Donald Trump may have evaded the Vietnam War because of “bone spurs”, but his uncle played an important role in winning the Second World War.

"Hidden History" is a diary series that explores forgotten and little-known areas of history.

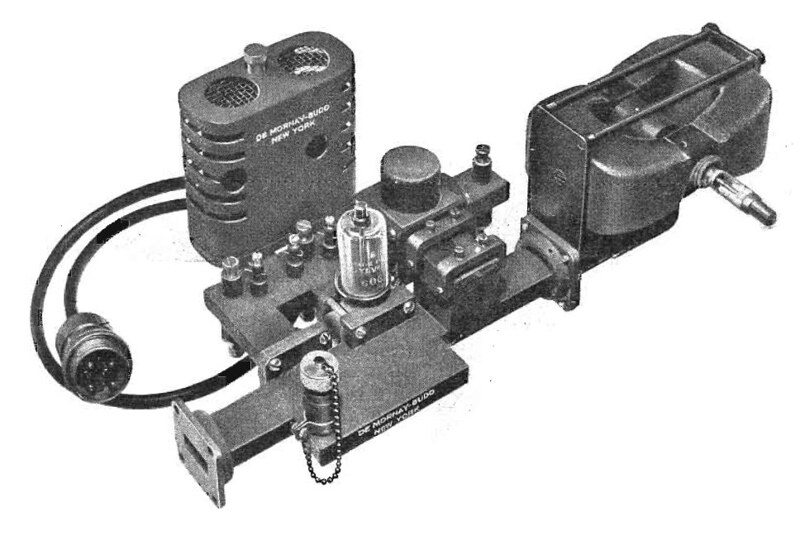

An early magnetron radar photo from WikiCommons

An early magnetron radar photo from WikiCommons

The basic idea behind “radar” was known as early as the 1880s. The Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell had already concluded on theoretical grounds that radio waves, being electromagnetic like light, could possibly be reflected from flat metal objects, and this was demonstrated experimentally in 1888 by the German scientist Heinrich Hertz. By 1904, another German named Christian Hülsmeyer had already patented a device that he called an "obstacle detector” which could be used on board ships to avoid icebergs, rocks or other vessels at a distance. Hülsmeyer approached the navies of several countries with his idea, but none of them were interested. That changed in the 1920s, as combat aircraft and naval guns became more sophisticated and capable. Now, targets could be attacked at long range, and by 1930, research on radar was being carried out, in great secrecy, in the US, UK, Germany, France, USSR, Italy, Holland, and Japan.

In the United States, this work was being done at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington DC. In 1930, the Lab was carrying out experiments with a setup using two separate antennae, one for transmitting and one for receiving, and was able to successfully detect aircraft, but this system was large and cumbersome, which limited its usefulness. Things improved tremendously when the Lab figured out how to incorporate both sending and receiving in the same antenna. That caught the interest of military commanders, and by 1939 the US Navy had deployed a number of crude but effective radar sets to detect incoming aircraft and ships at sea.

The British were also working on radar, and by 1939 they had begun installing a string of radar stations, codenamed “Chain Home”, along the coast with the express purpose of detecting German aircraft as they crossed the English Channel. The Germans, meanwhile, were working on their own radar system, but it was not as capable as the British.

The Blitz, however, demonstrated to the RAF that what they really needed was a radar system that had better resolution and range, could detect and track smaller objects, and, above all, was small and light enough to be carried aloft in an airplane or mounted on small ships like destroyers. This was simply impossible with the vacuum-tube technology of the time.

Then there was a technological breakthrough.

Two British researchers at the University of Birmingham named John Randall and Henry Boot were already working on a device that would become known as the “cavity magnetron”. In simple terms, this worked on much the same principle as blowing across the mouth of an empty bottle to produce a sound—but the magnetron used a beam of electrons instead of air. Just as bottles of different size and shape produce different tones, different arrangements of cavities in the magnetron produced radio waves of different frequencies.

By February 1940, Randall and Boot had produced a prototype radar with a wavelength of just 10 centimeters, giving it much superior resolution, and a few months later they were able to produce power outputs of over a megawatt, giving it superb long range. Best of all, the magnetron’s small size meant it could easily be carried in the bomber and fighter planes of the period.

The British knew that this new radar system would be of enormous importance in the war, but with England under near-daily air attack by the Luftwaffe, Churchill feared that they would never be able to fully develop it. So, he decided to bring the United States and its immense industrial power into the picture. In September 1940, a committee was dispatched to Washington DC to inform the Americans about the top secret British device (even though the US was supposed to be technically “neutral” in the war). The Americans instantly grasped the significance of the discovery, and began immediate efforts to produce the British radar and to improve upon it. And much of this work was centered at MIT.

One of the people involved in this was John G. Trump. The younger brother of real estate mogul Fred Trump (and the uncle of Donald Trump), John had earned a doctorate in electrical engineering and was a professor at MIT. After the British showed up with their magnetron, however, MIT set up a specialized lab for radar research that was known as the “Rad Lab”, and Trump took a position as secretary to the lab’s Director, Alfred Loomis. When in February 1944 the US and UK decided to send a select group of specialists—the “British Branch of the Radiation Laboratory”—to England to coordinate their joint efforts, Trump was sent along as Director.

Within a short time, Trump was applying his technical expertise and his organizational experience to radar research. He was selected by the US Army Air Force to serve on the “Advisory Specialist Group on Radar”, which kept General Carl Spaatz informed about radar developments. Working with the British, Trump and his American team oversaw the development and deployment of virtually every radar and radio-navigation system that was introduced during the war, including radar systems that were used for naval and anti-aircraft gun fire control, night fighter interception, bomber navigation, locating surfaced submarines, and long-range early warning of enemy ships and airplanes. In addition, Trump’s lab was involved in designing counter-measures for German radar systems. Throughout the second half of the war, Allied technological systems were vastly superior to the Germans or Japanese, and they played a decisive role in the defeat of the Axis.

At the end of the war, Trump was appointed to interview and debrief captured and surrendered Nazi radar technicians and operators to learn as much as possible about the German technology. In recognition of his wartime work, Trump was decorated by both the UK and US, receiving the King’s Medal for Service in the Cause of Freedom from King George VI and the President’s Certificate of Merit from Harry Truman. He died in 1985, and was remembered as a genuine war hero.

NOTE: As some of you already know, all of my diaries here are draft chapters for a number of books I am working on. So I welcome any corrections you may have, whether it's typos or places that are unclear or factual errors. I think of y'all as my pre-publication editors and proofreaders. ;)