In 1769 Father Junípero Serra led a group of Franciscan friars from Baja California to establish a series of 21 missions, starting with San Diego de Alcalá in the south. The group was accompanied by a column of Spanish soldiers under the leadership of Captain Gaspar de Portolá. For the Spanish, conversion of American Indians to the “one True Faith, Catholicism” included not only the words of their god, but also the use of military coercion and the threats of total annihilation.

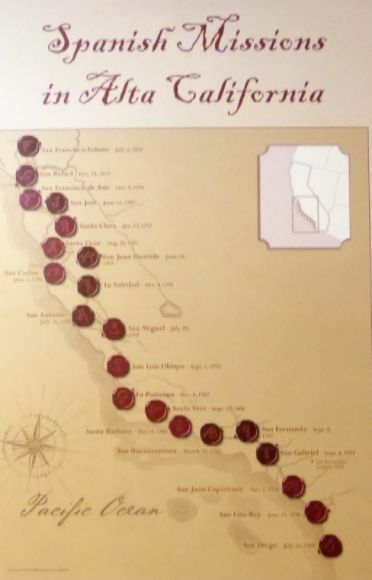

Shown above is a map of the Spanish missions which is on display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California. With one exception, all of the missions were built on the sites of Native American villages.

Shown above is a map of the Spanish missions which is on display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California. With one exception, all of the missions were built on the sites of Native American villages.

Indian people did not come joyously or freely to live and work at the new missions. In his book Where the Lightning Strikes: The Lives of American Indian Sacred Places, Peter Nabokov writes:

“Soldiers snatched Indian families from outlying hamlets to convert them, change their social habits and turn them into an American peasantry.”

The Indian response to the missions was to flee, either in small groups or in large groups

Spain, like other European nations, assumed that non-Christian nations were base and immoral. Thus, the Spanish were obligated to convert the Indians to the one true religion: the Roman Catholic form of Christianity. According to anthropologist Edward Castillo, in a chapter in the Handbook of North American Indians, the Spanish:

“…were steeped in a legacy of religious intolerance and conformity featuring a messianic fanaticism accentuating both Spanish culture in general and Catholicism in particular.”

Spanish intolerance was seen in 1492 when non-Catholics in Spain, primarily Jews and Muslims, were given three choices: (1) to convert to Catholicism, (2) to leave Spain with only the clothes on their backs, or (3) to die. Thousands were killed.

According to Spanish law, the process of converting the Indians to Catholicism was to take ten years and was to involve four stages: (1) misión (mission) which was to include initial contact and the explanation of the importance of God and the King, (2) reducción (reduction) which was to reduce the Indians’ territory by bringing them into a segregated community centered around a church, (3) doctrina (doctrine) in which the Indians would receive instructions on the finer points of Christianity, and (4) curato (curacy) in which the Indians would become tax-paying citizens.

The missionaries, with the help of well-armed soldiers, congregated Indians into fairly large communities. In their book Indians, Franciscans, and Spanish Colonization: The Impact of the Mission System on California Indians Robert Jackson and Edward Castillo report:

“The missionaries, assisted by soldiers, congregated Indians into communities organized along the lines of those in the core areas of Spanish America, where Indian converts were to be indoctrinated in Catholicism and taught European-style agriculture, leatherworking, textile production, and other skills deemed useful by the Spaniards.”

By using Indian labor to produce surplus grain supplies for the Spanish military garrisons, the Franciscan missionaries were able to view Indians as both potential converts and labor. The Franciscan missions are best described as slave plantations in which Indian people were required to work for the Spanish under cruel conditions.

The new living arrangements for the Mission Indians, coupled with the destruction of their aboriginal cultures, had an impact on their health. Death rates were chronically higher than birth rates among the Mission Indians and this meant that for the missions to maintain their Indian workforce they had to continually “recruit” from the outlying tribes.

The death rate among Mission Indian was high enough that it alarmed the Spanish officials. In 1797, the Spanish governor outlined the causes for the high Indian mortality rates in the missions: (1) the heavy workload and poor diet of the Indians living in the missions, (2) the practice of locking women and girls in damp and unsanitary dormitories at night, (3) poor sanitation, and (4) loss of liberty and mobility in the missions.

The governor’s report described the dampness in the dormitories and reported that many did not have even a single blanket to use at night. The use of the dormitories for the women and girls was a form of social control as the missionaries felt that the Indians were promiscuous. Thus, they used the dormitories to protect and control the virtue and virginity of single girls and women. In their chapter in the Handbook of North American Indians, Sherburne F. Cook and Cesare Marino note:

“…the physical confinement and the restriction of social as well as sexual intercourse was completely contrary to native custom and acted as a powerful source of irritation.”

One of the problems of congregation was that it placed large populations in fairly spatially compact communities. This contributed to problems of sanitation and water pollution. It also facilitated the spread of disease.

In the California missions, the new European diseases—smallpox, mumps, measles, malaria— killed many of the Indians who were forced to live there. The Mission Indians also died from respiratory ailments and illnesses caused by poor sanitation. They died from syphilis—introduced to the Indians by the soldiers and the colonists—and by the use of mercury for treating it. The death rate was probably enhanced by the lack of medical attention. According to Robert Jackson and Edward Castillo:

“The general belief held by missionaries that epidemics were a punishment sent by God frequently limited their response to outbreaks.”

The Franciscan missionaries felt that they should not interfere with the will of God. With regard to the lack of response by the Franciscans to the epidemics which devastated the Mission Indians, Robert Jackson, in his book Indian Population Decline: The Missions of Northwestern New Spain, 1687-1840, writes:

“Their ultimate objective was to ensure the Indians’ eternal salvation by their conversion, so there was no moral dilemma as long as the deaths of thousands of converts contributed toward populating heaven. Suffering on earth and receiving the sacraments were necessary for salvation.”

While noting that epidemics, such as measles and smallpox, were devastating to the Mission Indians, Robert Jackson writes:

“However, epidemics do not adequately explain the chronically high mortality rates in the Alta California missions, which were geographically isolated from the rest of New Spain until the early nineteenth century.”

Robert Jackson also reports:

“The climate of coercive social control that existed in the missions engendered a negative psychological response among Indian converts, and contributed to stress which reduced the efficiency of the body’s immunological system.”

Another response to the stress of mission life was for women to have abortions which contributed to the population decline.

For Indian women of childbearing age, the death toll in the California missions was exceptionally high. When the missionaries attempted to destroy native cultures, they also denied young women access to traditional child-care knowledge.

Another cause for the high death rate among Indians who were enslaved in the missions was the unsanitary conditions in which they were forced to live. This was particularly true in the dormitories for the women and girls. While the Spanish understood that there was a correlation between disease and unsanitary living conditions, the missionaries’ concern for social control was stronger than their concerns for sanitation.

Indians 101/201

Twice each week—on Tuesdays and Thursday—this series presents American Indian topics. Indians 201 is an expansion and revision of an earlier essay. More from this series:

Indians 101: The Franciscans in the American Southwest

Indians 101: 17th Century Jesuits in New France

Indians 101: Jesuit Missionaries in Arizona

Indians 101: Spanish Missions Among Florida Indians

Indians 201: Indian Rebellions at the California Missions

Indians 101: Spanish Missionaries in Texas

Indians 101: A very short overview of the California missions

Indians 101: California Missions 200 Years Ago, 1819