Income inequality is not a disease, but rather a symptom of a disease. For over four decades, the United States has suffered from an atrophying of the great American middle class. The decline of post-World War II American economic dominance, the rise of new international competitors, the withering (and the smothering) of trade unions and accelerating globalization with its seamless transnational flow of capital, investment and automated production are among the factors which have choked off the supply of large numbers of good paying jobs for working Americans. If you have any doubt about America's painful transition from a manufacturing powerhouse to a lower-wage service economy, look no further than the top employers in 1955 (GM, U.S. Steel, General Electric, Chrysler and Standard Oil of New Jersey) and now (Walmart, IBM, UPS, Target, Kroger).

Yet for many conservatives, America's record-high level of income inequality is just natural. For the likes of David Brooks, Ari Fleischer, Kathleen Parker, Charles Murray and so many more, the growing chasm between the stratospheric rewards appropriated by a sliver of rich Americans and everyone else left in their dust is a simply a question of values. If only these Americans could overcome their sloth and moral degradation to rediscover the work ethic, traditional marriage and the nuclear family, they could share more of the bounty currently enjoyed by their "more deserving" betters. For the yawning income gap, the angry mobs of the supposed 21st century Kristallnacht have only themselves—or an act of God—to blame. It's no wonder a recent Pew survey found that half of Republicans believe the government should do little (15 percent) or nothing at all (33 percent) to alleviate it.

But income inequality isn't an act of God or the righteous workings of the invisible hand of the market. Much of the upward spiral in incomes of the top 10 percent of Americans since 1980 is the conscious result of three decades of government policy. The dramatic reduction in tax rates for the richest Americans, especially on their capital gains and dividends, has fueled the ever greater concentration of incomes and wealth. But the supply-side snake oil Republicans since Ronald Reagan have spoon-fed Americans did not work its magic: jobs, incomes and GDP grew faster when taxes were higher—even much higher. And while the gilded class has more than made up for its losses during the Great Recession that started in late 2007, workers' wages and incomes have continued to stagnate as American public sector spending at all levels of government contracted. Making matters worse, with Uncle Sam's outlays for non-defense, discretionary spending now at the smallest share of the U.S. economy in 50 years, America is not making the investments in education, R&D, infrastructure and the social safety needed for all Americans to compete and win in the global economy of the 21st century.

For most of the last century, the wages of American workers grew along with the economy's increases in productivity. But as the chart below starkly shows, since 1973 virtually all the gains from rising productivity went into the bank accounts of the richest Americans. "From 1973 to 2011, worker productivity grew 80 percent, while median hourly compensation, after inflation, grew by just one-eighth that amount," the New York Times reported in January, adding, "Since 2000, productivity has risen 23 percent while real hourly pay has essentially stagnated."

Continue reading below the break.

But not for the richest of Americans. It's not just because "the share of wages going to the top 1 percent climbed to 12.9 percent in 2010, from 7.3 percent in 1979." Something else—Ronald Reagan and the GOP's supply-side revolution—happened after 1979. With plummeting tax rates for their salaries and capital gains, the 1 percent began to rapidly pull away from everyone else.

As David Leonhardt documented in April 2012, effective tax rates for most Americans are lower now than in 1960. But for the stratospherically well-to-do, the tax cuts have been mind-boggling. The richest .01 percent saw their overall rate plummet from 71.4 to just 34.2 percent. The top tenth of one percent of American households reaped a windfall as their rates descended from 60 to 33.4 percent. The One Percenters enjoyed a drop from 44 to 30.4 percent. In comparison, those relative proletarians of the top 10 percent of income earners got only modest rate reduction to 27.4 percent from 28 percent. (Only with last year's fiscal cliff deal did the effective tax rate for the 1 percent return to its pre-Reagan level.)

How this all happened is no mystery. It wasn't just the massive Reagan tax cut in 1981 or the Bush tax cuts of 2001 and 2003. It was the dramatic reduction in capital gains tax rates that made the rich much richer and ensured their incomes from investments could grow ever higher. (That development was aided by the explosion in federal tax expenditures, the tax breaks, credits and loopholes which disproportionately aid the itemizing rich while costing Uncle Sam $1.3 trillion a year. It's no wonder Mitt Romney said that income inequality should only be discussed in "quiet rooms.")

In 2011, the Washington Post illustrated the dynamic at work:

As part of the Post's series on the widening chasm between the super-rich and everyone else titled "Breakaway Wealth," the Post concluded that "capital gains tax rates benefiting wealthy feed [the] growing gap between rich and poor." As the Post explained, for the very richest Americans the successive capital gains tax cuts from Presidents Clinton (from 28 to 20 percent) and Bush (from 20 to 15 percent) have been "better than any Christmas gift:"

While it's true that many middle-class Americans own stocks or bonds, they tend to stash them in tax-sheltered retirement accounts, where the capital gains rate does not apply. By contrast, the richest Americans reap huge benefits. Over the past 20 years, more than 80 percent of the capital gains income realized in the United States has gone to 5 percent of the people; about half of all the capital gains have gone to the wealthiest 0.1 percent.

