Mastodons originally evolved in Africa about 20 million years ago and later spread into Europe and Asia. With the Bering Land Bridge that once connected Asia and North America, mastodons migrated into North America about 17 million years ago. During the Pleistocene, it ranged from Alaska to Florida. The American Mastodon (Mammut americanum) became extinct about 8,000 years ago.

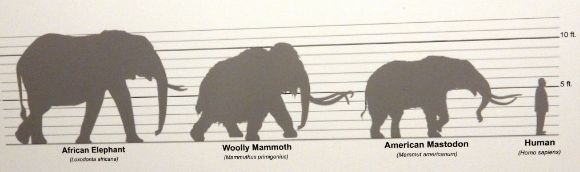

The illustration above compares the size of humans, the American Mastodon, the Wooly Mammoth, and the African Elephant. This is from a display in the Museum and Arts Center in Sequim, Washington.

The illustration above compares the size of humans, the American Mastodon, the Wooly Mammoth, and the African Elephant. This is from a display in the Museum and Arts Center in Sequim, Washington.

The American Mastodon generally inhabited forests or woodlands characterized by spruce and evergreen trees.

Shown above is the mastodon display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California.

Shown above is the mastodon display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California.

According to the San Bernardino County Museum display:

“Adult mastodons were too large to have natural predators, although calves would have been meals for giant cave bears and other large carnivores. But once humans arrived on the scene, mastodons were hunted for food.”

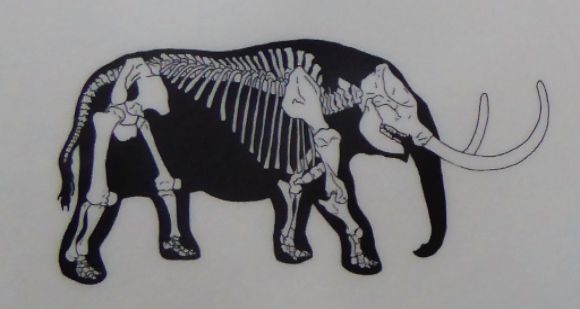

Shown above is the Mastodon display in the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

Shown above is the Mastodon display in the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

Shown above is another view of the Mastodon skeleton in the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

Shown above is another view of the Mastodon skeleton in the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

Shown above is another view of the Mastodon skeleton in the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

Shown above is another view of the Mastodon skeleton in the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

Shown above is more from the Mastodon display in the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History

Shown above is more from the Mastodon display in the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History

Shown above is the Conway Mastodon displayed in the Ohio History Center in Columbus, Ohio. The Conway Mastodon was discovered in 1887

Shown above is the Conway Mastodon displayed in the Ohio History Center in Columbus, Ohio. The Conway Mastodon was discovered in 1887

According to the Ohio History Center display:

“When living, this male individual stood more than 10 feet tall at the shoulder. At the time of death it was probably in its late 20s or early 30s.”

Shown above is one of the Conway Mastodon tusks. Each tusk is 9.5 feet long and weights more than 100 pounds.

Shown above is one of the Conway Mastodon tusks. Each tusk is 9.5 feet long and weights more than 100 pounds.

