The mammoth flourished from 16 million years ago until about 11,500 years ago. Sometime between 1.7 million years ago and 1.5 million years ago, the Southern Mammoth (Mammuthus meridionalis) migrated into North America via the Beringian Land Bridge. By about 1 million years ago, the Columbia Mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) had evolved from the Southern Mammoth.

The Columbian Mammoth stood up to 13 feet tall and weighed up to 10 tons. The mammoth grazed on grass. Mammoths had short necks which did not allow their mouths to reach the ground. Like modern elephants, they used their trunks to gather food from the ground and place it in their mouths. It has been estimated that the Columbian mammoth could run 25-35 miles per hour. The mammoth flourished in North America until about 11,500 years ago.

Researchers estimate that a Columbian Mammoth consumed about 770 pounds of food per day (that is about 150,000 calories). Consuming this amount of food would have required grazing for 16 to 18 hours per day. The mammoth also had an inefficient digestive tract which absorbed only about 44% of what the animals ate.

One of the most readily noticeable features of the Columbian Mammoth is the large, greatly curved tusks which can reach up to 13 feet in length. The Columbian Mammoth lived in milder climate zones than the Woolly Mammoths.

Shown above is an artist’s conception of a Columbian mammoth being caught in the Lake Pit at La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, California.

Shown above is an artist’s conception of a Columbian mammoth being caught in the Lake Pit at La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, California.

While this sculpture probably appeals to the human concept of family, in reality the males tended to be solitary while the females lived in herds. Most of the mammoth fossils at La Brea Tar Pits are male, suggesting that males were more likely to get stuck in the goo. It takes just a few inches of goo, by the way, to mire a large animal down.

Shown above is one of the mammoth displays at the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles.

Shown above is one of the mammoth displays at the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles.

A Columbian mammoth skeleton on display at La Brea. The mammoth shown above was about 12 feet tall and weighed about 15,000 pounds.

A Columbian mammoth skeleton on display at La Brea. The mammoth shown above was about 12 feet tall and weighed about 15,000 pounds.

Another view of the La Brea display.

Another view of the La Brea display.

Shown above is the Columbian Mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) Display in the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center in The Dalles, Oregon.

Shown above is the Columbian Mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) Display in the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center in The Dalles, Oregon.

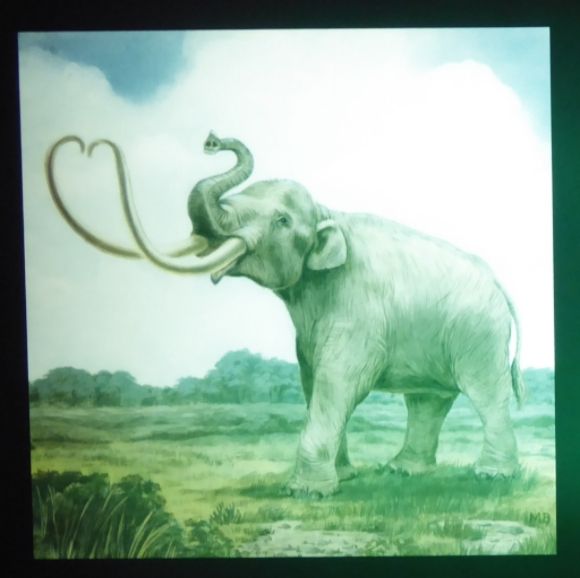

Shown above is an artist’s concept of the Columbia Mammoth in the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center in The Dalles, Oregon.

Shown above is an artist’s concept of the Columbia Mammoth in the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center in The Dalles, Oregon.