(As University of California economist

Emmanuel Saez showed in February, the rapid recovery and expansion of the stock market since the lows of the Great Recession allowed the top 1 percent to grow their incomes by 11 percent between 2009 and 2011, while the other 99 percent of American people continued to lose ground.)

Reviewing another study by Saez and co-author Thomas Piketty, Ezra Klein explained the central role of low capital gains taxes in "how the ultra-rich are pulling away from the 'merely' rich." As Klein noted, "If you don't look at capital gains, the top 0.01 percent only captures 3.15 percent of income in the United States," adding "that's about a third smaller a share as when capital gains are included." All told, the top 10 percent account for almost half of total income in the United States, up from just over 30 percent in 1970.

The impact of the nation's tax policies on income inequality has hardly been a secret on Capitol Hill. In December 2011, Thomas Hungerford of the Congressional Research Service (CRS) authored an analysis which concluded:

Capital gains and dividends were a larger share of total income in 2006 than in 1996 (especially for high-income taxpayers) and were more unequally distributed in 2006 than in 1996. Changes in capital gains and dividends were the largest contributor to the increase in the overall income inequality. Taxes were less progressive in 2006 than in 1996, and consequently, tax policy also contributed to the increase in income inequality between 1996 and 2006.

Last January, the

CRS' Hungerford published another study which once again confirmed that historically low capital gains tax rates are "by far the largest contributor" to America's historically high income inequality. As

ThinkProgress explained Hungerford's findings, the upward spiral of income inequality (as measured by the Gini coefficient) between 1991 and 2006 is mostly due to federal tax policy that slashed rates on capital gains and dividend income, income which flows almost exclusively to the rich:

By far, the largest contributor to this increase was changes in income from capital gains and dividends. Changes in wages had an equalizing effect over this period as did changes in taxes. Most of the equalizing effect of taxes took place after the 1993 tax hike; most of the equalizing effect, however, was reversed after the 2001 and 2003 Bush-era tax cuts. [...]

The large increase in the contribution of capital gains and dividends to the Gini coefficient, however, is due to the large increase in the share of after-tax income from capital gains and dividends, and to the increase in the correlation of this income source with after-tax income.

Now, these levels of income inequality not seen since the Great Depression might be more tolerable if they served to produce faster economic growth and accelerated job creation. But as Jared Bernstein along with Troy Kravitz and Len Burman of the Urban Institute have shown, lower capitals gains tax rates (contrary to the claims of conservative mythmakers) don't fuel increased investment in the America economy.

As Bernstein demonstrated with the chart above, there's no evidence to support the persistent GOP claim that a low tax rate on capital spurs more investment in the U.S. economy, and thus benefits all Americans. Bernstein found that that the business cycle, not acts of Congress, drives investment in the U.S.

Hard to see anything in the picture supporting the view that either the level or changes in cap gains taxes play a determinant role in investment decisions.

Remember, the ostensible reason for the favoritism in tax treatment here is to incentivize more investment and faster productivity growth. But that's not in the data and the reason it's not in the data is because investors aren't nearly as elastic to cap gains rates as their lobbyists say they are (more precisely, they'll carefully time their realizations to maximize their gains around rate changes, but that's not real economic activity-that's tax planning).

Reviewing other analyses in 2012,

Brad Plumer of the Washington Post concurred with that assessment that low capital gains taxes don't necessarily jump-start investment in the economy:

The top tax rate on investment income has bounced up and down over the past 80 years—from as high as 39.9 percent in 1977 to just 15 percent today—yet investment just appears to grow with the cycle, seemingly unaffected. ...

Meanwhile, Troy Kravitz and Len Burman of the Urban Institute have shown that, over the past 50 years, there's no correlation between the top capital gains tax rate and U.S. economic growth—even if you allow for a lag of up to five years.

Billionaire

Warren Buffett, the inspiration for the "Buffett Rule" advocated by President Obama and his Democratic allies, couldn't agree more. As he told the

New York Times in 2011:

"I have worked with investors for 60 years and I have yet to see anyone—not even when capital gains rates were 39.9 percent in 1976-77—shy away from a sensible investment because of the tax rate on the potential gain. People invest to make money, and potential taxes have never scared them off."

For years, Republicans have similarly claimed that higher marginal income tax rates would scare off the "

job creators" House Speaker John Boehner once described as "the top one percent of wage earners in the United States ... the very people that we expect to reinvest in our economy." If so, those expectations were sadly unmet under George W. Bush. After all, the last time the top tax rate was 39.6 percent during the Clinton administration, the United States enjoyed rising incomes, 23 million new jobs and budget surpluses. Under Bush? Not so much.