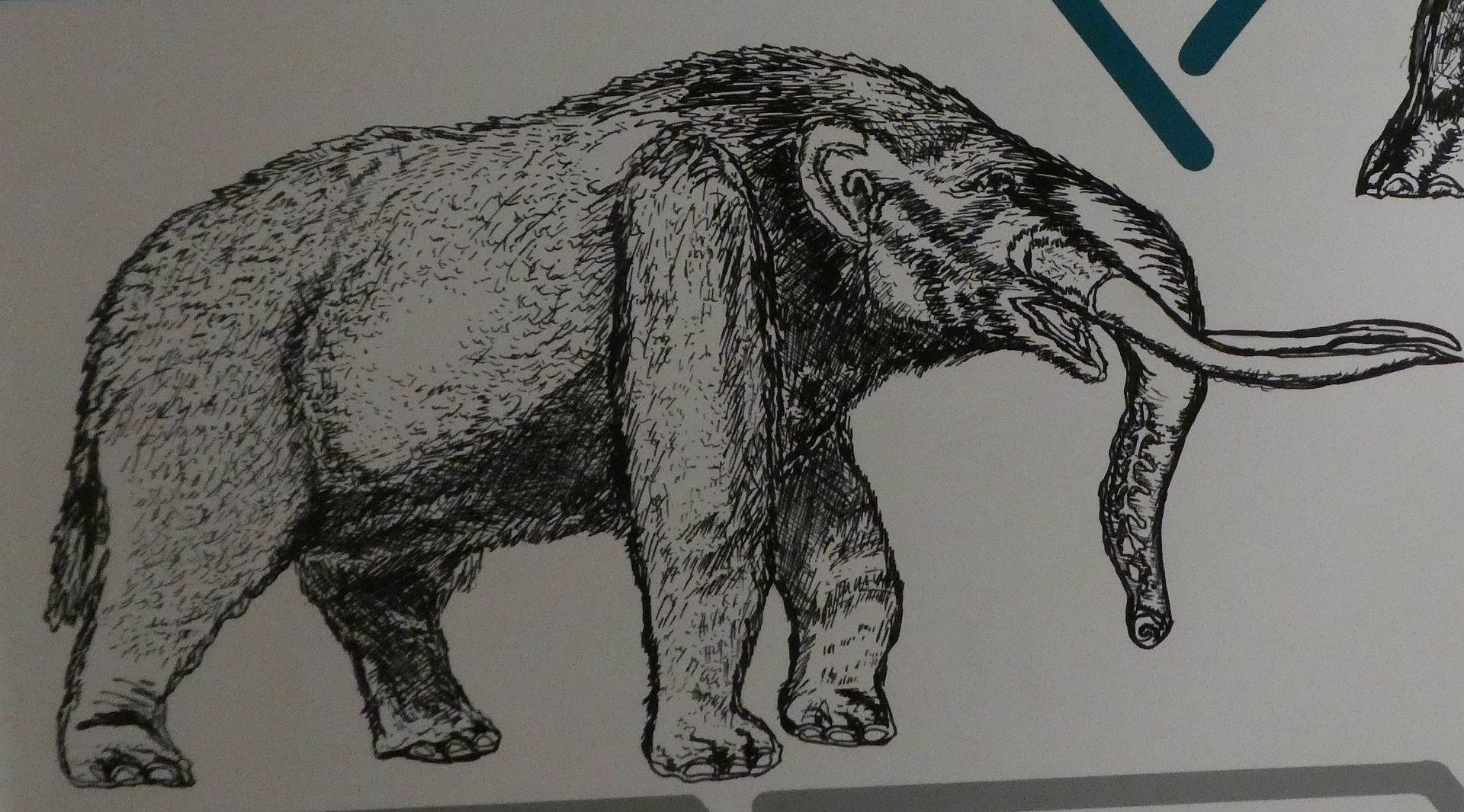

Shown above is an artist’s depiction of Mammut americanus which stood 8 to 9 feet high at the shoulder. This is on display in the Wenatchee Valley Museum in Wenatchee, Washington.

Shown above is an artist’s depiction of Mammut americanus which stood 8 to 9 feet high at the shoulder. This is on display in the Wenatchee Valley Museum in Wenatchee, Washington.

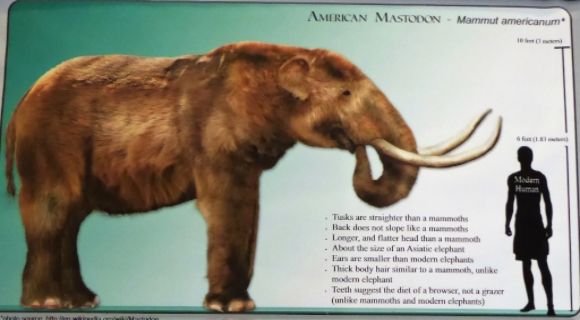

Shown above is the mastodon display in the La Brea Tar Pits Museum in Los Angeles, California.