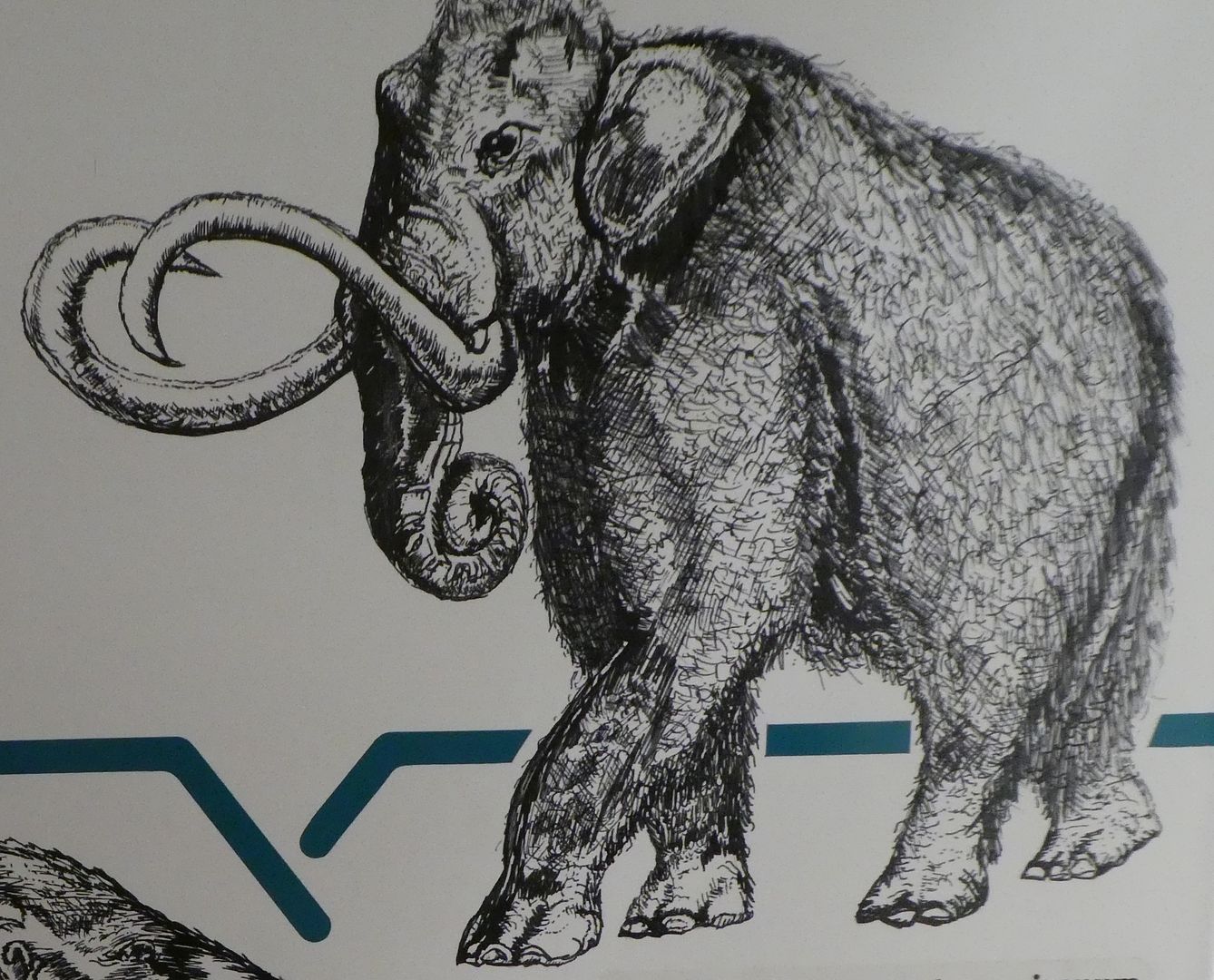

Shown above is an artist’s depiction of Mammuthus primigenius which stood 10 to 12 feet high at the shoulder. This is on display in the Wenatchee Valley Museum in Wenatchee, Washington.

Shown above is an artist’s depiction of Mammuthus primigenius which stood 10 to 12 feet high at the shoulder. This is on display in the Wenatchee Valley Museum in Wenatchee, Washington.

This display of mammoth fossils is in the Wenatchee Valley Museum in Wenatchee, Washington.

This display of mammoth fossils is in the Wenatchee Valley Museum in Wenatchee, Washington.

Shown above is a mammoth jaw which is on display in the Wenatchee Valley Museum in Wenatchee, Washington.

Shown above is a mammoth jaw which is on display in the Wenatchee Valley Museum in Wenatchee, Washington.

American Indians and Mammoths

In 1932, archaeologists working in a site near Clovis, New Mexico, found an ancient stone spearpoint embedded in the rib of a mammoth, thus starting the hypothesis of the Clovis mammoth hunters as the first Americans.

Clovis hunters understood that large mammals, such as the mammoth, had to have water and thus they could be found at watering holes and ponds. Furthermore, they understood that the soft ground near the watering holes could slow the animals down and would sometimes entrap the large mammals. At a Clovis mammoth kill site in Wyoming, it appears that the hunters drove a mammoth into the muck of the waterhole and then dispatched it as it had limited mobility. In a 1962 report in National Geographic, archaeologists Cynthia Irwin, Henry Irwin, and George Agogino report:

“To them the mammoth was a windfall, a veritable mountain of meat. It meant the difference between mere survival and plenty for weeks, perhaps even months.”

At the Colby site near Worland, Wyoming, Clovis hunters 12,000 years ago killed several mammoths in a shallow arroyo. The hunt probably took place in the later fall or early winter. The hunters partly butchered the animals, then stacked the carcasses into piles to be frozen. The hunters then moved on, returning to open the cache when they needed meat. In other words, Clovis hunters understood the basic principles of freezing and used frozen meat caches.

At the site of Tultepec, north of Mexico City, archaeologists have uncovered two large pits—each about 80 feet in diameter and about 6 feet deep—that appear to have been used in hunting mammoths. The pits contained 824 mammoth bones from 14 different animals. Hunters, 15,000 years ago, would drive mammoths into the pits using torches. Once trapped in the pits, the confused animals could then be more easily killed and butchered.

The extinction of the mammoths in North America seems to correspond with the flourishing of Clovis technology and this led to the hypothesis that overhunting contributed to the extinction. However, the archaeological data from the many Clovis sites which have been studied in North America doesn’t really substantiate the idea of Clovis hunters focusing on mammoths: there are only a dozen sites in which Clovis is associated with mammoth remains. While the over-hunting hypothesis is popular, the archaeological data doesn’t support it.

More Ancient America

Ancient America: Mastodons

Ancient America: North American Camels

Ancient America: Bears

Ancient America: The prehistoric Southwest, 1375-1425 CE

Ancient America: Some Plateau Indian petroglyphs (museum tour)

Ancient America: Northeast Arizona, 560 BCE to 825 CE

Ancient America: A very short overview of the prehistory of the Grand Canyon

Ancient America: A very short overview of Clovis