That dismal performance prompted the Times' Leonhardt to ask in November 2010, "Why should we believe that extending the Bush tax cuts will provide a big lift to growth?" His answer was unambiguous:

Those tax cuts passed in 2001 amid big promises about what they would do for the economy. What followed? The decade with the slowest average annual growth since World War II. Amazingly, that statement is true even if you forget about the Great Recession and simply look at 2001-7 ...

Is there good evidence the tax cuts persuaded more people to join the work force (because they would be able to keep more of their income)? Not really. The labor-force participation rate fell in the years after 2001 and has never again approached its record in the year 2000.

Is there evidence that the tax cuts led to a lot of entrepreneurship and innovation? Again, no. The rate at which start-up businesses created jobs fell during the past decade.

The data is clear: lower taxes for America's so-called job-creators don't mean either faster economic growth or more jobs for Americans.

The American experience since the Great Depression suggests that high income inequality does not correlate to faster economic growth. But as Jared Bernstein, Ezra Klein and Paul Krugman have been quick to explain, lower income inequality doesn't necessarily "cause" higher GDP. As Brad Plumer summed up a recent paper by Bernstein:

His conclusion: There are compelling reasons to believe that inequality can harm growth, but it's surprisingly difficult to prove this is happening...

In his paper, Bernstein ultimately concludes that there still "is not enough concrete proof to lead objective observers to unequivocally conclude that inequality has held back growth," although he also notes that much of the research is "relatively new" -- and there's a lot more work that could be done.

To be sure, there's a lot to be done—now and in the future—to help working Americans and so reduce the gargantuan income gap. Those policy changes extend far beyond tax reforms to end the hemorrhaging which drains the U.S. Treasury in order to swell the coffers of the richest of the rich.

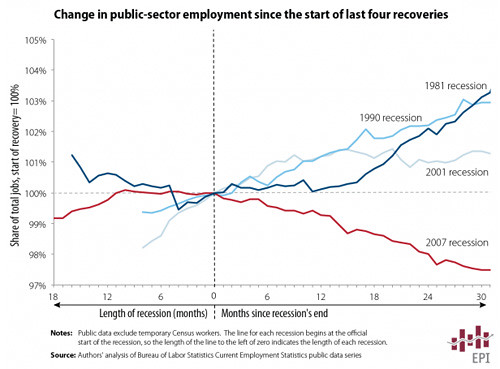

For starters, government at all levels should reverse the contraction of the public sector that has served as the "anti-stimulus" since 2008.

While the Obama stimulus program and minor increases in federal spending since he first took the oath of office boosted employment and economic growth, deep spending cuts by state and local governments more than offset those gains. In May, the Hamilton Project estimated that austerity at the state and local level cost the U.S. economy 2.2 million jobs. In April 2012, the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) explained why:

If public-sector employment had grown since June 2009 by the average amount it grew in the three previous recoveries (2.8 percent) instead of shrinking by 2.5 percent, there would be 1.2 million more public-sector jobs in the U.S. economy today. In addition, these extra public-sector jobs would have helped preserve about 500,000 private-sector jobs.

Counterproductive federal policy hardly ends there. Washington is struggling to extend unemployment benefits for 1.6 million jobless Americans even as the food stamp budget has been cut. The misguided focus on near-term deficit reductions means that Social Security and other federal social insurance programs could see further cuts. As it is,

Dylan Matthews lamented, "The government is the only reason U.S. inequality is so high:"

Pre-tax/transfer inequality in the U.S., as the above chart by the Luxembourg Income Study's Janet Gornick shows, is about equal to that of Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. Finland, Germany, and Britain actually have higher pre-tax/transfer inequality than the U.S. does. The only reason these countries enjoy such low levels of inequality is that their tax and transfer systems reduce inequality much, much more than the U.S. system does.

Looking ahead, the United States must increase its investments in education, infrastructure and research and development to give American companies and their workers the best chance to compete and win in markets around the world. Yet with last year's sequester and the Ryan-Murray budget deal signed by President Obama, the federal government is going backward. As a percentage of the American economy, non-defense discretionary spending (that is, everything outside of defense, Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security and interest on the national debt) is on a downward spiral to the lowest level since the 1950s. (The Paul Ryan House GOP budget supported three years in a row by 95 percent of Congressional Republicans would slash it much further still.)

Ultimately, the gradual implosion of the middle class in today's winner-take-all global environment is putting our economy and democracy at risk. For millions of American families struggling to stay afloat and get ahead, the financial challenge is dire enough. In his controversial new book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, University of Paris economist Thomas Piketty warns that the inevitable concentration of income and wealth is a threat to democracy itself. Alarmist or no, according to one recent study the top .01 percent of American earners provided 40 percent of all political contributions in the 2012 election cycle. And to be sure, their agenda—slashing federal spending, shredding the safety, opposing the minimum wage, undermining unions and deficit reduction above all else—could not be further from the rest of America's. It's no wonder that Pew Research found that fewer Americans believe that hard work leads to success or that they themselves are still members of the middle class.

They can be forgiven for feeling they got the short end of the stick or, perhaps more apt, the invisible finger of the market from the hand of their own government.