potters quickly discovered that the tourists did not want large, utilitarian pots such as ollas, but preferred smaller items which were more easily packed in their luggage and displayed in cabinets. As Hopi pottery became popular and began to be considered an art form, tourists wanted the potters to sign their works.

In a similar fashion, the Hopi carvers began to modify their katsina dolls so that they would stand up in a display case (traditionally these carvings were hung). As the carvings began to be considered an art form, there was also pressure for the carvers to sign their works. Traditionally, Hopi artists did not sign their works.

Shown below are some Hopi pots made for the tourist trade. Notice the small size and the signatures. These are from a private collection.

Shown below is a modern action oriented Katsina with signature. This is from a private collection.

Indians 101

Twice each week—on Tuesdays and Thursdays—this series presents American Indian topics. More about the Pueblos from this series:

Indians 101: Pueblo Indian Pottery

Indians 101: Pueblo astronomy

Indians 101: Hopi Political Organization

Indians 101: Pueblo Clowns

Indians 101: Pueblo Weaving

Indians 101: Southwestern Pottery in the Maryhill Museum (Photo Diary)

Indians 101: Acoma Farming

Indians 101: The Hopi Reservation in the 19th century