Shown above is the mastodon display in the La Brea Tar Pits Museum in Los Angeles, California.

A mastodon is different from mammoths and from other elephants in that it has a smaller size and simple, low-crowned teeth. In looking at the differences between mastodons and mammoths, Ian Lange, in his book Ice Age Mammals of North America: A Guide to the Big, the Hairy, and the Bizarre, reports:

“While individual teeth of mastodons have cone-shaped grinding surfaces, the eating surfaces of mammoth teeth are formed of ridges, like those of modern elephants. Mammoth skulls were domed while mastodon skulls were low-browed. And while mammoths were considerably taller, mastodons had proportionally longer and more massive bodies.”

Shown above are the teeth of a mastodon in the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry display in Portland, Oregon.

Shown above are the teeth of a mastodon in the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry display in Portland, Oregon.

Shown above is an illustration of the mastodon on display in the Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument in Hagerman, Idaho.

Shown above is an illustration of the mastodon on display in the Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument in Hagerman, Idaho.

Mastodons and American Indians

About 11,800 BCE, an elderly mastodon which had survived an encounter with an Indian hunter earlier in its life, waded into a small pond near present-day Sequim, Washington where it fell over and died of old age. Indian scavengers quickly butchered the portion of the body which remained above the water, undoubtedly feasting upon mastodon roasts and steaks for several days.

Shown above is a diorama in the Museum and Arts Center in Sequim, Washington showing the butchering of the Manis Mastodon.

Shown above is a diorama in the Museum and Arts Center in Sequim, Washington showing the butchering of the Manis Mastodon.

Shown above is the full-size depiction of the Manis Mastodon with bones found by archaeologists in place.

Shown above is the full-size depiction of the Manis Mastodon with bones found by archaeologists in place.

Shown above are the mastodon tusks from the Manis Site. These are not on display but are kept in a tank of water to preserve them.

Shown above are the mastodon tusks from the Manis Site. These are not on display but are kept in a tank of water to preserve them.

At the Manis Site, the mastodon had the tip of a bone point about the size of a human thumb embedded in a rib—an indication that it had encountered a hunter and had escaped. In their book Archaeology in Washington, Ruth Kirk and Richard Daugherty report:

“The spear had been thrust some time before the animal died; the wound had not been fatal.”

The bone point had been made from a mastodon bone.

At the time the Manis mastodon was butchered, the main mass of the ice field had drawn back to today’s San Juan Islands near the state of Washington. People at the pond where the mastodon had died could still see remnants of the continental glacier.

In New Mexico, archaeologists at Sandia Cave find evidence that early Indians, often called Paleoindians by some, are utilizing mammoth, mastodon, giant llama, ground sloth, and Bison antiquus. Humans occupied the cave only infrequently for brief periods of time.

In Florida, Indians left some stone tools and a mastodon tusk at the Page-Ladson site. These are dated to about 12,800 BCE. There is also some evidence of dogs at the site. In his book Human From the Beginning, Christopher Seddon writes:

“The tusk bears deep grooves, apparently made as it was removed from its socket.”

In Kentucky, at Big Bone Lick site, dated to about 10,000 BCE, archaeologists found mastodon bones as well as Clovis fluted bifaces.

In Missouri, Indian people at the Kimmswick site killed a mastodon. The environment at this site at that time, 9000 BCE, was deciduous woodland with open grassy areas.

In New York, Indian hunters using Clovis technology were hunting mastodons at the Hiscock site at about 8790 BCE.

At the Icehouse Bottom site in Tennessee, dated to about 8000 BCE, Indian people were gathering walnuts and butternuts and were hunting mastodon.

More Ancient America

Ancient America: Mammoths

Ancient America: The Pleistocene Extinctions

Ancient America: North American Camels

Ancient America: Avonlea, the early bow hunters

Ancient America: Aboriginal Mining

Ancient America: Columbia River Rock Art (Photo Diary)

Ancient America: A very short overview of the prehistory of the Grand Canyon

Ancient America: How Old is It?